Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Center for Austrian Studies

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Center for Austrian Studies

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Center for Austrian Studies

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

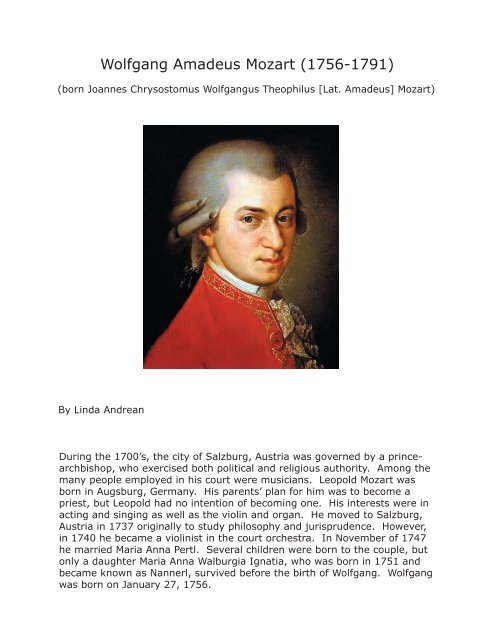

<strong>Wolfgang</strong> <strong>Amadeus</strong> <strong>Mozart</strong> (<strong>1756</strong>-<strong>1791</strong>)<br />

(born Joannes Chrysostomus <strong>Wolfgang</strong>us Theophilus [Lat. <strong>Amadeus</strong>] <strong>Mozart</strong>)<br />

By Linda Andrean<br />

During the 1700’s, the city of Salzburg, Austria was governed by a princearchbishop,<br />

who exercised both political and religious authority. Among the<br />

many people employed in his court were musicians. Leopold <strong>Mozart</strong> was<br />

born in Augsburg, Germany. His parents’ plan <strong>for</strong> him was to become a<br />

priest, but Leopold had no intention of becoming one. His interests were in<br />

acting and singing as well as the violin and organ. He moved to Salzburg,<br />

Austria in 1737 originally to study philosophy and jurisprudence. However,<br />

in 1740 he became a violinist in the court orchestra. In November of 1747<br />

he married Maria Anna Pertl. Several children were born to the couple, but<br />

only a daughter Maria Anna Walburgia Ignatia, who was born in 1751 and<br />

became known as Nannerl, survived be<strong>for</strong>e the birth of <strong>Wolfgang</strong>. <strong>Wolfgang</strong><br />

was born on January 27, <strong>1756</strong>.

Leopold <strong>Mozart</strong> about 1765.<br />

Portrait attributed to Peitro Antonio Lorenzoni<br />

<strong>Wolfgang</strong> and Nannerl were extremely gifted musically as children. Nannerl<br />

began music lessons on the clavier (an early piano) at the age of seven.<br />

<strong>Wolfgang</strong>, aged three, would spend hours picking out tunes, so by the age<br />

of four, their father began teaching <strong>Wolfgang</strong> minuets. He learned them<br />

very easily and by the age of five, began composing his own music, which<br />

he would play to his father who then wrote the music down. <strong>Wolfgang</strong>’s first<br />

appearance as a child prodigy was playing the clavier at the age of five in an<br />

appearance with his sister be<strong>for</strong>e the court at Munich.<br />

Records of the early tours of the <strong>Mozart</strong> family are to be found in letters Leopold<br />

wrote to Lorenz Hagenauer, the family friend and landlord of the <strong>Mozart</strong><br />

home. Hagenauer was most likely the person who financed the early travels<br />

of the <strong>Mozart</strong> family. In September, 1762 the <strong>Mozart</strong> family set out <strong>for</strong> Vienna<br />

to per<strong>for</strong>m, and did not return home until January 1763. As young <strong>Wolfgang</strong><br />

was per<strong>for</strong>ming be<strong>for</strong>e the royalty of Europe, he was losing his baby<br />

teeth!<br />

In her reminiscences, Nannerl summed up the first part of their<br />

tour: “Munich, Augsburg, Ulm, Ludwigsburg, Bruchsal, Schwetzingen,<br />

Heidelberg, Mannheim, Worms, Mainz, Frankfurt on Main,<br />

Mainz, Coblenz, Bonn, Brühl, Cologne, Aix-la-Chapelle, Liège, Tillemonde,<br />

Louvain, Brussels, Mons, Paris, where they arrived on<br />

the 18th November 1763.”<br />

From http://www.mozartproject.org/biography/bi_61_65.html

<strong>Wolfgang</strong> probably painted by Pietro<br />

Antonio Lorenzoni, 1763.<br />

The beautiful outfi t was a gift from the<br />

Empress Maria Theresa<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> as a child was greatly adored at the<br />

<strong>Austrian</strong> court of Empress Maria Teresa.<br />

1763 one of the fi rst major concert tours <strong>for</strong> <strong>Mozart</strong> to the courts of Europe.

Illustration by Elaine<br />

Bonabel in Mörike, p. 119<br />

depicting a typical trip by<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong>.<br />

The family most often rented<br />

a coach, but on occasion<br />

either purchased one or<br />

were lent a coach to use.<br />

The horses were rented <strong>for</strong><br />

use <strong>for</strong> a certain number<br />

of miles and would then be<br />

exchanged <strong>for</strong> fresh horses<br />

at the next Inn stop.<br />

The roads were rough and<br />

the springs in the coaches<br />

not very com<strong>for</strong>table <strong>for</strong><br />

long distance travel. Note<br />

the springs on the coach in<br />

the drawing.<br />

On Christmas Eve, 1763, the <strong>Mozart</strong>s were invited to the French court of Queen<br />

Maria Leszczynska and Louis XV <strong>for</strong> two weeks. On New Years Day the <strong>Mozart</strong><br />

family was invited to the court dinner with the royal couple. The family stood behind<br />

the royal couple during the meal. Leopold described the experience:<br />

“My <strong>Wolfgang</strong> was graciously privileged to stand beside the Queen the<br />

whole time, to talk constantly to her, entertain her and kiss her hands<br />

repeatedly, besides partaking of the dishes which she handed him from the<br />

table,” . . . “I stood beside him, and on the other side of the King . . . stood<br />

my wife and daughter.”<br />

(www.mozartproject.org/biography/bi_61_65.html)

For the next several years, family life consisted of traveling. The purpose of these<br />

trips was to show off the musical abilities of the two extraordinary children. During<br />

the trips to Paris, the most important musical center in Europe, then to England,<br />

Germany, and Italy young <strong>Wolfgang</strong> met many famous musicians and learned a<br />

great deal from them. He began to compose music seriously, so that by the time<br />

he was nine years old in 1765, his fi rst sonatas were being published in Paris.<br />

During these intense early travels <strong>Wolfgang</strong> also contracted several serious illnesses:<br />

strep throat, rheumatoid arthritis and typhoid fever, from which he nearly<br />

died.<br />

Between 1763 and 1765 during his travels, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> composed:<br />

2 sonatas while in Paris<br />

7 sonatas while in London as well as two symphonies,<br />

2 arias, a motet (a choral composition) and several<br />

untitled pieces<br />

and while in The Hague, an aria and a symphony.<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> was defi nitely a unique child!<br />

Estimated distances<br />

between<br />

cities:<br />

Vienna to<br />

Amsterdam=<br />

938 km/538 mi.<br />

Paris=1,037 km<br />

/645 mi.<br />

London =1,237<br />

km/668 mi.

Leopold <strong>Mozart</strong> and his children<br />

L. C. de Carmontelle watercolor, 1763-64<br />

<strong>Wolfgang</strong> Hildesheimer describes the early works as composed<br />

“with an originality of melody and modulation which goes beyond<br />

the routine methods of this contemporaries.” (pp. 34-5) <strong>Mozart</strong> at<br />

this young age possessed the ability to vary the moods of the music<br />

within the conventional <strong>for</strong>ms of the period. <strong>Mozart</strong> later wrote to<br />

his father that music must not offend the ear but must please those<br />

listening.<br />

On the return to Salzburg in 1769, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> composed masses <strong>for</strong><br />

the cathedral of the prince-archbishop. An important tradition in<br />

Salzburg was the custom of the graduating students at the Benedictine<br />

University to celebrate the end of the academic year with a<br />

serenade called “Finalmusik”, which was composed <strong>for</strong> a march or<br />

procession of the students. The march would be commissioned by<br />

the students or their families in honor of the graduation. <strong>Wolfgang</strong><br />

composed several such marches.

By the end of 1769, father and son<br />

were off to Italy <strong>for</strong> new composing<br />

opportunities and exposure to new<br />

audiences. <strong>Wolfgang</strong> was now composing<br />

symphonies, sonatas, concertos,<br />

operas and arias. The life of the<br />

young <strong>Mozart</strong> was one of travel, composing<br />

and per<strong>for</strong>ming. Returning to<br />

Salzburg in 1772, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> received a<br />

<strong>for</strong>mal court position as the Konzertmeister,<br />

which meant he now received<br />

a salary. He was also busy composing<br />

<strong>for</strong> many private patrons, which<br />

was an important source of income<br />

<strong>for</strong> musicians and composers. The<br />

composer Franz Josef Haydn was an<br />

important influence on his work during<br />

this period, especially in writing<br />

string quartets. During this period,<br />

<strong>Wolfgang</strong> wrote his first true keyboard<br />

concerto (K.175 in D), which was<br />

among the few of his keyboard concertos<br />

to be published in his lifetime.<br />

While in Salzburg, he was busy composing<br />

sacred music.<br />

In 1774, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> was invited to compose an opera buffa (comic opera) <strong>for</strong> the<br />

Munich opera season. The opera was La finta giardiniera (the feigned garden-girl).<br />

Operas were written specifically <strong>for</strong> the singers who were to per<strong>for</strong>m them, which<br />

meant the composer had to work closely with the per<strong>for</strong>mers and understand the<br />

ability of each singer. During his stay in Munich, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> was also busy writing<br />

sonatas. The most popular sonata was K.283 in G because of its workmanship,<br />

sequence of ideas, phrase repetitions and ingenious tonal balance (Sadie, p. 369).<br />

With the sonatas, Stanley Sadie points out, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> developed from composing<br />

conventional music to works of much greater individuality. Returning to Salzburg<br />

in March 1775, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> turned to composing concertos along with serenades of<br />

the Finalmusik type. He was to continue working in Salzburg until 1777 in his position<br />

as Konzertmeister on an annual salary of 150 gulden.<br />

In August of 1777, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> received permission from the Salzburg prince-archbishop<br />

Colloredo to be released from his appointment. Leopold had to remain at<br />

court, so it was <strong>Wolfgang</strong>’s mother who traveled with him now to the courts of<br />

southern and western Germany seeking an appointment hopefully in Mannheim or<br />

Munich. As in the <strong>for</strong>mer travels, the <strong>Mozart</strong>s traveled by horse-drawn coaches,<br />

which they would have either bought or rented. Horses would be hired at various<br />

inns along the way. The route Leopold carefully planned <strong>for</strong> mother and son to

take would bring them in contact with friends along the way whom Leopold<br />

thought would be most helpful. This was <strong>Wolfgang</strong>’s first venture into the<br />

world without his father. Maria was following her husband’s instructions but<br />

did not make the same demands on <strong>Wolfgang</strong> as her husband would have.<br />

Thus <strong>for</strong> the first time in his life, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> had more of a role in the decisions<br />

of what he wanted to do. He had a new sense of independence. From the<br />

correspondence between the family members, it is clear Leopold did not appreciate<br />

his son’s decisions.<br />

<strong>Wolfgang</strong> and his mother traveled first to Mannheim where they stayed <strong>for</strong><br />

several months. Then it was on to Paris. <strong>Wolfgang</strong> was not professionally<br />

successful in Paris. Tragedy also struck when his mother died there on June<br />

30, 1778. <strong>Wolfgang</strong> had acquired a large amount of debt and finally had to<br />

leave Paris <strong>for</strong> home.<br />

It was during the stay in Mannheim in 1777<br />

that <strong>Mozart</strong> found his first romantic inspiration<br />

in the person of Aloysia Weber. In<br />

Mannheim, <strong>Mozart</strong> was directed to her father<br />

who would be able to copy music <strong>for</strong> him.<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> took Aloysia on as a voice pupil and<br />

cultivated her voice. She inspired him to<br />

write music <strong>for</strong> her to per<strong>for</strong>m. They remained<br />

friends following her marriage and<br />

over the years, <strong>Mozart</strong> continued to write<br />

several arias <strong>for</strong> her. As a very famous opera<br />

singer in Vienna, she per<strong>for</strong>med the roles<br />

of Donna Anna in Don Giovanni in the premiere<br />

in 1778 and the role of Constanze in a<br />

revival production of The Abduction from the<br />

Aloysia Weber<br />

Seraglio.<br />

Anna Nancy Storace<br />

The other woman who inspired him to write music<br />

<strong>for</strong> her was Anna Storace (known as Nancy), one<br />

of the most famous singers throughout Europe of<br />

the period. For Anna, he composed the role of<br />

Susanna in Le Nozze di Figaro, which premiered<br />

at the Burgtheater in Vienna on May 1, 1786 and<br />

the role of Zerlina in Don Giovanni. A third piece<br />

he composed <strong>for</strong> her as a farewell gift be<strong>for</strong>e she<br />

left Vienna to go to London in 1787, was the aria,<br />

“Ch’ io mi scordi di te?... Non temer amato bene,”<br />

K505, a piece <strong>for</strong> voice and piano. They per<strong>for</strong>med<br />

the piece together at her farewell concert at the<br />

Kärntnertor Theater. The works <strong>for</strong> Anna are considered<br />

to be among <strong>Mozart</strong>’s greatest <strong>for</strong> voice.

The year 1779 saw <strong>Wolfgang</strong> back in Salzburg with a court appointment once<br />

again. The next few years were very productive <strong>for</strong> him as he composed<br />

many religious and secular bodies of work. Late in 1777 he had begun composing<br />

an opera that was to have been <strong>for</strong> the Mannheim court. The opera<br />

developed into Idomeneo (an opera seria) and was presented first in Munich<br />

in January, 1781. In this opera, <strong>Mozart</strong> created a powerful and emotional<br />

work in which he expanded creatively beyond his previous works as well as<br />

beyond the typical operas of the period. Idomeneo takes place on the island<br />

of Crete following the Trojan War, focusing on a promise made to Neptune by<br />

Idomeneo, the king of Crete, and the intrigue based on the promise and the<br />

relationships involved.<br />

Thinking that he would never be able to do the work he wanted to do in Salzburg,<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> moved to Vienna in 1781. He initially stayed at the Teutonic<br />

Order lodge house, which housed the employees of his Salzburg employer,<br />

Archbishop Colloredo. After a few months he found lodging at the house of<br />

his friends from Mannheim, the Webers, who had followed their daughter<br />

Aloysia to Vienna. Aloysia meanwhile had married. It was a younger daughter<br />

who then caught his attention, Constanze (called Stanzi) who <strong>Mozart</strong><br />

married in August, 1782. <strong>Mozart</strong>’s father and sister were opposed to the<br />

marriage because they thought Constanze to be beneath them socially and<br />

as a result, they never developed a good relationship with Constanze.<br />

An artist’s<br />

rendering<br />

of <strong>Wolfgang</strong><br />

and Constance<br />

on<br />

their honeymoon.<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> and Constanze had six children over their nine years of marriage.<br />

Only two of the children survived beyond childhood, Karl Thomas, born in<br />

1784, and Franz Xaver <strong>Wolfgang</strong>, born in <strong>1791</strong>, was four months old when<br />

his father died.

Franz and Karl<br />

Constanze, portrait by Lange, 1782<br />

Constanze was particularly fond of fugues, and <strong>Mozart</strong> composed several <strong>for</strong><br />

her. <strong>Mozart</strong> wrote to his sister Nannerl in April 1782:<br />

“Well, as she has often heard me play fugues out of my head, she<br />

asked me if I had ever written any down, and when I said I had not,<br />

she scolded me roundly <strong>for</strong> not recording some of my compositions in<br />

this most artistically beautiful of all musical <strong>for</strong>ms and never ceased to<br />

to entreat me until I wrote down a fugue <strong>for</strong> her.”<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> in Vienna<br />

The citizens of Vienna did not hold the same regard <strong>for</strong> <strong>Mozart</strong> as an adult<br />

as was shown to him as a child. As an adult, he was one of several successful<br />

musicians and composers and no longer had the special status of child<br />

prodigy. His mature musical style was not that which the Viennese were<br />

used to and had established a taste <strong>for</strong>. Life became more of a struggle <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> because he never received the court appointment he wanted. However,<br />

that did not slow him down. He continued to be a prolific composer<br />

and to explore new approaches in his works. It was with the collaboration<br />

of the librettist (a poet and playwright, the person who writes the text of the<br />

opera) Lorenzo da Ponte that he composed his three great operas during his<br />

years in Vienna, Le Nozze di Figaro (1786); Don Giovanni (1787); and Così<br />

fan tutte (1790).

Lorenzo da Ponte<br />

The oldest known surviving playbills <strong>for</strong> Don Giovanni and Cossi fan tutte

19th century anonymous watercolor of The Marriage of Figaro<br />

Playbill from 1786<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> was at the peak of his creativity and with da Ponte, was able to exploit<br />

his full potential. In the operas, Hildesheimer states, <strong>Mozart</strong> conveyed<br />

the impression of “an absolutely conscious creative power, as if <strong>Mozart</strong> had<br />

asked himself how much of human affairs and feelings, actions and longings,<br />

he could bring to the material at hand, which was bound to be meager compared<br />

to his own artistic dimensions. He increasingly ignored the prescribed<br />

external standards.” (p. 145) His later works convey a tremendous range<br />

of characters and emotional experiences, with music that directs the action<br />

rather than following it. <strong>Mozart</strong> created full ranges of emotion with his music.<br />

The use of major and minor keys gives the impression of opposite reactions<br />

and feelings. <strong>Mozart</strong> was constantly experimenting and testing combinations<br />

outside the popular standards of the period. He was innovative.<br />

Many comments and opinions have been written about <strong>Mozart</strong>’s personal life,<br />

especially the years in Vienna. To understand <strong>Mozart</strong> better it is helpful to<br />

look at him in the context of his times and there<strong>for</strong>e, it is helpful to understand<br />

what life was like in the Vienna of the 1780’s. Vienna is portrayed as a<br />

city loving music and entertainment of all sorts. With the availability of exceptionally<br />

talented architects, the nobility had created architecturally beautiful<br />

buildings and gardens. As a re<strong>for</strong>mer, Emperor Joseph II wanted

the people to enjoy the gardens. In 1775 he opened the imperial garden,<br />

the Augarten, as well as his hunting grounds, the Prater, to the public, so<br />

that on Sundays the gardens were the gathering place <strong>for</strong> all ranks of society.<br />

Joseph himself walked freely among the strollers in the parks. Free<br />

concerts were per<strong>for</strong>med. People enjoyed coffee and pastries at the cafes.<br />

Originally special theaters were built by the nobility as court theaters in the<br />

early 18th century. Soon popular theaters were built in the public squares.<br />

Then came the large public popular theaters. The Käntnertor was built in<br />

1708. Joseph II developed the Burgtheater in an ef<strong>for</strong>t to bring the many<br />

different people of his empire together through cultural per<strong>for</strong>mances, including<br />

everything from opera to jugglers. When Emmanuel Schikaneder,<br />

known <strong>for</strong> his collaboration with <strong>Mozart</strong> on The Magic Flute, came to Vienna,<br />

he saw the need <strong>for</strong> establishing a theater that would be able to utilize set<br />

machinery and large groups on a stage large enough to create his remarkable<br />

productions. It was at the Theater an der Wien that The Magic Flute<br />

was first per<strong>for</strong>med. Per<strong>for</strong>mers such as Johann Nestroy and Ferdinand Raimund<br />

became famous and adored by their public because of their remarkable<br />

abilities to per<strong>for</strong>m in various roles.<br />

Kärntnertor Theater

Joseph II felt that revolution should come from above. Part of his version of<br />

revolution was to encourage the development of the many Freemason lodges<br />

in the city. The lodges and their new ways of viewing society appealed to<br />

the prominent thinkers and activists of the period. Joseph II and <strong>Mozart</strong><br />

belonged to lodges. <strong>Mozart</strong>’s Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte) first per<strong>for</strong>med in<br />

<strong>1791</strong>, is often called the “Masonic Opera” because of its embodiment of the<br />

Masonic beliefs. The librettist, Emanuel Schikaneder, and <strong>Mozart</strong> were members<br />

of the same lodge. Several sources write that in composing “The Magic<br />

Flute”, <strong>Mozart</strong> and Schikaneder, were attempting to demonstrate to the public<br />

that the Freemasons, as seen through the Sun Priests, held reason, truth<br />

and virtue in the greatest esteem.<br />

Drawing by Gottfried<br />

Engelmann <strong>for</strong><br />

Monsieur Garcia’s<br />

costume in the<br />

production of Don<br />

Giovanni<br />

Leopold Schikaneder played the role of Papageno, the<br />

bird catcher, in The Magic Flute.<br />

There were several venues in which <strong>Mozart</strong> per<strong>for</strong>med and in which his works<br />

were per<strong>for</strong>med. In 1782, <strong>Mozart</strong> and other musicians were required on<br />

Sunday afternoons to appear in the home of his patron Gottfried van Swieten<br />

to per<strong>for</strong>m the music of Bach, Handel and Haydn. <strong>Mozart</strong> and several friends<br />

would often get together in the evenings to experiment with compositions.<br />

On other evenings, <strong>Mozart</strong> would go out to play billiards and bowl. Often he<br />

played concerts in the parks. All during this time he was busy composing<br />

and producing his greatest works.<br />

By 1787 however, his <strong>for</strong>tunes were turning. His behavior was becoming<br />

more erratic as his compositions were not being accepted by Viennese society,<br />

people who considered his music too difficult and unusual. The emperor<br />

told <strong>Mozart</strong> there were “too many notes” in his compositions. The stresses<br />

due to financial debt were weighing heavily on him. He had lost most of his<br />

students as a source of income. The important income <strong>for</strong> a composer then<br />

came from patrons or at least people to commission works <strong>for</strong> specific

per<strong>for</strong>mances. This was coming less and less <strong>for</strong> him. His financial situation<br />

was taking a serious turn <strong>for</strong> the worse. He had to move his family into<br />

a less spacious apartment. The irony is that the works he was composing<br />

at this time are now considered to be among his greatest. At the end of the<br />

year he had received 800 gulden as an imperial chamber composer’s salary<br />

<strong>for</strong> the dances he composed, but no longer was he receiving commissions.<br />

He wrote Don Giovanni and two String Quintets in C major and G minor<br />

(K.515 and K.516) in an ef<strong>for</strong>t to produce something <strong>for</strong> immediate sale. His<br />

father died in May of 1787 and <strong>Mozart</strong> received 1,000 gulden as his share of<br />

Leopold’s estate. In August, he completed Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, written<br />

in haste to make money.<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong>’s personal characteristics were described at the time as frivolous, eccentric,<br />

restless, mercurial, and expressing himself with grimaces and gesticulations.<br />

His close friend, Joseph Lange, the husband of Aloysia Weber,<br />

saw that the need <strong>for</strong> self-exposure and the radical letting-go as “a vent <strong>for</strong><br />

everything he denied himself in his music. For his music does not communicate<br />

his momentary state of mind but rather the creative process of his selfcontrol.”<br />

(Hildesheimer, p. 269)<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong>, 1789 painting by Christian Vögel

<strong>Mozart</strong>’s father told of a conversation with Franz Josef Haydn, one of the most<br />

respected composers on the continent: “Haydn said to me: ‘Be<strong>for</strong>e God and as<br />

an honest man I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me<br />

either in person or by name. He has taste and, what is more, the most profound<br />

knowledge of composition.”<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> fell ill on his trip to Prague in <strong>1791</strong> <strong>for</strong> the per<strong>for</strong>mance of his opera, La<br />

clemenza di Tito and his condition became worse when he returned to Vienna.<br />

In the last few days, his body was described as extremely swollen. He died on<br />

December 5. According to Viennese custom, he was buried in a common grave<br />

two days later.<br />

Over 200 years after his death, <strong>Mozart</strong> continues to be one of the most well<br />

known and beloved composers the world has known. He is famous throughout<br />

the world, with his compositions played wherever there are musicians or<br />

sung wherever there are singers. In his lifetime, <strong>Wolfgang</strong> <strong>Mozart</strong> composed<br />

19 masses along with numerous other sacred music pieces; 19 operas, musical<br />

plays and dramatic cantatas, three ballets; numerous vocal music pieces; 59<br />

symphonies, many concertos, serenades, divertimentos in addition to chamber<br />

music and other works. He composed masterpieces in all these <strong>for</strong>ms even <strong>for</strong><br />

instruments he was not fond of as well as <strong>for</strong> new instruments to the orchestra<br />

such as the clarinet. A good source <strong>for</strong> viewing the list of works is Sadie’s<br />

book. During his lifetime most of <strong>Mozart</strong>’s works were not published and at<br />

times not even kept track of. He himself did not start to keep track of his<br />

works until 1784. Most of the works prior to that are noted in the letters he or<br />

his father wrote. Immediately after his death, several European governments<br />

gave him their highest recognition and awards.<br />

So many interpretations have been written about <strong>Mozart</strong>’s life, his behavior,<br />

and his relationships as well as his prodigious works. Hildesheimer sums it up:<br />

“The evidence is massive, but we will find <strong>Mozart</strong> <strong>for</strong>ever puzzling and unapproachable.<br />

The almost continual creative activity of an intellect who towered<br />

so far above his society, and yet continually communicated with it and seemed<br />

to adapt to it, but who lived in it as a stranger, a condition neither he nor his<br />

circle could encompass; who grew ever more deeply estranged, never suspecting<br />

it himself until the end of his life, and making light of it until the very end—<br />

our imagination cannot accommodate such a phenomenon.” (p. 360)<br />

Following her husband’s death, Constanze took on the enormous task of organizing<br />

her husband’s works and getting them published under his name. In<br />

making certain her husband would receive the acknowledgement <strong>for</strong> the works<br />

he composed, she became a very astute businesswoman. She and her second<br />

husband, the Danish diplomat Georg Nikolaus Nissen undertook writing <strong>Mozart</strong>’s<br />

biography. They returned to live in Salzburg to be close to the sources<br />

of his work. It was through <strong>Mozart</strong>’s lifelong correspondence that his activities,<br />

views and works have been reconstructed as well as interpreted.

Illustration by Bonabel in Mörike, p. 55<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong>’s much commented on behavior is more clearly understood with the psychological<br />

tools of analysis available in today’s world. Drs. Edward M. Hallowell<br />

and John J. Ratey write in their book Driven to Distraction that “<strong>Mozart</strong> would be a<br />

good example of a person with ADD [Attention Deficit Disorder]: impatient, impulsive,<br />

distractible, energetic, emotionally needy, creative, innovative, irreverent,<br />

and a maverick. Structure is one of the hallmarks of the treatment of ADD, and<br />

the tight <strong>for</strong>ms within which <strong>Mozart</strong> worked show how beautifully structure can<br />

capture the dart-here, dart-there genius of the ADD mind.” (Hallowell and Ratey,<br />

p. 43) The discipline of the music <strong>for</strong>ced the structure on <strong>Mozart</strong>. Whatever<br />

drove <strong>Mozart</strong>, the world is a better place <strong>for</strong> the beautiful music he composed.

Contemporary productions of <strong>Mozart</strong>’s works take place all over the world.<br />

1998 production of Figaro at the Mariinsky<br />

Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia<br />

Productions of Don Giovanni at Indiana<br />

University and Opera Australia<br />

Production of Cosi fan tutte at the<br />

Theater an der Wien, 1994

Ideas to think about<br />

Can you think of any government today that employs its own<br />

musicians?<br />

What does it mean to say <strong>Mozart</strong> “appeared be<strong>for</strong>e the court”?<br />

Describe what you think it would be like to travel great distances<br />

by horse and coach in <strong>Mozart</strong>’s time.<br />

How many miles a day would be a reasonable distance to<br />

travel?<br />

What would you do if a wheel on your coach broke?<br />

Where would you stay overnight?<br />

Listen to some of <strong>Mozart</strong>’s music and describe how it makes you<br />

feel.<br />

How does one distinguish between an opera, a serenade, a<br />

sonata or a symphony? You will have to look up the<br />

definitions in order to do this.<br />

What would a salary of 150 gulden be worth today in dollars?<br />

Vocabulary words:<br />

clavier<br />

commissioned<br />

compose<br />

concertos<br />

gulden<br />

libbrettist<br />

operas (buffa and seria)<br />

patrons<br />

serenade<br />

sonatas<br />

symphonies

Selected Bibliography<br />

Anderson, Emily. The Letters of <strong>Mozart</strong> and his Family. W.W. Norton & Co., New<br />

York, 1985.<br />

Brion, Marcel. Daily Life in the Vienna of <strong>Mozart</strong> and Schubert. Translated from<br />

the French by Jean Stewart. New York, The Macmillan Company, 1962.<br />

Deutsch, Otto Erich. <strong>Mozart</strong>: A Documentary Biography. Stan<strong>for</strong>d University<br />

Press, Stan<strong>for</strong>d, 1965.<br />

Einstein, Alfred. <strong>Mozart</strong>, His Character, His Work. Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, New<br />

York, 1945 and 1962 (paperback)<br />

Hallowell, Edward M. and John J. Ratey. Driven to Distraction: Recognizing and<br />

Coping with Attention Deficit Disorder from Childhood through Adulthood. Simon &<br />

Schuster, New York 1994.<br />

Hildesheimer, <strong>Wolfgang</strong>. <strong>Mozart</strong>. Translated from the German by Marion Faber.<br />

New York, Farrar Straus Giroux, 1982.<br />

Mörike, Eduard F. <strong>Mozart</strong> on the way to Prague / ill. by Eliane Bonabel ; transl.<br />

and introd. by Walter and Catherine Alison Phillips. New York, Pantheon, 1947.<br />

<strong>Mozart</strong> : portrait of a genius / Norbert Elias ; edited by Michael Schröter ; translated<br />

by Edmund Jephcott. Berkeley, University of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia Press, 1993.<br />

Sadie, Stanley. <strong>Mozart</strong>: The Early Years, <strong>1756</strong>-1781. Norton, New York 2006.<br />

Schenk, Erich. <strong>Mozart</strong> and his times. New York, Knopf, 1959.<br />

Selby, Agnes. Constanze: <strong>Mozart</strong>’s Beloved. Turton & Armstrong, Sydney, 1999<br />

The Compleat <strong>Mozart</strong>. Editors: Zaslaw, Neal, with Cowdery, William. W.W. Norton<br />

& Co., New York, 1990.<br />

There are many websites devoted to <strong>Mozart</strong>, the following are very helpful:<br />

http://www.mozartproject.org/<br />

http://www.allabreve.org/storace.html<br />

http://arts.guardian.co.uk/fridayreview/story/0,,1560548,00.html