Of all the things, one of Robert and Clara Schumann’s grandchildren, Felix, ended up working as a door-to-door lingerie salesman in a New York suburb. On the morning of 25 October 1941, he was found slumped behind the wheel of his car, parked in a garage behind his house. Carbon monoxide poisoning. According to the New York Times, he had been “despondent because of poor health and financial reserves”. The death was recorded as a suicide.

In the Schumann family, suffering as a consequence of psychiatric illness stretched back generations. It is thought that Robert’s father had a nervous breakdown; his mother endured bouts of depression and would recover at what is now the Karlovy Vary spas in the Czech Republic; his sister Emilie took her own life. As for Schumann himself, he was troubled by severe psychotic episodes for his entire adult life, and attempted suicide in 1854, aged 44. At his own request he was admitted to the Endenich asylum near Bonn, where he died two years later. Furthermore, a son of Robert and Clara’s spent 31 years in an asylum.

To a psychiatrist, a history of mental health disorder in the Schumann family might point to a hereditary element to the illness. Yet in 1943, a physician called Heinrich Kleinebreil posthumously “diagnosed” Robert Schumann of dying of vascular dementia – a physiological, non-hereditary condition. The date of the diagnosis is significant. “The Nazis fashioned these great composers of the past in their own image,” says Erik Levi, author of Music in the Third Reich. “They were masters at rewriting history – musical history – and suppressing information if it suited their purposes.”

Schumann had been re-diagnosed at a time in Germany when people with psychiatric conditions were being murdered or forced to undergo sterilisation. It allowed the Nazis to promote Schumann as a hero of German Romantic music, but no serious psychiatrist before or after National Socialism believed Kleinebreil’s assessment was correct. Many other, more realistic diagnoses have been made, however, and continue to be made to this day. Trace these and you have a story bigger than Schumann – that of the naming of illnesses and the evolving stigmas surrounding mental health; a story of how we thought and think, and the values we held and hold now. It might also be the story of modern psychiatry itself.

In Song of Love, a wonderfully hammy 1947 biopic of Robert and Clara Schumann and their close friend Johannes Brahms, a doctor examines Robert, suggests to Clara that he might have “melancholia”, and then says: “I can’t say anything for certain truth. Melancholia, his mind … what does anyone know about the mind!? Hardly anything yet.” That soon changed. As David Healy, author of Mania: A Short History of Bipolar Disorder, says: “If you ask most people in the mental health field today who were the two big figures who shaped the way we view things, one would be Sigmund Freud, who would be thought of as shaping the mental approach we have towards things, and the other would be Emil Kraepelin, who shaped the physical approach – the idea that we’ve got diseases, illnesses.” Both were born in 1856, the year of Schumann’s death.

The most convincing diagnosis of Schumann’s illness and cause of death was first posited 50 years after his death. Hans Gruhle, a student of Kraepelin’s, suggested a double diagnosis: manic depression (now more commonly called bipolar disorder), followed by tertiary syphilis, for which there was no cure until the 1910s. His view was shared by two British psychiatrists, Eliot Slater and Alfred Meyer, who examined Schumann’s case in 1959, and also by Franz Hermann Franken, the first physician able to analyse the medical records from the Endenich asylum.

Schumann remains a source of intrigue to psychiatrists because of the wealth of material he left behind to study – extensive diaries, countless essays on music and letters, as well as his music. Carnaval (1835) has been the subject of the closest scrutiny. A suite of 21 short piano works, each representing different figures at a masquerade ball, it “stands as practically a catalogue of bipolar symptoms”, according to the American psychiatrist and pianist Dr Richard Kogan. In 2015, Kogan gave a talk at London’s Wellcome Collection about composers and mental illness in which he said: “You get the feeling sometimes in Carnaval that thoughts and ideas are racing quickly through his imagination, and even though he can’t get them all down, he is trying … I’m convinced that this piece could not have been written by somebody who did not have bipolar disorder.”

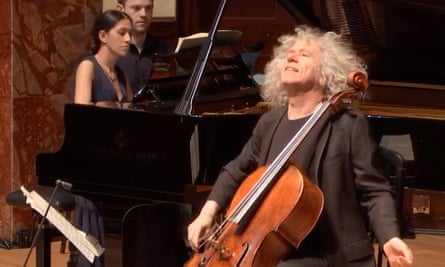

Bold statements like that have always cut another way. “While psychiatrists listened to Schumann’s music for evidence of illness, musicians began using psychiatric diagnoses to aid their assessments of musical quality,” wrote Yael Braunschweig in the New York Times in 2010. To this day, Schumann’s music sits awkwardly in the repertoire, with his late works often dismissed as symptomatic of a weakened mind. Not so, says cellist Steven Isserlis. An ardent defender of Schumann’s late music, he points to the Ghost Variations (1854) as an example of a misunderstood work. “I think they’re gorgeous – a farewell to life, really,” he says. “Between the penultimate and the final variation, he tried to commit suicide – he threw himself into the Rhine. So, you’d think that it would be disorganised, mad music. Not at all. It’s very contained and sublime.”

Without scans, X-rays, blood tests and the like we’ll never be able to establish a conclusive diagnosis of Schumann’s illness. “The music speaks for itself; there’s nothing that needs to be diagnosed in psychiatric terms about the music,” Schumann’s biographer Judith Chernaik argues. And yet, as Braunschweig says: “Schumann set this up for us by talking about relations between what was going on in his life and his creative process. People will continue to want to find these connections with mental health and that’s an important aspect of what keeps Schumann relevant for audiences. It keeps people listening to his music, because they keep on finding ways in which the music is relevant to their own lives.”

The Many Diagnoses of Robert Schumann is on BBC Radio 3 on 19 September at 6.45pm and on BBC Sounds for 30 days after broadcast.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion