Should Paramilitary Murals in Belfast Be Repainted?

Neighborhood walls have become the latest battleground in the city's struggle over how to commemorate its violent past.

BELFAST, Northern Ireland-- "For the longest time, my granddaughter believed my scar was from an alligator bite," Danny Devenny says with a smile.

But the true origin of the long, linear scar on his forearm is darker, a symbol of a country in which such wounds -- physical, emotional, historical -- are an undeniable part of life.

On an especially chilly afternoon, the renowned muralist is sitting in front of a small space heater in his studio when he recalls the day he was wounded. His fingers, cracked from the cold, deftly roll a cigarette.

"The first thing you'd be told when you join the IRA is that you're going to die or go to prison," Devenny said.

In the 1970s he joined the Provisional Irish Army, the paramilitary group infamous for its guerrilla acts of civil disruption ranging from marches to violent bombings. He was just a teenager, frustrated with the political situation in Northern Ireland.

During the height of Northern Ireland's Troubles, Devenny was shot while trying to rob a bank for the IRA. He was hit three times in the arm by an automatic rifle, and the doctors cut a single long incision to remove the bullets. He was then sentenced to eight years in prison for the attempted robbery. Since that chapter of his life, Devenny has worked as a designer for Republican publications and as a poster artist for Sinn Fein. Now, 40 years later, he is one of Northern Ireland's most prolific muralists.

He has also been one of the most vocal critics of the Re-Imaging Communities project, a program by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland that supports communities across the region that want to tackle sectarianism in their neighborhood.

The city calls the program a chance for community members to reclaim their identity by using grant money to install new art pieces in the neighborhood, which includes replacing murals from past decades that commemorate paramilitary groups.

Locals such as Devenny and others who have a more intimate connection with the city's murals, however, see no benefit to what they call the whitewashing of Belfast's history.

***

These vigilante organizations formed as a response to the IRA and were active in the years of the Troubles from the 1960s to the 1990s. They were behind numerous shootings and bombings targeting Catholic nationalists and those who wanted Northern Ireland to separate from the U.K. and join the Republic of Ireland.

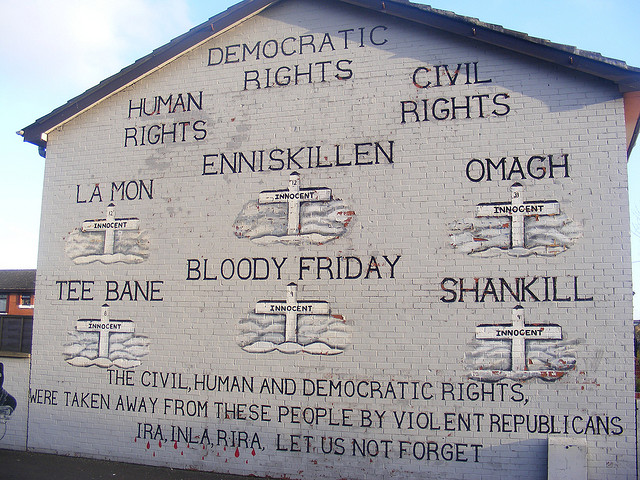

The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 brought an end to much of the violence, but it's still a long road to true integration and reconciliation between the Catholic nationalists and PUL community. In this post-conflict climate, the legacy of the paramilitaries remains strong; locals still remember the violence, the ones who fought, and the ones who were lost. Much of that remembrance is written on the walls in the form of memorial murals.

According to Program Manager Sean Keenan, the goal of the arts council is to support community members who decide they want to change the art in their neighborhood. To receive funding from the Re-Imaging project, communities are required to submit proposals of what they want to see in their neighborhood and how those changes would decrease sectarianism.

The project initially ran from July 2007 to July 2009 and was so popular that it blew through millions of pounds in funding. Now it's back, with money from the European Union.

Keenan says the program is entirely uninfluenced by local politicians. Program coordinators do not belong to any political party. Instead, Keenan says their political agenda is simply to diminish signs of sectarianism in the city.

An example of what the Art Council considers a victory for the program was the replacement of the Grim Reaper mural. Painted on a gable wall in a PUL neighborhood, the mural depicted a death-like gunman standing over the marked graves of IRA members who are still alive, under the banner of the paramilitary group the Ulster Freedom Fighters.

As part of Re-Imaging, the wall was painted over by a portrait of King William of Orange, an earlier and less sinister symbol of loyalism.

"That took years of negotiations with paramilitaries," said Ann Ward, who led the Re-Imaging program when the Grim Reaper was painted over.

In its new phase, the project aims to promote more non-mural art installations in areas outside of Belfast. But with tensions up from recent protests over the city of Belfast's decision to reduce the number of days the British flag flies over City Hall, sectarianism is at a dangerous boiling point.

"We're trying to get people to see their identity beyond the flag, beyond these images," Ward said. "Because right now it's all about fear."

***

The best way to get a sense of which way a neighborhood leans is to just look at the walls.

Protestant-Unionist areas are defined by fluttering Union Jacks; red, white and blue curbs; and the omnipresent paramilitary gunmen of the UFF, the UFV and the UDA standing tall under the symbolic Red Hand of Ulster. The tradition of murals was born out of the ornate banners once carried by the supporters of King William of Orange. They became a chief medium of propaganda when the walls were taken over by the unionist paramilitary organizations.

Catholic-Nationalist neighborhoods lack the same militant vibe. After the Good Friday Agreement, Republican muralists decided not to paint any more guns. In other words, they began to reimage themselves.

It's harder for the unionists, whose imagery has been defined by gunmen patrolling the borders of PUL territory, according to Professor Bill Rolston, director of the Transitional Justice Institute at the University of Ulster.

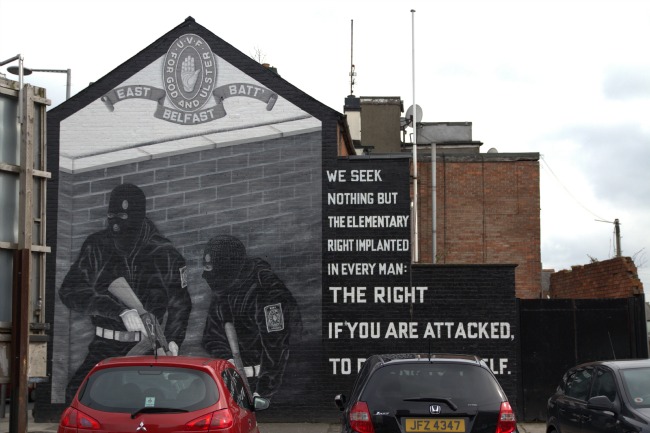

"Loyalist paramilitary groups will not give up their space," Rolston said. "They might give up some of it, but they will maintain elements of their space to say, "We're here. We're still defending the community. We defended the community for years. Don't forget what we did, and here are pictures to remind you.'"

The history of the Belfast murals is rooted in territorialism and propaganda, but Rolston warns that "there is a tendency in Re-imaging to throw out the baby with the bath water."

"What's potentially lost is politics, because even the most offensive murals were undeniably political. People were stating a political position on the wall. But now there's a sort of fear of politics, a fear of mentioning the war," Rolston said. "The trick of Re-imaging is to persuade people in these areas to still make political statements about who they are, what they believe in, what they hope for and what they fear -- without being offensive."

The decision on what is offensive, however, is tricky. Anne Ward, the Community Development Officer at the Arts Council, asserts that communities lead the projects and make the requests to remove offensive images from their walls.

"Young children walking past masked gunmen has an impact on the local community. So, the program is all about the community wanting to transform ... and creating a new Northern Ireland, " said Ward.

Community agreement means cross-party, cross-religion agreement, and the Arts Council has had successes in getting remnant paramilitary leaders to agree to paint over their militant murals.

But to Danny Devenny, it was the money the Arts Council has to give to communities willing to participate in the Re-Imaging program that's objectionable.

"Those communities need funding -- it's a carrot to bring the community along," Devenny said. "We want money to create art, to invest in our community, to allow our local artists to express themselves, but not on the basis of that we have to fill in your criteria, that it has to take out a so-called paramilitary mural. I believe the project was set up not to create peace and reconciliation between the two communities here, but to clean up the public view of unionism."

On the other side of the political spectrum is Raymond Laverty, a spokesperson for the Progressive Unionist Party, and a charismatic local leader in the PUL neighborhood of East Belfast. He doesn't deny that the militant unionist murals are more sinister than the quiet neighborhood would like, but he maintains that the Arts Council's approach trivializes the legacy of the city and replaces it with sweet nothings.

"You can't sweep 40 years of conflict under the carpet," Laverty said. "The Re-imaging program is whittling away at the historical aspects of the murals, and replacing it with what, Mickey Mouse?"

***

Most of the painted gunmen in Belfast are remnants from the Troubles, when those images reflected what was happening in the streets. But in 2011 yet another militant unionist mural went up in East Belfast, depicting two armed and masked men alongside the stark words "We seek nothing but the elementary right implanted in every man: the right if you are attacked to defend yourself."

"I thought that was really inappropriate," said a clerk who works in a post office directly across from where the mural stands along Newtonards Road.

Between the return of such images and the violence of the flag protests, it is clear that sectarian issues are still at the forefront of the city's consciousness.

But Laverty and Devenny both agree that the path to reconciliation in Northern Ireland is in reeducation, not re-imaging.

"To say that these images create a desire within young people to join paramilitaries,

it's nonsense. People don't join paramilitaries because of pictures on a wall," Devenny said. "They do it because of what's happening around them."

Devenny regularly paints with groups of children, creating murals about international issues such as racism. Laverty is a team leader at the Inner East Belfast Youth Project, where he organizes community programs for working class kids. They say investment in this type of interaction is a far more meaningful way toward reconciliation that repainting murals.

"Our young people don't understand conflict," Laverty said. "When we were young there was a killing every day. They need to talk to their elders about their history."

History is the overbearing theme in the city, one that presses on a population trying to go about their lives in a post-Troubles world. But it's that history, the nearness of it and the violence of it, that draws curious visitors to the dozens of different mural tours that run daily.

"I get so many people wanting to see the murals," said Patrick Maguire, a cab driver for the Belfast Taxi Company. "If the murals were gone, where would I take them? What would I show them in our city?"

Maguire, a Catholic republican, says he is not bothered by the militant images of unionists who are theoretically his political enemies. Similarly, Devenny holds no grudges against the images of UFF gunmen around his neighborhood, the same gunmen who once shot at him during his IRA years.

"The reason there's interest in the murals is because people come here to learn about conflict and how to create peace from hundreds of years of struggle and opposing political positions," Devenny said. "It's not the walls out there that are the problem, it's the walls in people's minds that need to come down."