Twenty-five years ago, Steven Spielberg brought out two of his best movies, in a matter of months. The films were poles apart in style and subject matter, and the process of completing one while shooting the other left the director exhausted and emotionally ragged. In spring 1993, Spielberg was in Poland, recreating the terror of the Kraków ghetto and the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp for Schindler’s List by day, and each night he was calling Industrial Light & Magic in California to oversee the special effects for the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park. Spielberg’s friend Robin Williams would call him up once a week to tell him jokes for 15 minutes at a time and release the tension.

Spielberg pulled off a similar double recently when he shot the political drama The Post in the midst of post-production for his blockbuster spectacle Ready Player One. With Schindler’s List in 1993, Spielberg couldn’t bear the thought of delaying the production of his Holocaust passion project for another year. With The Post, he felt that the story’s resonances with the current political climate were too urgent to wait. Likewise, the trailer for the 25th anniversary rerelease of Schindler’s List rings with the words “Now more than ever”.

By 1993, Schindler’s List had been on Spielberg’s desk for a decade. He was first given a copy of Thomas Keneally’s book after completing ET the Extra-Terrestrial in 1982. Keneally’s book is a novelized version of a true story: how a German industrialist and Nazi named Oskar Schindler managed to save 1,200 Jews from transportation to concentration camps. It’s a gruelling tale, and Schindler is not a conventional hero. He sets out as a profiteer, buying a former Jewish business in the Kraków ghetto, and exploiting Jewish labour to make enamelware to sell to the German army. As the war continues, Schindler can no longer stomach the regime and is moved to save a group of Polish Jews from the gas chambers. It’s a brave and righteous act, but one that pales in comparison to the scope of the Nazi atrocity. Nevertheless, a title card at the end of Spielberg’s adaptation informs that in 1993, as a result of the Shoah, there were only 4,000 Jews living in Poland, but around the world, there were more than 6,000 descendants of the Jews saved by Schindler. As is also shown in the film, the men and women that Schindler protected present him with a ring inscribed with words from the Talmud: “Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire.”

Spielberg shot his adaptation for a comparatively small budget of around $22m (about a third of the cost of Jurassic Park), in black-and-white, and in 72 days. Schindler was played by Liam Neeson, then a little-known actor, whom Spielberg had admired in Anna Christie on Broadway. Ben Kingsley played the crucial role of Itzhak Stern, Schindler’s Jewish accountant, who envisages the factory as a sanctuary from the camps long before his employer does. Ralph Fiennes, a relative newcomer at the time, played Amon Göth, the film’s snarling, sadistic villain – a grotesque SS officer who oversees the Płaszów camp, taking potshots at the workers from his balcony. The film’s story is as much about Schindler’s moral journey from complacent and mercenary womaniser to compassionate rescuer, from Göth to Stern, as wider Holocaust history. Cinematic flourishes such as picking out the coat of one little girl fleeing the SS in red become the dramatic signposts in this ethical transformation. She is both a lift from Keneally, who describes Schindler breaking down after seeing a girl in red, which gives him a clearer understanding of the scope of the Nazi scheme, and a nudge to the viewer, picking out one victim among thousands.

Schindler views the girl in red from a distance, when he surveys the liquidation of the ghetto from a hilltop. Along with the bleak dramatic irony common to many war films (the Jews frequently assert that things can’t get worse), one of the film’s dominant strategies is a conscious discretion over the amount of screen violence. First one or two are killed (symbolically, the first is a disabled man, as those with disabilities were first to be targeted by the Nazis) and then more and more, until we are faced with the terrible sight of ash falling like snow across Kraków, a sickening mass grave, and the ferocious Auschwitz chimney. In interviews, Spielberg has discussed certain incidents that were deemed too obscene to be filmed. One of the film’s most gruelling scenes remains the attempted murder of a rabbi, which is thwarted by a jammed mechanism in Göth’s pistol.

Schindler’s List is more than three hours long, and with such narrative care in Steve Zaillian’s screenplay, those accomplished lead performances, crisp and carefully lit cinematography by Janusz Kamiński and a sensitive John Williams score (featuring a violin theme by the Israeli American soloist Itzhak Perlman it is the definition of prestige cinema). Its sober tone seems to fold the unflinching testimony of Claude Lanzmann’s documentary Shoah into the hermetic narrative of a well-crafted novel, subjugating raw authenticity to emotional immediacy and the solace of a redemption story: a tactic that found a wide and generally appreciative audience. Schindler’s List was admiringly reviewed, recouped more than 10 times its budget at the box office and took home seven of the 12 Oscars it was nominated for, including best adapted screenplay, best picture and best director.

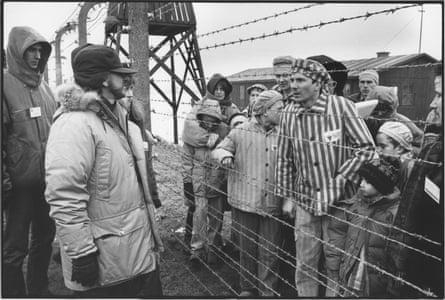

Before Schindler’s List, Holocaust cinema had been dominated by documentary, most notably Lanzmann’s Shoah and Alain Resnais’s Night and Fog, but after Schindler’s List, it seemed that a slew of narrative features were released, including Life is Beautiful, The Pianist and The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. But can a movie really begin to address enormity of the Holocaust? Especially a Hollywood film, and one such as this, which dwells on the heroism of a gentile capitalist, arguably above the suffering of the Jews? Stanley Kubrick, who had his own never-realised Holocaust project in the works, is said to have been doubtful. “Think that was about the Holocaust?” he reportedly said. “That was about success, wasn’t it? The Holocaust is about 6 million people who get killed. Schindler’s List was about 600 people who don’t.” Still, historian Peter Novick has identified Schindler’s List, together with Shoah and the 1993 opening of the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, as key events in the creation of what he calls “Holocaust consciousness”. Not only does the movie bear witness to the events such as the vicious liquidation of the ghetto, but also becomes a memorial of its own via the controversial coda, in which survivors from Schindler’s factory lay stones on his grave arm-in-arm with the actors who played them.

Surveys this year in the US and Europe suggest that our collective memory is failing us, with nearly a third of Americans polled vastly underestimating the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust and 34% of Europeans claiming to know little or nothing about the atrocity. Harrowingly, these polls accompany a resurgence in antisemitism and even Holocaust denial. Spielberg was born in Cincinnati just after the war and has described incidents of casual antisemitism from his childhood, as well as the time a Holocaust survivor taught him how to count using the numbers on his forearm tattoo. “This is something that I think, in a way, somehow led me to want to tell a story of the Shoah,” he has said. “Not the story of the Shoah, because there are millions of stories of the Shoah. Six million of them we’ll never hear.”

For Spielberg, telling Schindler’s story was a tool to combat ignorance, but it is work that continues. After making the film, he recorded the testimony of many thousands more Holocaust survivors in a video project called Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation. Keneally himself had first heard about Schindler from one of the men saved, Leopold Page, who would tell his tale to the customers in his Beverly Hills luggage shop, hoping that the word would get out. Via Keneally, and then Spielberg, it reached the widest possible audience – and now the film returns to our screens just when we need to hear this story the most.

Schindler’s List will be rereleased in the US on 7 December and in the UK and Australia on 27 January