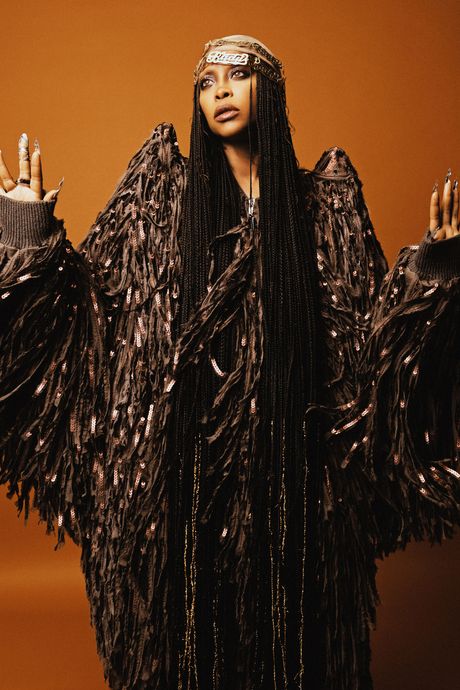

She stood alone atop a black staircase before a megascreen that had all night projected many curious symbols — digital mitochondria, ancestral totems, a beetle — but would soon show a giant moon. Till then, it was just her. Just her and me, just thousands of Mes watching their own private Her. It was late July in Dallas, in the blunt-filled dark of the American Airlines Center, during one of the hottest summers we’ll ever experience until next summer. Time had come for Erykah Badu to sing “Orange Moon.”

From the keyboard trickled pools of ascending notes, and under those keys crickets chirped softly. Everything was very still, everything was the memory of your first great summer lover — then she nosedived into the first lines:

I’m an orange moon

I’m an orange moon

Reflecting the light of the sun

The drums locked in. Three background singers oohed on cue. Then Badu’s voice — which some compare to Billie Holiday’s, though she compares it to a clarinet — pulled us through the song, from her album Mama’s Gun. It’s a tale of a man who’d spent so many, many, many nights all alone because his light was too bright. Until, one day, he turned to her. He saw his reflection in her. He smiled at her. He said to her: “How good it is.”

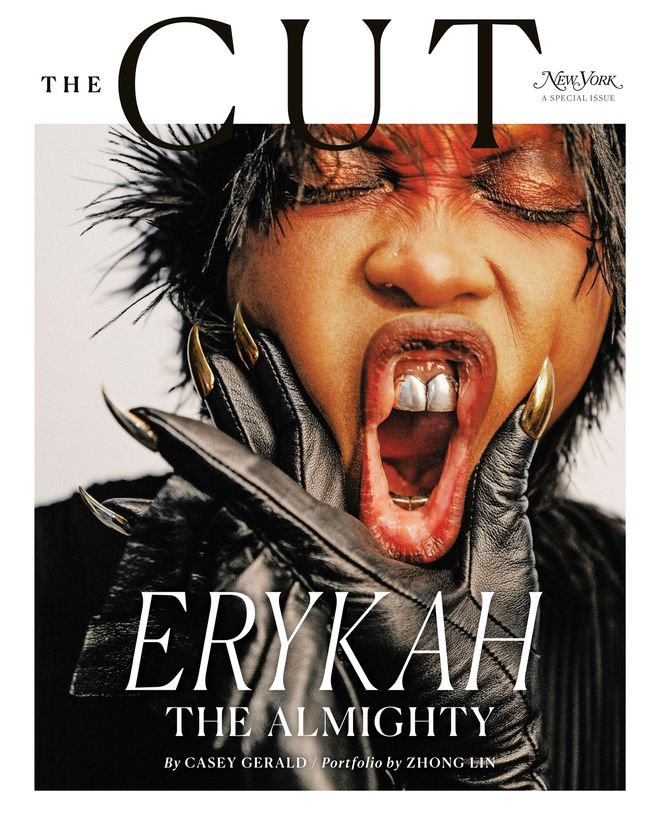

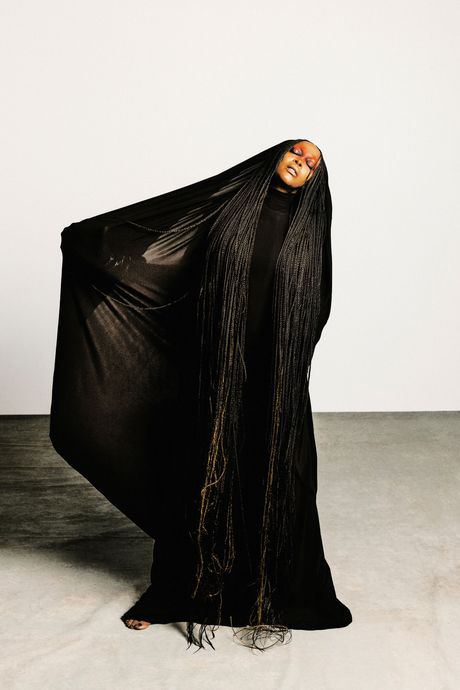

Cover Story

Their tale went on, and soon it was Badu realizing “how good it is,” sweetly singing “how good he is,” wailing “how God is.” Nearby, a few entranced listeners were on their feet, just some of the thousands she played to during her 25-city Unfollow Me tour this summer. One sister held her hand high in praise, in “yes,” as she swayed, and soon Badu’s eyes were back up on the megascreen in double. The moon returned, bigger and oranger, and the crickets and keys brushed up against each other in pace with Badu’s aching voice, musing howgoooditisss, so many different ways and wonderings, until she landed, softly, finally, on a solitary syllable, ooooooooo.

“And when she finished that last note,” Curtis King told me of Badu’s performance of the song in D.C. this summer, “the place just e-rupted. It was one of the most incredible things that I have witnessed or experienced in American theater — in entertainment, period.”

King would know. He is the founder and president of the Black Academy of Arts and Letters in Dallas. In 1975, he spotted a 4-year-old girl from South Dallas at the local rec center. She was funny. She seemed always “above the fray.” Most of all, she had talent. King told the little girl’s godmother, Gwen, and mother, Kolleen, “This young girl is going to be a great artist, and she’s gonna do re-mark-able things around the world.”

King was there when that girl, Erica Wright, starred as Dorothy in a local production of The Wiz. He was there when Erica Wright became Erykah Badu by her own will and invention. When Badu was in her early 20s, a manager named Kedar Massenburg booked her as the opening act for a young artist he represented — a largely unknown singer from Richmond named D’Angelo. That performance led Massenburg to sign Badu to her first record deal, and that record deal led to her 1997 debut album, Baduizm, which earned three platinum plaques, four Soul Train Music Awards, and two Grammys, including Best Female R&B Vocal Performance for her enduring hit “On & On.”

“Erykah cut through like a knife in one of the darkest times,” Terrace Martin, who helped produce Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, told me. Martin met Badu in 1998 at jam sessions around Dallas. He calls her “the Queen”: “Erykah has been like our Betty Carter, our Ella Fitzgerald, our Sarah Vaughan, all in one. And she’s been our MC Lyte, our Queen Latifah — I mean, she has all these powerful women in her left arm!”

If you’re thinking that’s a wide, wild variety of women, then you’ve already grasped perhaps the most important fact about Erykah Badu. A fact embodied in one of her most memorable sonic creations, 2015’s “Cel U Lar Device.” She produced this song, a reimagining of Drake’s hit “Hotline Bling,” in the childhood bedroom of Zach Witness, then a 21-year-old artist who’d idolized Badu since seeing her on Nickelodeon when he was 5. “This woman came on with incense, a headwrap, and tea,” he said of his late-’90s conversion. Nearly two decades later, now in her headwrap-free, grill-wearing era, Badu knocked on Witness’s mother’s front door. She spent 11 days working with him, once bringing along her friend and ex-lover André 3000, and left with an 11-song project, But You Caint Use My Phone. She also left Witness with numerous versions of “Cel U Lar Device,” versions he kept begging his idol to choose between. She suggested, casually, “We should just put ’em all out.” Eventually, Witness arrived at a quite Badulian solution: “I took all the best parts from all these different versions and weaved it into this megaremix.” It could be said this is what Badu has done her whole career and life — and pushed others to do as well. “So much of who I know myself to be,” Witness says, “she helped me discover.”

Alongside the powerful women Badu carried in her left arm were the many powerful women, men, and cosmic energies behind and inside her. It is assumed, of course, that any extraordinary Black American is magical in the literal sense. That they poofed from nothing and nobody against such nasty odds that we should never say a word about how those odds became so nasty. But you must know Badu comes from somebody, who came from somebody, who came from somebody, and on and on. There are the women who raised her — not just her mother and godmother but her maternal grandmother, Thelma, and paternal grandmother, Viola. There are the masters she studied as a young artist. Stevie and Marvin and Chaka Khan; Monk and Bird and Miles, whose presence can be felt not in Badu’s sound but in her silence, her “ability to manipulate space within a song,” as Martin puts it. While we’re on the subject of hearing silence, I should add that Badu believes she has long been clairaudient and clairsentient. That she once came to believe, during a past-life regression years ago, that she had lived as Jesus Christ.

This might explain why we must look beyond the music to grasp why she meant and means so much to so many. While the hip-hop heads saw the Queen as a possible heir and consolation to their fallen kings, many spiritual wanderers and cultural rebels saw Badu’s rise as a symbol of their own rise and revolution. Tina Farris, longtime tour manager for the Roots, first met Badu on a tour bus in 1999 and “thought I was gonna lose my mind.” But the allure was personal. “I’m 20-something. She’s 20-something. I want to be in love. She in love. I wanna be fly. She fly. I’m gonna wear a headwrap because that’s what she wear. I’m a kid, you know what I mean? Having an experience.”

Saul Williams gives a broader view. He met Badu in the ’90s, not long after she arrived in Fort Greene from Dallas, and performed with her at a Brooklyn Moon open mic before Baduizm dropped. Williams later wrote the liner notes for D’Angelo’s Voodoo, from 2000, an album recorded in the same studio that Badu used for Mama’s Gun. In those Voodoo notes, Williams wrote, “As traditional churches have grown empty many of us have been left to wander these haunted castles like that displaced Prince of Denmark, contemplating the paths of our mothers.” When I speak to him 23 years later, he stresses that this generational wandering was one current of the wave that lifted Erykah to the top — a wave of young Black people waking up. “Many of us were already vegan, many of us had stopped going to church and were wearing African pendants and burning incense, dah dah dah.” Finally, with Badu, “one of us was standing in the spotlight.” Along with Lauryn Hill and D’Angelo, Badu formed a troika of fiercely independent, gorgeous artists whose R&B records were “mixed with a hip-hop mentality,” in Williams’s words, who showed up exactly when their people needed them. Showed up like Black Messiahs.

I was 10, 11 when all these first things happened, living right in Dallas, and it never occurred to me that Badu’s headwraps and ankhs and lyrics meant any enormous thing. I picked up my kente stole at Black Images Book Bazaar just like all my classmates; I too shouted “Kujichagulia! Self-determination!” at the Black History Month assembly. I was not, in any way that I knew of, part of a revolution — perhaps because I was so suffocated in Baptist respectability that revolution seemed just another word for sin. But I remember my auntie turning up “Tyrone,” from Badu’s live album, when it played on K104, and I remember sneaking off to sing the “shit” out loud, when I usually stopped, was forced to stop, after “I’m gettin tieeeed of yo’ — .” I remember driving from my hood, Oak Cliff, to Badu’s hood, South Dallas, to see my granny’s brother and feel rich and clean and superior for an afternoon if only because other people’s dilapidation always looks dilapidateder than yours. I remember, most of all, as Badu shared at her Dallas show, “walkin’ up and down the streets” of the city, “starin’ at the puddles on the ground, tryna figga outta way up out dis town.”

So when Badu and I wind up speaking for three hours and 54 minutes and 22 seconds on a recent Sunday — a conversation so long and so Black she joked, “I feel like I been arguing with a nigga all day,” once we finally escaped each other after our 100th “Imma let you go” — I am not surprised to hear that Erica Wright, at 15 years old, wrote a letter to the Universe. The letter read, simply, “I’m gonna make it with the help of God. Nothing can stop me but me.”

In the beginning,” she starts her story, around A.D. 2000, her then-boyfriend, the rapper Common, arranged a trip to Cuba. This was just after Mama’s Gun came out. Badu wanted to receive a Santería reading, so she and Common traveled to Havana to the house of a well-known priest. They waited with many others out on the curb. “I had on my best whites,” she remembers. “Long white dress. I didn’t have any shoes on. But I had on a verrry tall white headwrap. I was clean.” She means this in the literal sense. “So I’m sitting on the curb and I’m waiting. I’m meditating. I’m breathing. But I’m annoyed.”

A man who was unknown to her, who apparently had no clue that next to him stood the Queen, casually passed a burning cigarette to another man, who stood on Badu’s left. She could see his dirty fingernails as he reached across her. “I look down at the guy who passed the cigarette, and he had on,” she takes a quick deep breath, “some Pumas that was tied so tight that you couldn’t see the tongue of ’em.” The Pumas were once blue suede, she says, but they had turned a kind of grayish color: “I just remember these details and being annoyed by them passing a cigarette over my good. White. Muslin. Dress.” The precision in her voice seems meant to suppress (or match?) her two-decade-old disgust.

“So it was finally my turn,” she says, “and the priestess comes out. She’s a short lady with white-gray curly hair, about my complexion. I’m kinda an orange complexion,” she adds, as if I’d never seen her before. “She had on a long yellow dress. And in the culture of Santería, just like Yoruba, Ochún represents yellow. So I was sure that Ochún was my head mother.”

The priestess walked Badu into the house. They sat on the floor. The priestess began to prepare Badu’s body, taking some cotton and making rubbing motions around her head. “That means clearing your head so that you can receive — or give, if necessary.” Then, somebody else came in. The worst possible somebody. “It was the dude with the dirty fingernails and them suede Pumas tied tight. Tight.” To add insult to his Pumas and still-burning cigarette, he was now drinking a beer. “I looked at Pablo, who was the interpreter —Common’s friend, who brought us down to Cuba, which was illegal at the time — I looked at Pablo and I said, ‘Eyyyy, c’mon man. This, you know, this ain’t it.’”

Badu pauses, and when she speaks again, her voice is so serious it sounds as if she hasn’t laughed a single time over the past seven minutes, or ever. She tells me Pablo looked at her and said, “He’s the priest.”

“I think I exploded into glitter,” she says in fresh disbelief. The Puma Priest, she later learned, had come from a long line of healers. “And there was nothing that he could wear — or not wear — that would erase that history.”

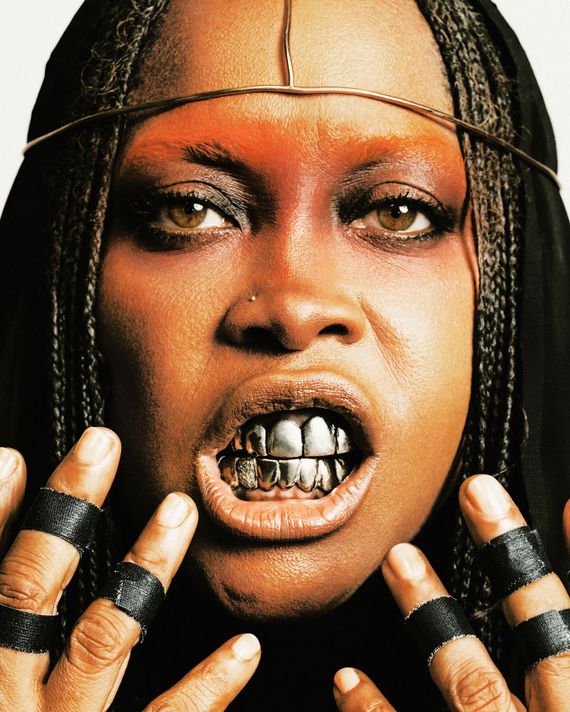

Up till then, Badu’s headwrap — and the incense, the ankh, etc. — was Erykah Badu to many followers and even to her, to some extent. “I got special treatment on the airplane when I had that big dignitary headwrap on. I got special treatment in the hood. I got special treatment everywhere because doesn’t that look like a swami? I think so. No matter what I really knew, they just respected me because of that and the way it looked.” She sounds almost angry at her younger self. “I didn’t wear the headwrap anymore after that day — not in that way.”

She knew losing the headwrap was a risk since “many people are not looking for a leader. They’re looking for someone who looks like one.” And now that look was gone. “I was evolving and growing, still, and dedicated to the work, you know? But people saw it as me changing. That I was different, changing, different,” she circles around this in a loop of painful memories, “and I couldn’t explain because it wasn’t important to me anymore to explain.” She trails off, then whispers again, “To explain …”

Curtis King helps explain: “People don’t understand things about Erykah because she’s constantly unraveling things about herself. And that’s a positive thing as an artist, because the world is constantly changing, and because the world is bending and shifting, she bends and shifts with the wind of the world. Then she gets in the ocean and she goes with the current and — because you don’t know where the wave’s gonna take you — she trusts enough that it’s going to be okay, that she’ll land on another shore.”

I heard that trust and searching in Badu’s voice when she told me why she pushed through all her fears, and some fans’ harsh reactions, to let her headwrap go. “I wanted to see what I was made of.” She fell silent, perhaps reviewing what she saw. “And that’s the path I’ve been on since then.”

She lost the headwrap but regained her freedom, which showed up in the music and beyond. “For the first time in her career,” Mark Anthony Neal, now a professor of African and African American studies at Duke, wrote of Badu’s third studio project, 2003’s Worldwide Underground, “Badu is wearing her own voice.” She had left, he noted, “the road to deification,” choosing instead a musical playground where she could, in her words, “groove for a long time” on Badu-canon songs like “Danger,” whose lyrics — The trunk stay locked / Glock on cock / The block stay hot / Block on lock — probably seemed worlds apart from the invocation of “peace and blessings manifest” from “On & On.” Turns out she’d just remixed herself; “Danger” sampled headwrap Badu’s 1997 single “Otherside of the Game.”

Her two most recent studio albums, New Amerykah Part One and Two, dropped in 2008 and 2010, that interregnum between the new Black Messiah’s arrival (Obama) and the revelation that no one, not even He, would save us from this mess called America — a lesson Badu taught us on “Master Teacher,” from New Amerykah Part One, when she said to “stay woke.” Badu was so in tune during these New Amerykah years that the writer Sasha Frere-Jones, after witnessing a summer performance at Radio City Music Hall, declared online, “If you want to know who is at her peak, who is both of her moment and channeling so many forces that her work spills out over the edges of history and stops time, that’s Erykah Badu in 2008.”

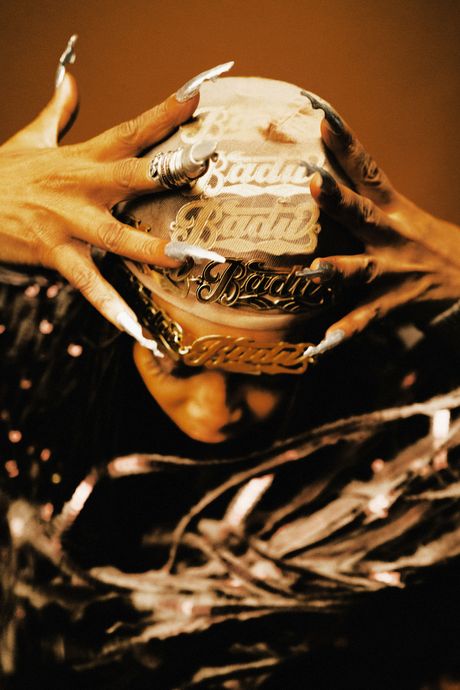

In the years that followed, Badu’s live shows only grew more ecstatic, culminating in this summer’s tour-cum-ritual. She’s also been busy in other realms: an online store, Badu World Market, where you can buy Badu Pussy Premium Incense; film roles; Fashion Week appearances (“I’m gonna go to Fashion Week, but I’m gonna go to every motherfucking show and I’m gonna turn that motherfucker out”); three beautiful kids and a robot named P-Funk. When she tells me, “If the car movin’, I’m drivin’,” she clearly means much more than her dove-gray Porsche, whose license reads SHE ILL.

It seems to me this was not a new path but the same path that led Erica Wright to write her letter to the Universe at 15. When I ask if she saw that letter as a bargain, the kind of crossroads deal Robert Johnson made in return for his blues genius, she clarifies: “There is no bargain unless you make a deal with the Devil. The deal with the Devil they be talkin’ about works like this: You make a deal to be famous by any means necessary. You say, ‘I will give up my integrity, and I don’t care about anybody else’s art.’ That’s another kind of declaration.”

The Cuban headwrap crisis was a reminder that Badu had not set out to become a leader or even a star. She’d set out to be an artist. She texts one day after we speak: “Artists should hold on to our originality fiercely, be flattered by imitation but never silenced, always ensuring our voices are heard, our ideas acknowledged, and our integrity respected. The path isn’t easy, but the love for creation, that irresistible pull towards self-expression, makes it all worth it.”

The Path, that old black magic, comes at a cost. “My biggest fear is the same as my biggest hope,” she confides. “That I am seen.” When I wonder what she fears might happen if she’s seen, she answers quickly, honestly: “I don’t know. I haven’t even thought that far. It’s just some kind of barrier, you know, some kind of thing that makes me afraid.” Thinking it over, she alternates between defiance and anxiousness: “You can’t shame me. You can’t creative shame me. You can’t What-nigga-I’m-with shame me.” She pauses. “You can hurt me, though. You wanna do that? You wanna hurt me?”

I really don’t, but I do ask about some of her controversies. Many couldn’t understand, for example, why she said she was “putting up a prayer” for R. Kelly. She admits to me, “I’m scared to express things that are not the most popular opinion,” but holds firm: “I’m confident that my truth is relevant, so I go ahead and say it.” This seems to be what happened in 2018, when Badu told this magazine, “Hitler was a wonderful painter.” The exchange began, in fact, not with Hitler but with a discussion of Louis Farrakhan and antisemitism. Badu refused to denounce Farrakhan, clarifying that she is not an antisemite but asserting: “I don’t choose sides. I see all sides simultaneously.” She sees good in everybody, she told the interviewer. She even “saw something good in Hitler.” She later admits that maybe he wasn’t such a good painter, but doubles down on her broader point — not least, I bet, because the fundamental energy had turned into the interviewer, a white man, trying to lecture or rebuke a Black woman about her moral compass.

The real thing you should know is that her broader point was the Point of the past-life regression I told you about, when she discovered she’d been Jesus many lives ago. Badu had been ashamed, not proud, of this discovery. “We’ve all been Jesus,” the healer told her, meaning that we’ve all been the Holy One and also all been the Monster, perhaps many times. “My question is,” the healer continued, “Did you get the lesson?”

If you don’t believe this past-life stuff, it’s hard, if not impossible, to see a sane lesson in Badu’s statement, which she explains in part by saying, “It’s the Pisces in me.” Pisceans, I’ve heard, sometimes see lots of good in folks they really should see Real Bad in. I sense this, for example, in her later comment from that same interview: “I would never even want a group of white men who believe that the Confederate flag is worth saving to feel bad. That’s not how I operate.” With an operating system like Badu’s — the operating system of someone determined to be free at all costs — it’s no surprise she catches so much hell, sometimes from folks who once adored her and may adore her yet again. After the latest online conflict, one sister tweeted that Badu “is like that favorite aunt of your childhood who grossly disappoints you when you get grown and see them for who they are.”

Let me be as clear as I possibly can: Erykah Badu is not like your aunt, not even your favorite one. I’ve met presidents, mayors, billionaires, Dallas Cowboy Hall of Famers, Holy Land juice healers, TED Talkers — a lot of people, all over the world, and Badu is one of the few who holds up after close inspection. I don’t mean she is perfect. I don’t mean she is better than you or anyone else. I mean she is who she says she is; she is trying to be better than she’s been. Most of all, she seems to truly like, or at least accept, herself. When I learned and saw that she walks barefoot nearly everywhere, and wondered how in the world she keeps her feet clean, she answers, “I don’t. They be black as hell!”

Hours after her Dallas show, a few dozen fans lingered in the basement of the American Airlines Center waiting for Badu. Her imminent arrival was announced, and a loose receiving line formed, then lost all structure when she entered, barefoot. As she walked toward the small crowd — most seemed under 25 — some hooted wildly and gratefully. A young girl rushed and hugged Badu like a child whose mother finally comes back home from war. All gathered around in a circle, close.

Amid the crowd, Badu tried to speak but started coughing. She’d been coming down with a cold, I learned days later. She’d been grieving her dear friend and former musical director, Daniel Jones, whose sudden death had been announced just days before. “That smoke tore my ass up,” she said, laughing between some coughs, referring to the stage smoke that she sang and danced in for two hours. “Well, you sang yo ass off,” somebody hollered. “You know what?” she said, leaning back on her heels, lifting her eyebrows. “That’s all I had.”