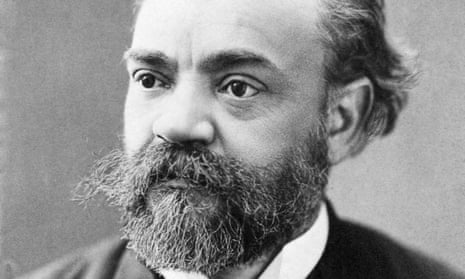

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) was a passionate Czech whose music transcended national boundaries and, indeed, crossed the world. A contemporary of Brahms and Tchaikovsky – his late symphonies standing with the finest of theirs – Dvořák is a wellspring of melody, with joy and anguish in equal measure. Yet, even if anguished, the music has a fundamental vitality.

The music you might recognise

Ridley Scott’s Hovis ad, voted the most iconic UK ad of all time, features the Largo from Dvořák’s Ninth Symphony, “From the New World”, arranged for brass band. In 1969, Neil Armstrong took a tape of this symphony on the Apollo 11 mission to the moon. Forty years earlier, Walt Disney’s 1929 animation Mickey’s Choo Choo had Mickey Mouse dancing on railway sleepers to Dvořák’s Humoresque. One of the world’s first trainspotters, the composer would have surely enjoyed that. Likewise, Jo and Laurie dancing (albeit anachronistically) to the scherzo of Dvořák’s “American” quartet in Greta Gerwig’s 2019 film Little Women. But would he have said Yes to Rick Wakeman basing his music for Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion around From the New World themes?

His life

Born in Nelahozeves on the Vltava River, just north of Prague, on 8 September 1841, Antonín was the first child of Anna and František Dvořák, a butcher. Their apartment was in a building where the ground floor was the local tavern, which his father also ran. There František played the zither for dances, so his son grew up hearing the rhythms that coloured his later compositions. Antonín learned the violin, then the organ, his obvious talent eventually lifting the abiding threat of life as a butcher. At 16, he left to study music in Prague. Subsequent years as a church organist, combined with teaching, spelled a frugal existence, but as a viola-player in Prague’s Provisional Theatre Orchestra Dvořák applied everything he learned there to his early symphonies, quartets and vocal works. At the theatre, he had fallen in love with an actress, Josefina Cermakova, but was rejected. In November 1873, he married her younger sister Anna. Their first three children died in infancy, but six healthy children followed.

Winning three Austrian state scholarships for composers in successive years helped his finances, but Dvořák’s most significant gain was the approval of juror Johannes Brahms, who introduced him to his own publisher, Simrock. Dvořák’s Moravian Duets were followed by the Slavonic Dances, an instant hit. While Dvořák and Brahms’s meeting in 1877 was the first of a lifelong friendship, in the short term, Brahms’s support – as Schumann’s had been for Brahms – was a boost to his confidence and his maturing style. In the G minor Piano Concerto of 1876, the Symphonic Variations and the 1879 violin concerto, Dvořák’s early devotion to Wagner and Liszt is tempered, refocusing on classical models yet faithful to his Czech heritage. That characteristic of a simple but haunting melody, often shifting between major and minor modes, perceived by Dvořák as a Slavic trait, was one he recognised in Schubert, to whom he acknowledged his debt.

At 42, Dvořák’s career stepped up another rung when he visited London in March 1884 to conduct his Stabat Mater. He was soon back for Worcester’s Three Choirs festival in September, where the 27-year-old Edward Elgar was proud to have played under Dvořák’s baton. The acclaim, plus the English appetite for choral works, saw him return often: he conducted his cantata The Spectre’s Bride in 1885 at the Birmingham festival; the 1886 premiere of his oratorio St Ludmila was in Leeds; his 1891 Requiem was another Birmingham premiere. One visit prompted a royal gift: two braces of English pouters and four braces of wig pigeons were dispatched to the Dvořáks’ Vysoká country home, the queen having ascertained from Anna Dvořákova that her husband was a pigeon-fancier.

Most important was the 1885 premiere of his Seventh Symphony in London with the composer conducting the Philharmonic Society, its commissioners. This darkly dramatic, lyrical work has come to be recognised as a masterpiece. Dvořák was indeed a master of orchestration and democratic too: all instruments – horns in particular – get wonderful lines. Yet, whatever the genre, his melodic invention threads through the texture, layering countermelodies: even the bass line of a harmonic progression can be a singing phrase. Tchaikovsky, hearing the Seventh in Prague, much admired it. At his recommendation, Dvořák visited Moscow and St Petersburg early in 1890 to conduct the Stabat Mater, by now a calling card. In 1891, he became professor of composition at the Prague Conservatoire. In Nature’s Realm, Carnival and Othello – overtures conceived as a trilogy – have a renewed authority, as does his Te Deum, a hymn of praise. Reaching 50, Dvořák might well have rested on his laurels.

…and times

Dvořák’s early life coincided with a massive expansion of the railway network across Europe. As a child in Nelahozeves, when Bohemia was part of the Austrian empire, he had watched the construction of the rail line linking Prague with Dresden and the train station built directly opposite the family home. The curious boy would become an intrepid traveller, eager to learn about rolling stock and to chat with train drivers. “I would give all my symphonies for inventing the locomotive,” he once said.

Dvořák seems to have kept in balance two apparently conflicting perspectives: the international one measured out in his frequent journeying, and a profound commitment to his Bohemian roots, in sympathy with the Czech National Revival movement seeking liberation from the Austro-Hungarian yoke. The first Czech-German dictionary, published from 1834-39, was key to the language and culture’s resurgence, as too was Karel Jaromír Erben’s Kytice, a telling of traditional folk-ballads rivalling the Brothers Grimm and felt to represent true Bohemia. The typical rhythms of dances like the dumka and furiant in Dvořák’s scores reveal his allegiance, but they also permitted him experiments with form. The Dumky Piano trio, with its six kinds of dumka, shows the variety of structure and tempo he sought.

Given his solidarity with the nationalist cause, Dvořák’s decision to accept the post of director of New York’s National Conservatory of Music is surprising. He had twice turned down the lucrative offer, but Anna felt $15,000 a year couldn’t be sniffed at, making the family vote on it. In September 1892, the Dvořáks sailed from Bremen on the transatlantic liner SS Saale. America was celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the New World, and there was a presidential election on (Democrat Grover Cleveland won). Jeannette Thurber, whose brainchild the new institute was, had studied at the Paris Conservatoire and with her millionaire husband’s money wanted an American equivalent, stipulating from the outset that women and African Americans could attend.

Hearing his composition pupil, Harry Burleigh, singing African American spirituals handed down from his grandfather, a slave who’d bought his freedom, Dvořák’s interest was piqued. Their intervals and inflections resonated with Bohemian melodies. He began to study them, discovering there “all that is needed for a great and noble school of music”, absorbing their characteristics when creating themes for his own compositions. This process of cross-fertilisation emerged in his Ninth Symphony, its subtitle “From the New World” a last-minute addition. At the Carnegie Hall premiere on 16 December 1893, there was thunderous applause.

But not everything was joy. The year had seen a serious economic depression: the Thurbers’ grocery fortune depleted and Dvořák’s salary was almost halved, and even then paid irregularly. Dvořák loved America, but was homesick. Consolation came in Spillville, Iowa, staying with the Czech community there, and at New York’s dockside spotting ocean-liners.

Longing for home found expression in his stirring Cello Concerto, which took on a greater poignancy on learning of the decline of his sister-in-law, Josefina. The new ending Dvořák gave his concerto reflected on her death but, at another level, it lamented a youth inextricably linked with hers. This work’s power to transcend boundaries was never more deeply felt than when Mstislav Rostropovich was soloist – tears streaming down his cheeks – with the State Orchestra of the USSR at the Proms in August 1968, the day that Russia had invaded Prague.

The family’s return to Europe in 1895 saw Dvořák exploring new musical ground. Five wonderfully atmospheric symphonic poems took inspiration again from Erben’s ballads; Gustav Mahler, conducting one in 1898, was “enchanted”. Some of the otherworldly character of these works anticipates the one opera of Dvořák’s to make a real mark, Rusalka, written in 1900, four years before his death. This water sprite’s “Song to the Moon” is a heart-wrenching affair. Perhaps Neil Armstrong should have taken that on the lunar mission too.

Why his music still matters

As well as raising American consciousness of its Native American and African American traditions – a stance seen by some as vindicated by the emergence of jazz – Dvořák influenced a new generation of Czech composers, whose work was even more implicitly nationalistic. He befriended the young Janáček, who would eventually develop his music differently, but his mentor’s example was crucial. Dvořák also influenced his violinist and composer son-in-law, Josef Suk, who in turn briefly taught Bohuslav Martinů. Martinů’s assessment of Dvořák said it best: “If anyone expressed a healthy and happy relationship with life, it was he.”

Great performers

Charles Mackerras on Supraphon was a brilliant interpreter of Dvořák, whom he regarded as the greatest composer next to Mozart. The London Symphony Orchestra’s recordings of the symphonies with both István Kertész and Pierre Monteux were revelatory. More recently, Mariss Jansons’ various discs are unfailingly insightful and expressive. The Pavel Haas Quartet bring great freshness to the quartets. Anna Netrebko’s affection for Songs My Mother Taught Me is obvious, while transcriptions of these songs by Dvořák’s violinist great-grandson, another Josef Suk, are an evocative link with the composer. Vladimir Ashkenazy accompanies Suk, who also plays his great-grandfather’s specially restored viola.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion