Visceral Pain

Recently I attended a PD lecture presented by my colleague Daniel Zwolak, who is a APA titled Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist. His lecture was on the clinical signs of visceral pain. It was a great opportunity to reflect on my clinical reasoning process and understanding of specific non-musculoskeletal pain conditions. Inspired by his lecture, I have chosen to write this blog on some of the more common conditions which may present to a physiotherapy private practice clinic.

Before we discuss individual conditions I want to touch on the features which raise suspicion during the subjective examination. These may include:

- No associated mechanism of injury, no definite trigger or clear explanation for the pain.

- Poorly localised pain.

- Non-mechanical behaviour.

I often refer back to Maitland's vertebral manipulation for guidance on assessment and clinical reasoning. When looking back through the text this time I noticed two major points...

Make features fit

"The manipulative physiotherapist will tell the patient that the problem is like a jigsaw puzzle, and it is her job to make 'all the pieces fit'. She needs his help to do this, and it is her ability to communicate that makes the difference between her being successful in helping him with his problem or not" (Maitland, Hengeveld, Banks, & English, 2005, p. 57).

The first part of clinical reasoning begins in the subjective examination when we try to determine the source of the patient's symptoms. It is during this time when the therapist directs questioning to the behaviour, location, severity, nature and cause of the problem. We develop a list of the possible sources for any part of the patient's symptoms which requires examination. This includes the underlying structures, structures which refer to the area, and the regions above and below the area of the problem.

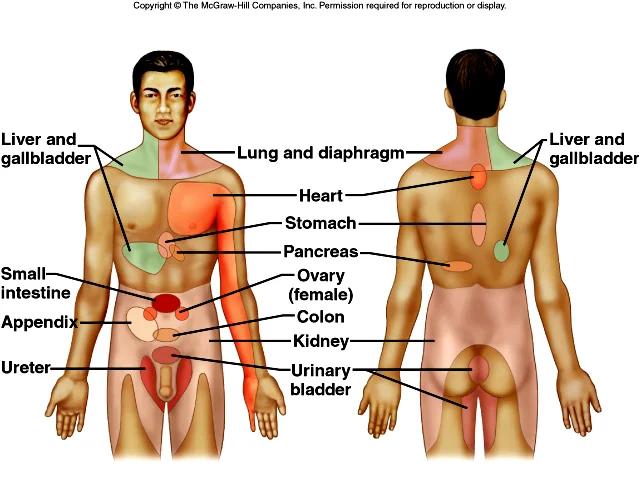

If we look at the image below, which depicts the referral patterns for visceral pain, it becomes clear that differentiating between musculoskeletal, visceral and neural pains can be complicated if the only tool we use is the body chart. There is a large degree of overlap in symptom distribution in a patient presenting with neck, back and pelvic pain.

Courtesy of Google Images

Listen and believe

"In assessment, listening and perceptive questioning are essential to gain information that cannot be revealed by any other form of examination" (Maitland, Hengeveld, Banks, & English, 2005, p. 55).

"It is important for the physiotherapist to realize that the patient is able to 'feel' far more than the manipulative physiotherapist can ever determine by examination - his body can inform him of very fine changes, and it is her responsibility to listen and acknowledge" (Maitland, Hengeveld, Banks, & English, 2005, p. 57).

Patient's presenting with non-musculoskeletal conditions will often lack a clear trigger or mechanism for onset. Their pain doesn't have a clear mechanical aggravating pattern. Often the pain may follow a different pattern such as a 24 hour pattern or be worse after events such as eating (in the case of cholecystectomy). We need to ask our special questions about other symptoms, past medical history, medication use and red flags.... which often leads us to question if the source of the problem is perhaps a visceral pain or another medical condition.

If at the conclusion of the subjective examination a non-musculoskeletal condition is suspected, a physical examination should still be completed to an appropriate/safe extent to confirm the hypothesis, to rule out joints and structures and to evaluate the effect of movement, testing, palpation on the problem.

Below are some of the possible visceral conditions which may present as neck, back, chest and pelvic pain.

Chest pain

Chest pain can originate from musculoskeletal, pleural, and tracheal inflammation. "The lung parenchyma and small airways contain no pain fibres" and therefore cannot be a source of pain (Pryor & Prasad, 2002, p. 7).

- "Pleuritic chest pain is caused by inflammation of the parietal pleura and is usually described as a severe, sharp, stabbing pain which is worse on inspiration. It is not reproduced by palpation" (Pryor & Prasad, 2002, p. 7). Pulmonary conditions causing chest pain include pleurisy, pulmonary embolus, pneumothorax, and tumours.

- "Tracheitis generally causes a constant burning pain in the centre of the chest, aggravated by breathing" (Pryor & Prasad, 2002, p. 7)

- "Musculoskeletal (chest wall) pain may originate from the muscles, bones, joints or nerves of the thoracic cage. It is usually well localized and exacerbated by chest and/ or arm movement. Palpation will usually reproduce the pain" (Pryor & Prasad, 2002, p. 7-8). Musculoskeletal conditions may include rib fracture, muscular or articular dysfunction, costochondritis, and neuralgia.

- "Angina pectoris is a major symptom of cardiac disease. Myocardial ischaemia characteristically causes a dull, central, retrosternal, gripping or band-like sensation, which may radiate to the arm, neck or jaw" (Pryor & Prasad, 2002, p. 8).

- "Pericarditis may cause pain similar to angina or pleurisy. "(Pryor & Prasad, 2002, p. 8)

- Mediastinum pain can be a symptom of dissecting aortic aneurysm (DAA), oesophageal pain, or mediastinal shift (caused by pneumothorax or large pleural effusion). DAA is described as sudden onset of severe and poorly localized central chest pain and can be caused by trauma, atherosclerosis or Marfan's syndrome.

Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis refers to inflammation of the kidney(s). It is most commonly a bacterial infection. Patients present with fever, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, and may also present with dysuria, and/or increased urinary frequency or urgency.

The tables below highlight the clinical presentation of cystitis, pyelonephritis and urosepsis. The grading of severity is a helpful way to interpret the variability in symptoms which patients may present with. The second table outlines which risk factors have been identified for developing a urinary tract infection (often a precursor to pyelonephritis).

(Johansen, Naber, Wagenlehner & Tenke, 2011, p. 266)

(Johansen, Naber, Wagenlehner & Tenke, 2011, p. 267)

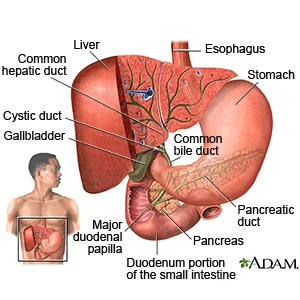

Cholecystitis

Courtesy of Google Images

- Inflammation of the gall bladder.

- Usual cause is gallstones.

- Females: Males 3:1, usually > 40 years of age.

- Right upper quadrant or epigastric colic that either persists or escalates over 12-24 hours.

- Low grade fever, tachycardia, and marked right upper quadrant tenderness.

- Pain often radiates to the right scapula or interscapular area.

- 25% of patients have a palpable distended gallbladder.

- Symptoms often following large or fat-rich meals, which can wake the patient during the night.

- Other symptoms include chills, malaise, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.

- The examiner must remember to question the patient about orange-tea–coloured urine or clay-coloured stool, which would raise the suspicion of a common duct obstruction.

- "The classic Murphy sign, the abrupt inhibition of inspiration with palpation directly over the gallbladder fossa, is commonly seen. Abdominal wall guarding or rigidity must raise the suspicion of gangrenous cholecystitis or perforation" (Elwood, 2008, p. 1244).

Conditions masquerading as sports injuries

This is diverting from visceral pain specifically but I thought it was worthwhile to refer to Brukner and Khan (2006), a popular text for clinical sports medicine and review the conditions they highlight for consideration.

- Bone and soft tissue tumours

- Osteosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, synovial chondromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis, rhabdomyosacroma, osteoid osteoma, and ganglion cyst.

- Such tumours are more common in the younger patient, their pain is aggravated by activity and XRAY may reveal a 'moth-eaten' appearance in the long bones.

- Other signs of malignancy or infection include night pain, waking in the night with pain, loss of appetite, loss of weight and fever.

- Rheumatological conditions

- Inflammatory monoarthritis, inflammatory polyarthritis, inflammatory low back pain, and enthesopathies.

- Clinicians may question for inflammatory conditions when patients present with multiple joint pains, with atraumatic swollen and painful joints, more prominent morning stiffness, and night pain.

- Disorders of muscle

- Dermatomyositis, polymyositis, and muscular dystrophy.

- "Dermatomyositis and polymyositis are inflammatory connective tissue disorders characterised by proximal limb girdle weakness, often without pain" (Brukner & Khan, 2006, p. 36).

- Endocrine disorders

- Dysthyroidism, hypercalcemia, hypocalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, Cushing's syndrome and acromegaly.

- Endocrine disorders may lead to deposition of calcium pyrophosphate in joints. In such cases patients present with acute pseudogout or a polyarticular inflammatory arthritis (Brukner & Khan, 2006).

- Diabetes is a consideration in patients with septic arthritis or frozen shoulder.

- Vascular disorders

- Venous thrombosis, artery entrapment, and peripheral vascular disease.

- Pain is often worse with activity and swelling may occur. Consider questioning patients for a history of recent surgery or travel. Vascular claudication is another symptom to consider in vascular disorders.

- Genetic disorders

- Marfan's syndrome and Hemochromatosis

- Granulomatous diseases

- Tuberculosis and sarcoidosis.

- Infection

- Osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and shingles.

- Symptoms may include bone pain, pain worse at night, pain worse with activity, reactive joint effusion,

- Regional pain syndromes

- Complex regional pain syndrome type 1 and fibromyalgia.

That list is extensive! I don't know a lot about all of these conditions and they aren't managed by physiotherapists. Sometimes patients present with these co-morbidities and it is important to understand how they may impact on your treatment of a problem. But aside from that, at least it helps me to keep an open mind when thinking what else can be contributing to the problem.

After reading this information I would encourage you to remember that it is not common for patients with visceral problems to primarily seek help from physiotherapists. But one thing many of these conditions have in common is pain and pain with movement and therefore they might seek help from a physiotherapist first. We need to be prepared with the right questions and equipped to recognised the signs of non-musculoskeletal conditions. Don't hesitate to refer back to the GP (or in worst case emergency) when the features don't fit, when patients don't follow the patterns we recognise and when they don't respond in the predictable way.

Sian

References

Bjerklund Johansen, T. E., Naber, K., Wagenlehner, F., & Tenke, P. (2011). Patient assessment in urinary tract infections: symptoms, risk factors and antibiotic treatment options. Surgery (Oxford), 29(6), 265-271.

Brukner, P., & Khan, K. (2006). Clinical sports medicine. McGraw Hill.

Elwood, D. R. (2008). Cholecystitis. Surgical Clinics of North America, 88(6), 1241-1252.

Maitland, G., Hengeveld, E., Banks, K., & English, K. (2005). Maitland's Vertebral Manipulation 7th Edition (pp. 445-458). Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann.

Pryor, J., & Prasad, S. (2002). Physiotherapy for respiratory and cardiac problems Churchill Livingstone.

Sikandar, S., & Dickenson, A. H. (2012). Visceral pain: the ins and outs, the ups and downs. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care, 6(1), 17-26.

Van Tulder, M., Becker, A., Bekkering, T., Breen, A., Gil del Real, M. T., Hutchinson, A., ... & Malmivaara, A. (2006). Chapter 3 European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. European Spine Journal, 15, s169-s191.