Willie Mays and the basket catch — excerpt from his upcoming book

Excerpted from the book “24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid” by Willie Mays and John Shea. Available May 12 from St. Martin’s Press ($28.99, 352 pages). Reprinted with permission.

CHAPTER 6

ACT LIKE YOU’VE BEEN THERE BEFORE

The Story of a Unique and Elegant Style

“Have fun with everything you do. Be comfortable. No need to act like you’re somebody else. Be yourself. That’s good enough.”

— Willie Mays

Baseball during Willie Mays’ playing career didn’t involve bat flips. Or chest bumps. Or different celebratory greetings for every teammate. If you hit a home run, you didn’t stand in the batter’s box and admire the flight of the ball. You put your head down. You quickly ran the bases. You shook hands. You sat in the dugout.

Mays did all that. He played the game right, as it was supposed to be played in Willie’s time. But he did a lot more.

Meet the co-author

Read the story of how the book came together:

https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sports/mlb/story/2020-05-03/hall-of-famer-willie-mays-sportswriter-john-shea-new-book-24-life-stories-and-lessons-from-the-say-hey-kid

He was more than a hitter, more than a fielder, more than a runner. More than someone who suited up and played nine innings. He was more than a ballplayer. Baseball’s greatest star was baseball’s greatest entertainer.

I just feel that when you’re playing sports, you have to do more than catch the ball and throw it back in. You have to do something different. You’ve got to improvise sometimes, you’ve got to create something for the fans. Make it fun. I tried to do something different at all times.

Mays is a product of the Negro Leagues. He learned the game from his father and refined it as a teenager with the Birmingham Black Barons while surrounded by older teammates and opponents who showcased flamboyant personalities and an uptempo, all-out style of play — all of which was passed down to a young Willie, who created his own trademarks after signing with the New York Giants and working his way to big-league superstardom.

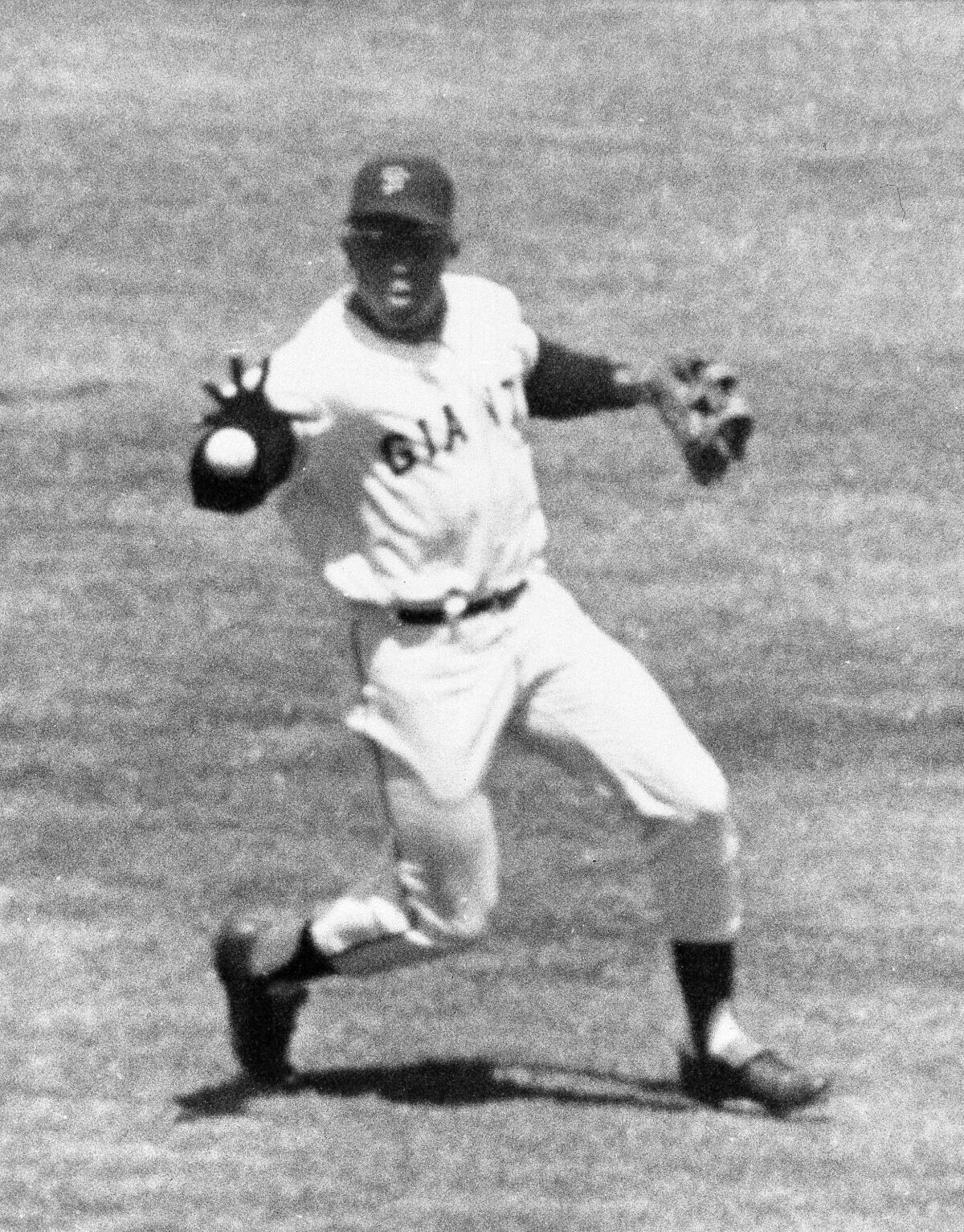

For example: For decades, outfielders were trained at an early age to raise their arms above their heads when catching a fly ball, keeping the glove hand above the bare hand, seeing the ball into the glove while closing it with both hands. Pushing the boundaries, Mays took a whole different and riskier approach. He held his glove at waist level, with his palms facing upward, and waited for the ball to drop to him.

Thus, the basket catch.

When I played, I made a game out of it. I was never uptight. The guys I played with, they couldn’t be uptight. I tried to see to that. If they were uptight, they couldn’t play like they should. If you don’t understand that, I’ll try to explain it to you a little bit more.

Baseball is a fun game. Say you go see a singer. If the guy is singing the same way every time, you’re not going to like that. You want him to mix it up. You want to walk away saying, “Oh, he changed it up a little bit.” That’s a talking point. If you’re a writer, are you going to write about the same damn thing every day? You’ve got to write so you know readers are going to enjoy reading you.

That’s all part of being entertaining. You’ve got to relax and have fun. Show me a guy who’s uptight, and I’ll show you a guy who makes a lot of errors. I was just a guy who believed in doing things the right way, the simple way.

That meant having fun. You have to have fun out there, man. If you don’t have fun, you can’t play the game. You have fun, you’ll try to hurry and get back to the field to play the next day. You have fun, now the fans are having fun. Now you’re entertaining.

To succeed and survive in baseball, as Roy Campanella would remind us, “You’ve got to have a little boy in you.” That’s Mays to a T. Hall of Fame manager Joe Torre, who grew up in Brooklyn adoring Mays, said, “Willie thoroughly looked like he enjoyed himself when he played. He changed pressure into excitement.” Legendary Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully added, “He did everything with such an air of relaxation, confidence, and laughter. Yeah, he was a little bit of a showman, but it was as if he’s saying to the world, ‘God, I love this game.’ ”

Fans grew to expect Mays to make basket catches. When fly balls were directed toward center field, fans knew they weren’t about to see anything routine. There was anticipation Mays would tap his glove, an indication to fans and a reassurance to teammates that the ball was his. There was anticipation he’d turn his left palm up to make his glove appear like a basket, with his right hand supporting the glove from underneath. There was anticipation he’d make a waist-high catch look a lot easier than it was.

Fans loved how Mays snagged the ball in a manner no one would or should teach, one of the reasons it was unwise to look away when he was on the field.

So how and why did the Say Hey Kid make basket catches?

If you normally catch the ball on your left side—as a right-hander, your glove is on your left hand and over your left shoulder—you’ve got to take time to transfer the ball from way over here on the left side to way over here on the right side.

But think about it. If you catch it down here, at the middle of your body, you’ll get rid of it more quickly. It takes less time to get the ball from glove to hand. When the ball is in your glove down here, you don’t have to try to bring your body all around before throwing it. You’re ready to throw.

The ball comes down quickly, so you’ve got to be ready, you’ve got to move your body to the ball. Your eyes are on the ball, and now you’ve got the ball in your glove. You keep going from there. You don’t try to bring the ball back up and throw. You’ve already got it where you need it.

A note to kids: Don’t try this at home, or in a game.

No, no, no. That’s just me. The correct way to catch the ball is above your head with two hands. That’s what I tell kids, over your head. Now, if you want to try the basket catch, that’s your decision. But if you get hit in the head, remember I warned you.

I’m not going to tell kids to be like me. I’ll try to help them, but I’ll tell them, “Catch the ball the best way you can. Don’t be like me, be like you.”

Mays recalls feeling the desire to entertain as far back as high school. The desire heightened in the Negro Leagues and carried over to his minor-league stops in Trenton and Minneapolis and his rookie year with the Giants in 1951. His capacity as a showman reached a whole new level as part of a life-changing twist in 1952, in the second month of what would have been his first full season in the big leagues.

On May 28, Mays lined out to shortstop Pee Wee Reese in his final at-bat of the season in a 6–2 victory at Ebbets Field. Dodger fans respectfully stood and cheered Mays, knowing he was about to report for duty to Fort Eustis near Newport News, Virginia. Mays had been drafted into the Army, joining many other players who were called into duty after the United States entered the Korean War.

While Ted Williams, Jerry Coleman, and others distinguishedly engaged in combat, most players served stateside and played on service teams, including Whitey Ford, Don Newcombe, Johnny Antonelli, and Mays. Their official duties included using their athletic talents to entertain the troops, right in Mays’ wheelhouse

“People would be talking, ‘How can he go play baseball when he’s in the Army?’ Well, it was more for morale than anything else,” said Antonelli, who pitched for another Virginia-based service team and later became Mays’ teammate with the Giants. “We would do regular duty until noon. We’d go fix up the field. At four o’clock, they would march the troops in. They were more or less stuck. They had to watch the ballgame. This is how it all happened. I think it was good for the morale. We thought we were doing something good for people.”

In effect, Mays wasn’t in the big leagues, but he still was able to delight people through baseball. He missed the rest of the 1952 season and all of 1953 but remained in his element, on the diamond showcasing his extraordinary skills and style. If he was going to get the opportunity to play ball while serving in the military, he vowed to make the best of it.

We played every day. I actually played seven days a week, for Fort Eustis and a team that played weekends in Newport News. In those two years, I got stronger. My power grew. I went in at 155, 160 pounds and came out at 180. I didn’t have time to relax, but I wanted to learn something that was different, give ’em something to write about, and I tried catching the ball different ways.

The basket catch, I perfected that when I was in the Army. Bill Rigney, one of our infielders with the Giants, caught popups that way. I practiced it, first just messing around and then using it in games. I wanted people to know this was a new game. When I came out of the Army, Leo (Durocher) said you could do it, but don’t miss the damn ball. I missed two. Ten years apart. Ernie Banks in the Polo Grounds and Donn Clendenon in Pittsburgh.

Fred Lovell was in the Army with Mays and recalled his old buddy was magnetic not just on the field but off.

“We took basic training together, about a six-week deal,” Lovell said. “Willie was a hell of a nice guy and got along with everybody in the company. He would always come out and put a little show on for everybody, jive ’em up a bit. One time, he came out dancing with one boot untied, his pant leg up a little bit, and his hat turned sideways. Well, we had a new master sergeant come in, and the other sergeants said he’d give us hell when he got there. I actually knew him well before the Army, but he didn’t know Willie and wasn’t used to him.

“So when Willie comes out dancing around and putting on a show, the sergeant grabs him and throws him down. All the other cadets yelled, ‘Lovell, get your friend off him, get your friend off him.’ I tapped the master sergeant on the back and said, ‘Willie’s the only friend I have in the company, Sergeant, get off him.’ He got off him, and it was all over with. Willie could’ve whipped the sergeant’s rear end. He was in first-class shape when he was in the Army, but he didn’t want to fight. After the sergeant got to know Willie, they were the best of friends.”

Antonelli recalls Mays’ on-field exploits. Before emerging as a five-time All-Star with the Giants, Antonelli honed his skills with his service team.

“I just thought he was a great ballplayer, a great guy who deserved everything he got in the game,” Antonelli said. “I first saw Willie when we faced each other in the Army. It was just one game. I was at Fort Myer, Virginia, and he had just gotten in there. Our team was pretty good. We played some good ballclubs. We played Whitey Ford’s team, Harvey Haddix’s team. We beat these teams.

“I went 42–2 in two years in the Army. It was like my minor leagues. It got me ready for the big leagues. As it turned out, I got traded from the Braves to the Giants before the 1954 season and always wondered if Willie said something to get me to the Giants. I never did ask him that question.”

Mays said it didn’t happen, adding he was too young at the time to suggest such a transaction. Regardless, the trade significantly benefited the Giants, who swept Cleveland in the 1954 World Series. Not only was Mays the batting champion and National League MVP but Antonelli was the league’s premier pitcher, winning 21 games and posting a league-low 2.30 ERA. He won Game 2 of the World Series and saved Game 4.

You’ve got to serve your country, and that’s what I did. They called on a lot of players to do different things. I guess I was blessed to get to do what I did at Fort Eustis. I didn’t rebel. They wanted me to be an entertainer for the troops, and that’s what I did. We had some good teams in there, a lot of good players, a lot of major-league players.

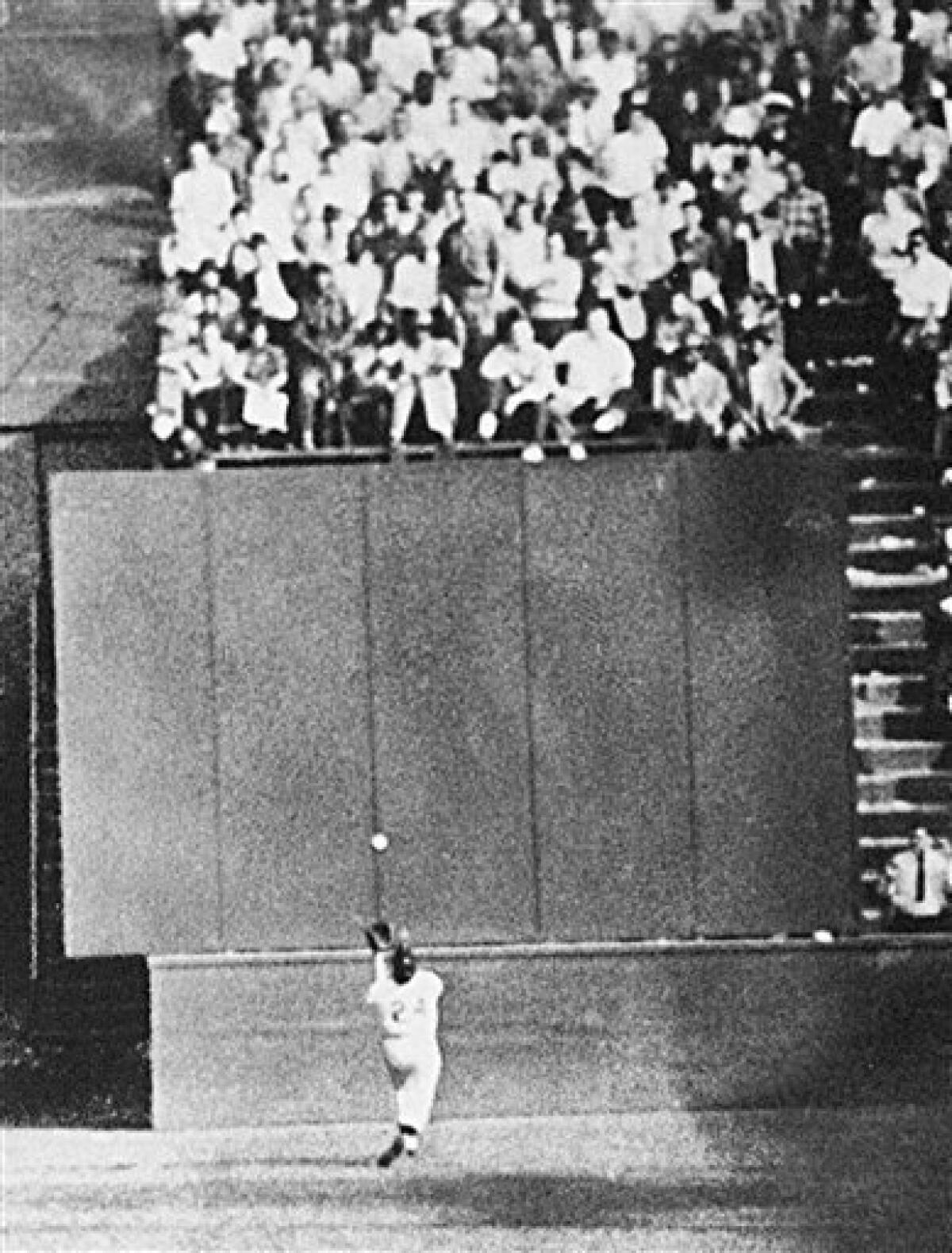

Mays’ work refining the basket catch in the Army helped him make his famous World Series catch, the one off Vic Wertz’s bat in the 1954 opener. It was no ordinary basket catch because his back was to the plate in deep center field at the Polo Grounds, but his palms were up and the ball came down in his glove.

I messed around with all that kind of stuff. I could catch it up high, at my waist, one hand, two hands, behind my back, between my legs. I practiced that in spring training, catching the ball between the legs. That’s how I got in shape, doing different things like that.

I’m not bragging. I never bragged. I just played the game, and every once in a while, I’d do something to keep the guys laughing. I would teach the guys to catch it behind their back, but I was scared to let them do it between their legs because they had no cup on.

The point is, you practice all these things, it becomes easy. You talk about the basket catch, I could do that because I practiced it. The entertainment comes with doing things the right way.

Rigney might have caught some infield popups with his glove turned around, but Mays was making those catches hundreds of feet from the plate. He popularized the basket catch and made it one of the most endearing qualities on his road to 7,095 outfield putouts, the most in history.

“Where do you think he learned the basket catch? He saw me,” Rigney said with a wink decades later. “I never dropped one. Pitchers hated it. One said, ‘If you ever drop one, I’m comin’ after ya.’ At Seals Stadium, one hit me in the chest but bounced into my glove.”

Of course, it’s not for everybody, even Angels center fielder Mike Trout, a generational talent who has been called a modern-day Mays (or Mickey Mantle) for his five-tool proficiency.

“I tried it during batting practice. It’s pretty tough,” Trout said. “It’s amazing Willie was able to do that, pretty impressive. It was great to see his personality. That’s the way the game’s going now.”

Part of Mays’ charm was his daring willingness to do things others couldn’t or wouldn’t. They were usually simple things but pleasing to the eye, such as running so fast that his cap would fly off or throwing sidearm from all regions of the outfield.

They thought I used to knock my cap off. Nah. Eddie Logan, our equipment manager, used to give me one size too small, and when you look up, it’s going to fall off anyway. People like that. They love all that kind of stuff. They want to see the hat fall off. No problem. I go back, pick it up, and put it back on.

I threw sidearm only when nobody was on base. If you look at film and I’m throwing sidearm, nothing is happening in the game. But if I have to make a throw to get a guy out, I go over the top because you want the ball to go straight. When you throw sidearm, the ball spins sideways.

Mays’ flair and elegance were worshiped throughout the years, but he was more about substance than show. Flashy visuals aside, he seemed to always do the right thing, always be in the right position, always know what to expect. He had a one-of-a-kind style, but his actions were calculated because what mattered most was winning. He knew all eyes were on him, and while he would entertain with panache, he’d make sure to play with purpose.

“The Giants had five Hall of Famers, and we knew anytime we went into a town, the newspaper would say ‘Willie Mays and Company,’” former teammate Felipe Alou said. “Everyone knew Willie was the guy, and he knew he was the guy. Some players probably didn’t like that a whole lot, but Willie was leadership by example, a very responsible performer who played every day, hustled every day, and produced every day. We were proud of the company.”

Fans flocked to ballparks around the country to see Mays play. In the 1960s, the Giants led the National League in annual road attendance eight times and again in 1971, Mays’ last full season on the West Coast. In his fourteen full seasons in San Francisco, the Giants were first or second in road attendance thirteen times. In New York, they ranked second in 1954 and 1955, Mays’ first two years out of the military.

“He was always a kid with that high voice and excitement level, always with a boyish enthusiasm. The Say Hey Kid and rightly named,” said Roger Angell, the poet laureate of baseball, who has composed wonderfully vivid essays since the mid-twentieth century, especially for The New Yorker. “I can still see (Joe) DiMaggio with his long strides, never hurried, and I never remember him falling down or lunging for something. He was remarkable. But Willie would run faster and farther and make a great play. He engaged you. You’d go ‘wow.’ You’d never go ‘wow’ with DiMaggio, who had grace and style but kept you at a distance. Willie had tremendous speed. Deadly hitter. Great fielder. He caught the ball a new way, and all around the country, kids were trying basket catches.”

Broadcaster Bob Costas recalled Mays as naturally stylish but not at the expense of efficiency and effectiveness.

“There are some athletes who go beyond talent, beyond craft, and they turn their game into an art form,” Costas said. “Although the statistics attest to their greatness, the real abiding thought is just the images of watching them play.

“Instantly, if you walked into a ballpark and didn’t know anything about baseball, your eye would go to Willie Mays. There was something so magnetic and so charismatic and so stylish and so artful about him that statistics only support him. You didn’t have to look in the record book. You could feel it.”

Or, as former teammate Joey Amalfitano said, “You never knew what the hell he was going to do. Movie stars have scripts. This guy had no script. You know what he had? Instincts. They were off the charts to perform like he did. Frank Sinatra had his own style. Well, this guy had his own style. Everything he did was poetry in motion. It was beautiful watching him hit a triple. You could take it to the bank that hat was falling off. No one had the style Willie had.”

Mays’ explanation:

I was me at all times. I don’t try to tell guys to be like me. If a guy comes to me, I’ll try to help him. But he’s got to do it on his own.

Go deeper inside the Padres

Get our free Padres Daily newsletter, free to your inbox every day of the season.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.