Back in 1965, the art writer Grace Glueck described Ray Johnson as 'New York's most famous unknown artist'. It seems Johnson never quite shook off the tag – nor lived up to it, even, despite a prolific, sustained and fascinating career. While his friends and contemporaries – Cy Twombly, James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol – are among the most celebrated names of the 20th century, Johnson is, at best, a cult figure; at worst he is forgotten. The first major UK exhibition of the overlooked American pop art and mail art pioneer, at one of east London's newest spaces, is an exhaustive, museum-style survey of a life's work.

Like Warhol, Johnson was obsessed with popular culture. In the early 1950s, though, when he started making collages using newspaper images of pin-up boys such as Elvis, he was going it alone. The pin-ups were anathema to the presiding New York art establishment, which was dominated by the abstract expressionists with all their highbrow spiritualism. And unlike Warhol, Johnson's approach to stardom was personal and peculiar. He embellished mass-produced images with abstract patterns, hand-painted annotations and doodles – which, notably, included phalluses, among other references to gay subculture.

Johnson would doubtless be surprised to see his output – comprising hundreds of these drawings and collages – accumulated and lavishly installed across eight galleries and three floors . When he (apparently) committed suicide in 1995 by swimming out to sea – an act considered by some to be a final artistic gesture – it was a sad end to a career spanning almost five decades. An irresistibly romantic and contradictory figure, Johnson seemed to be buddies with everyone, yet he was no mere scenester.

From his earliest days as an artist Johnson seemed to hover between centre stage and the margins, though perhaps as much through circumstance as by choice. Even when Robert Rauschenberg included a Johnson collage in his seminal assemblage work Short Circuit in 1955 (which also featured Jasper Johns's first Flag painting), Rauschenberg thought that his friend had been overlooked. But Johnson was already cultivating an outsider position. He had been drawing on letters and sending his work to a few curators since high school, and in the 1950s began systematically mailing small collages to a cherry-picked audience. A series of Lucky Strike collages sent to his friend Bill Wilson seems full of opaque private jokes, though one memorable image, of a cat's yawning, glistening maw overlain with the black hole of a Lucky Strike logo, is instantly comprehensible.

While occasionally exhibiting in galleries until the 1980s, most of Johnson's work was tirelessly distributed by post to other artists, with whom he would ping-pong ideas back and forth. He christened his initiative the New York Correspondence School. Its members might be friends or artists who interested him, and work often arrived with the imperative 'Please add to and return' – the title of the new exhibition. If you responded, you were in. While Johnson is considered the founding father of mail art, an anti-commerce art movement begun in the 1960s, his notion of art as network clearly has far-reaching repercussions for our own age.

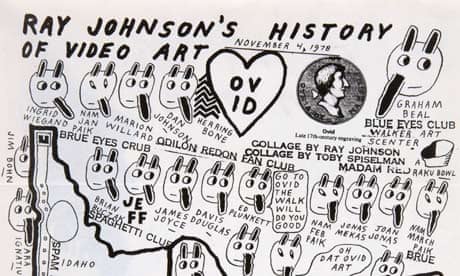

Look closely at his drawings, though, and this resistance to officialdom seems conflicted. They are filled with the names of successful artists as often as those of movie stars, all laid out in neat rows like a hand-drawn phone directory – or, in one fabulously funny piece, employed as labels for spots on a Shirley Temple-headed centaur. Johnson had a wry take on the art world's particular brand of celebrity, but these works are also animated by the ardour and manic compulsion of the true fan.

Indeed, while Johnson's work is pioneering, it is also very much informed by prevailing artistic ideas. His immaculately laid-out rhythmic collages show the influence of Bauhaus emigre Josef Albers, who tutored him at the legendary Black Mountain College, passing on modernism's preoccupation with geometry and form. You can sense John Cage's Zen Buddhist-style love of free association in Johnson's edgy conjunctions of pop imagery. And another collage – comprised of a photo of James Dean flanked by a horse's rear-end , set within a sea of scatological pictograms and a delicate spattering of pink paint – has all the energy of an experimental jazz freak-out. Conflating Fluxus and pop art, while playing perhaps on his own lack of fame, Johnson once described his work as "flop art".

Visually seductive and engrossing, the show marks an auspicious beginning for Raven Row, the latest privately funded, not-for-profit exhibition centre to appear in London. Its founder, Alex Sainsbury, comes from a family who, in addition to being a household name , have an impressive history of art patronage, including funding the Sainsbury wing of the National Gallery. But in a city chock-full of culture, and with the reopening of the Whitechapel Gallery providing a fresh focus point for art in the area, Raven Row also claims to being one of a kind. Private foundations have a tendency to exhibit a collector's taste and wealth as much as their art, but Sainsbury has said that he's primarily concerned with exposing little-known work. On the basis of this exhibition, it seems there is still plenty of room for the space.