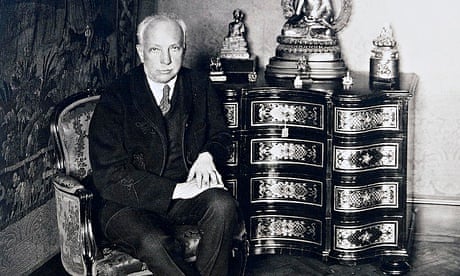

Richard Strauss. He's the firebrand composer who revolutionised the technical and expressive possibilities of the orchestra before the end of the 19th century in his tone-poems such as Also Sprach Zarathustra – 2001: A Space Odyssey's signature tune – or Ein Heldenleben. He shocked and awed early-20th-century audiences with his blood-drenched settings of Salome and Elektra. And at the end of his life, his beloved Germany in ruins after the second world war, he wrote some of the most devastatingly moving music ever composed: Metamorphosen, for strings, or the Four Last Songs. But in his 150th anniversary year, he's controversial: is he a fabulously gifted entertainer rather than a musical deep thinker? What was his real relationship with the Third Reich? Is his description of himself – "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer" – mere modesty or the simple truth? Tom Service

Mark Elder, conductor

It's difficult to be objective about Strauss. Like all good love affairs, my relationship with him started without any sense of proportion. I'd never heard any of his music before playing in a university production of Ariadne auf Naxos. I was flabbergasted. I had no idea music could do the things he was doing with harmony and melody. And the sounds of those female voices sent shivers down my spine. I set about playing and hearing and seeing anything of his I could, from orchestral music to the songs, and as many of his operas as I could find. As time has gone by, I'm a bit more selective, and today I'm fascinated by the fundamental question of how much profundity there really is in his music, as opposed to incredibly enjoyable and skilful entertainment. But I just love his musical imagination.

From a conductor's point of view, his scores are brilliantly conceived. The challenge is getting an orchestra to do exactly what he writes in them: but if they do, his music – no matter how dense or rich or complex – just works.

Susan Gritton, soprano

It is always a glorious treat to sing Strauss. He knew instinctively how to write for the soprano voice; you feel this particularly strongly in those songs he wrote for his wife, Pauline de Ahna. The richness of the orchestral texture is actually where the beauty lies for the voice because, with a sensitive conductor, it becomes a sumptuous wave for the voice to surf, with wonderful opportunities for timbre and line. The lieder written later for Elisabeth Schumann have a deeper, more thoughtful quality; you can feel they were composed for a different voice. My own favourite Strauss role is Capriccio's Countess Madeleine – it is rich with sparkle and lyrical elegance – and fits me like a glove.

Steven Isserlis, cellist

I can't say that I like Strauss, as a rule. I saw Salome once, and never need to see it again. His natural language is post-Wagnerian hothouse romanticism that I'm just not into – I long for a bath of Mozart after hearing it! But I do love Don Quixote, the piece based on Cervantes's novel, for solo cello and orchestra. The first time I heard it I couldn't make head nor tail of it, but the more you understand the story Strauss is telling, the more you get out of it. It's a brilliant piece of painting in music. It has such beauty and such colours – the section when Quixote explains his philosophy to Sancho Panza, or its ecstatic finish. There has never been another composer who had the skill and the genius of depiction that he did. He even said he wanted to be able to depict in music the difference between two kinds of beer. And I hope that this year, there will be some lesser-known works of his that will be played and will turn out to be masterpieces.

Roderick Williams, baritone

My favourite opera of his is Capriccio, in which he wrestles with the question of music and text – which comes first? It's an serious attempt to solve that riddle in operatic form while also being a witty and charming music drama. I always think it's like a Radio 4 Play for Today in its conversational texture, until the last 20 minutes, which is then sheer ravishing beauty. It's almost as if in this last scene Strauss finally relented, stopped thinking about music and text, and gave in to his melodic urge. There's this amazing horn solo, and Strauss just lets the Countess sing. I was in a production of it at Grange Park three years ago and every night I used to stand in the wings during this final scene and watch Susan Gritton sing. It was hairs on the back of the neck stuff.

Not only was Strauss married to a soprano but he was an opera conductor, so he understood orchestras and orchestration particularly well. Strauss's wife wasn't backwards in coming forwards and would have told him what worked. If he wasn't an intuitive writer before he married her, he certainly was after!

I was at a performance of the Alpine symphony in the US recently – and, hearing it live with 100-plus people on stage, Wagner tubas, quadruple winds, a kitchen sink, even a bass oboe – a heckelphone – for the duration of that piece I was right up there! Strauss took Programme Music about as far as it could go before cinema added visuals to it. After this is John Williams and Korngold.

Juanjo Mena, conductor

In 1896's Also Sprach Zarathustra, Strauss abandoned what he found to be the restrictive classical form, developing it to reveal a new structure that took the shape of a great symphonic work, but in one single movement. The process culminated in 1915's Alpine Symphony. In both works, Strauss was clearly conscious of presenting art as a form of expression, stressing that music should have poetic elements to it, as well as the most imaginative representations of living phenomena – those of man, life and nature. He channelled all this incredible optimistic energy into his scores in a masterly way, and his instrumentation, with its inexhaustible wealth of orchestral colour, is intoxicating.

Soile Isokoski, soprano

Every Strauss song and opera part I have sung feel as if they were written for my voice – they are like balsam in the throat. I really love his songs but my favourite of his works is Der Rosenkavalier, a dear challenge every time. It is such a perfect harmony between music and text, the terzet at the end being the crown. Just amazing.

William Dazeley, baritone

Strauss is a very personal thing. I know many people who either love or hate his music. I'm probably one of the rare breed who don't feel strongly either way – it depends what sort of a mood I'm in! Sometimes I find, particularly the late work, too much of an assault, emotionally and physically. The vocal lines of his pre-first-world-war songs have a beautiful romantic sweep but in later years he got more experimental and conversational. The song I'm performing on the 23 January's concert, Nächtlicher Gang, is a huge challenge. Written in 1899, there are hints of the kind of style he was to move on to in later years. It's wild and fiery – the marking at the beginning means literally "moving violently". It's got a crazy repeated refrain – "I must get to my beloved" – that comes seven times, each time a semitone higher, as if the singer is battling his way through the storm. You can imagine by the time you get to the end there's a high-pitched ecstasy of determination to beat the odds and make it through.

Anne Schwanewilms, soprano

Strauss's marriage of text and music demands the portrayal of genuine psychological and emotional depths. A perfect symbiosis developed over time between Strauss and his preferred librettist, Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Their correspondence reveals that they were often at odds regarding questions of interpretation, but this discord enriched their creative relationship, and allows the singer a variety of interpretative possibilities. Sometimes, a certain cynicism in the text may colour the phrase; other times, the instrumentation or use of a specific musical motif inspires the interpretation of a particular dramatic moment.

Inger Dam-Jensen, soprano

Strauss understood the female voice intuitively. His music has always suited my voice naturally, in every way. Technically it's demanding but it's also very natural to sing for a soprano - there's something about the melody but also about the vowels and where they are placed. But we should always reappraise people, and some do find Strauss difficult - my father, for example! It partly depends on which Strauss you're talking about. Salome is a very complex and quite modern work, and for some it still does feel "modern", but if you give it a chance you find melodies and great beauty in there even if the harmonies can be demanding.

Steve Davislim, tenor

I think Strauss's affinity for sopranos (and their voices) was so strong that it led him to try to actively kill his tenors – pick just about any of his operatic tenor roles! (Might this be the stuff of an upcoming mini-series?)

Strauss, as with all his contemporaries – Korngold, Schrecker, Zemlinsky – seems to have thought largely in terms of textures rather than volume. Who wouldn't want to include all those exquisite colours available within the late-romantic arsenal? He was pre-cinematic – look how his younger Nazi-deemed "degenerate" late-romantic colleagues were hounded to Hollywood sound stages in the late 30s.

But there is psychological and emotional depth crafted into his music albeit often well buried beneath a luxurious multi-overlay of lavishness sometimes verging on musical extravagance that apart from being his chosen individual musical style was also a reflection of the late 19th/early-20th-century decadence he saw around him. But who could hear the Four Last Songs and not feel eternity?

Hillevi Martinpelto, soprano

Both his music and his texts convey deeply human feelings, an awareness of the finiteness of life. Songs such as Im Abendtrot or Befreit feel almost too powerful. Much of it is technically very challenging to sing – you certainly have to be on your toes. My own favourite role is the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier. I love interpreting her thoughts and feelings on the passage of time and how nothing lasts for ever. I'm going to sing as much Strauss as I can this anniversary year. It's a fantastic opportunity!

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion