I first came across Jacques Offenbach's opera Fantasio on German radio about 20 years ago. The recording they were playing was much older still and wasn't authentic in any way. But it was enough to give an idea of the opera, and to ignite in me a passion to see justice done to a neglected but inspirational work of art. This weekend, when the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment perform Fantasio at the Royal Festival Hall, that dream will have finally become a reality: excepting a few cuts to the dialogue, Sunday's concert performance will represent the first full performance of the opera, as Offenbach originally intended it to be heard, since the work's premiere nearly a century and a half ago.

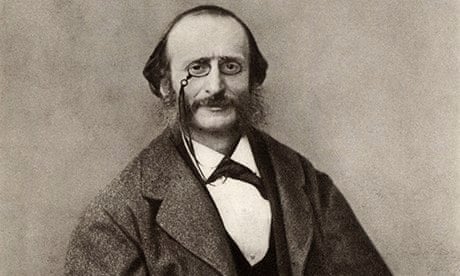

The name Offenbach is best known from the notorious nightclub routine that became the defining image of the belle époque, the Can-Can. Offenbach himself, who died in 1880, had no idea that a number from his opera Orpheus in the Underworld (the Infernal Galop) had developed a second life as the "can-can music", but the composer's reputation suffered immeasurably as a result. Even among the musically literate today, Offenbach is largely remembered for a couple of operas, the classic "opera bouffe" La Belle Helène, and his unfinished Tales of Hoffmann, a masterly piece of musical storytelling that nonetheless reveals only one side of the composer's musical personality.

Offenbach's reputation was no less problematic during his lifetime. As a German-born Frenchman living at a time of rising mutual mistrust between the two nations, his decision to compose an opera based on Alfred de Musset's 1833 play Fantasio couldn't have been worse timed. In 1872, De Musset was strongly out of fashion, far too "old-world" and literary for the tastes of a France looking for light relief after the depredations of the Franco-Prussian War. Offenbach himself was strongly associated with the Second Empire of Napoleon III. Worse still, his German origins meant he was now firmly detested by the musicians of the Opéra-Comique.

The first performances of Fantasio were a failure. Offenbach's friend Camille du Locle, the theatre's co-director, withdrew his support for the opera, leading to its withdrawal from the repertoire after only 10 performances. Offenbach shortly followed suit, near suicidal at the prospect of his great work's failure and withdrew from Paris to San Sebastian, where he had lived in self-imposed exile during the war.

Although the work fared a little better in theatres in Vienna and Berlin later that year, the original version of the score was lost when the Salle Favart – the home of the Opéra Comique – burned to the ground in 1887. In order to even begin compiling an authoritative performing edition of the music – part of the ongoing Offenbach Critical Edition launched in 2001 – I had to begin gathering together the various manuscript pages and autographs that had found themselves distributed themselves around the globe.

The original Paris version of the opera, which we were committed to restoring as being most consistent with Offenbach's vision, existed only in the poorly produced piano reduction published at the time. Two of the other major sources were in libraries – one in the British Library, another in New York – and so only proved a problem where it concerned the difficult task of reconciling the very different arrangements of the material prepared for the Vienna performances. The third set of manuscripts, incomplete but crucial, lay in the hands of Offenbach's descendants. Obtaining copies thus involved, first, a certain amount of detective work – tracking it down, page by page – and a considerable amount of persuasion. Still another important source was found in the archives of the French censor. The censorship of plays, libretti and books was still standard practice in those days, and the censor's office would naturally hold copies of the texts it handled – luckily because, without it, we would have lost all the spoken dialogue.

Offenbach took the failure of Fantasio especially hard because it was among his most ambitious operatic projects to date. He had invested a great deal of himself, as both artist and man, in its composition. The tragic-comic character of Fantasio himself – a lovelorn student forced to play the fool in order to pursue his passion for the Bavarian princess Elspeth – clearly appealed to the composer, partly because he felt it represented his own position as a serious artist increasingly typecast as a composer of light comic operas, or operettas, but also because he felt the pathos of the role would allow him to flex his musical and dramatic muscles.

And indeed, those who come on Sunday – or equally those who purchase the CD shortly to be released by Opera Rara – expecting a simple opera bouffe along the lines of La Belle Helène will be in for something of a surprise. The weighty qualities of the work are evident from the outset, and particularly from Fantasio's Act I ballad, which he addresses to the moon – an object of beauty no less beyond his grasp than the fair Elspeth, promised in marriage to Ismaël, Prince of Mantua – and which exceeds by some margin what is expected from a comic ballad. In the end, though, the "King of Fools", as Fantasio is crowned by his student friends, succeeds in winning his heart's desire. And with the prospect of the Sunday's performance, when my dream of seeing Offenbach's opera properly performed, I can only say I now know how he feels.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion