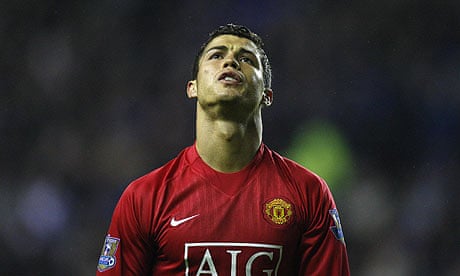

What we can now say with absolute certainty is that when he walked out on the pitch at the Stadio Olimpico on 27 May, he fully intended it to be the last time the world would see him as a Manchester United player. This might also explain why Cristiano Ronaldo then seemed so intent on creating more of his own history, shooting from all kinds of unlikely distances and angles. He, more than anyone, had helped his team reach the Champions League final but this was a night when his desire for personal glory blurred his mind. "He wanted to make it the 'Ronaldo final'," one United employee would later complain.

The allegation was obvious and in Rome that night it was tempting, as it has been so many times, to wonder what had become of the young man who arrived in England at the age of 18, with braces on his teeth and his forehead dotted with pimples, and quickly gave Manchester's paparazzi their shot – a photograph of the new boy holding hands with his mother, Dolores, as they crossed a busy shopping street.

Everything seemed so much more innocent back then. The teenage Ronaldo clearly had the talent to develop into one of the world's more penetrative footballers. And yet somehow it has become the story of a great football player, but not necessarily a great football man. There is a difference, one pronounced enough to mean that United's supporters might not be as devastated by the news of his impending departure as might once have been anticipated.

Ronaldo, you can imagine, would find that suggestion preposterous. He has, after all, been enthralling the Old Trafford crowd ever since he made his debut as a second-half substitute on the opening weekend of the 2003–04 season and immediately set about turning a 1–0 lead against Bolton Wanderers into a 4–0 thrashing.

The £12.2m signing from Sporting Lisbon was exciting, raw and talented and, while he may not have invented the art of dribbling, he seemed intent on taking it to its next level. Ferguson had paid him the ultimate compliment, assigning him the No7 shirt that is of such historic significance at Old Trafford, and everyone who was inside the stadium on that August afternoon must have been gripped by the sense that they were witnessing the start of something special. "It looks like the crowd has a new hero," Ferguson later volunteered.

That belief has been vindicated over most, though not all, of his time in Manchester, even if there have been periods, particularly in his first two seasons, when the obsession with stepovers and showy pyrotechnics would infuriate the United crowd – and, indeed, his own team-mates. Ruud van Nistelrooy grabbed him by the shirt during one training session. Others marked him down as a playground show-off who had stayed too young too long. But Ronaldo was willing to learn, to develop. He knew he had to listen to Ferguson if he wanted to achieve his ambition, to be recognised as the greatest player on the planet.

That thought quickly became an obsession, one that goes a long way to explaining the folly of his shoot-on-sight policy in last month's European Cup final against Barcelona. Ronaldo had scored a 40-yard goal in the quarter-final and another in the semi-final. The suspicion at Old Trafford is that he could not bear the thought of being upstaged by Lionel Messi in the final.

In mitigation, Ronaldo's performances in Europe over the last two seasons guarantee that he can leave Old Trafford having shaken off the allegation that his best work came exclusively against the smaller clubs. There was the time, for example, when he traumatised Bolton (again) so badly that his marker, Henrik Pedersen, was substituted after 28 minutes. Afterwards a reporter asked Sam Allardyce, the Bolton manager at the time, if such an experience could leave his defenders with psychological scars. "Scars?" he replied. "We're going to need a fucking plastic surgeon after that."

That destructive level of performance had become the norm, rather than the exception, once Ronaldo started playing with an adult intelligence about when to pass the ball, when to shoot and when to try his tricks. Yet it has been a strangely uneasy alliance at times. Ferguson has twice had to fly out to Lisbon to persuade him to banish thoughts of deserting the club – first in the aftermath of the 2006 World Cup, when Ronaldo was made a scapegoat for England's elimination, and second when he announced the "dream" of moving to Madrid last summer, claiming there was nothing more to achieve at United now he had won the Champions League.

Persuading him to return was a moment of man-management at its best, but for Ferguson it could also be described as a necessity. Ronaldo's physique had developed so that his torso now resembled that of an Olympic swimmer. He was the fastest player at the club, Ferguson reported. And one of the bravest, too. Ferguson would often talk about Ronaldo's courage in always wanting the ball when defenders were trying to point him in the direction of the nearest hospital. It resulted in him scoring 42 goals, wiping out all sorts of club records, in that European Cup-winning season of 2007–08.

A year on, Ronaldo again outscored Wayne Rooney, Carlos Tevez, Dimitar Berbatov and everybody else, this time with 26 goals. And yet the abiding memory of his final season may be of his body language – the strops, the apparent sense that the whole of English football was against him. It is difficult to pinpoint when this disillusionment began, but it did and it has seemed irreversible ever since Ronaldo started to dare take on Ferguson in view of the television cameras. In short, he has stopped looking comfortable in the red of Manchester United.

Ferguson, on the whole, was willing to indulge him because he understood Ronaldo's value to the side. Yet the Portuguese's behaviour has long been a concern to United's management, and not just on the pitch. In many ways he has been a consummate professional, rarely seen out late, always punctual, a devoted trainer. But there have also been reports of him being obnoxiously rude to various members of staff. The club's PR department were particularly embarrassed by his behaviour when he gate-crashed a press conference for the 50th anniversary of the Munich air disaster, angry and impatient because he wanted a lift from Rooney and was being kept waiting.

At the same time, supporters have begun to view him with as much unease as admiration, even suspicion. The flirting with Madrid and the transparent attempts to play the media have grated. One editorial in the Red News fanzine last season described him as "a 23-year-old prima donna". Red Issue went even further, branding him "a conniving little shit". There were times when the crowd stubbornly refused to sing his name and Ronaldo did not even bother to celebrate goals. The teenager had become a man and it felt like the innocence had gone.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion