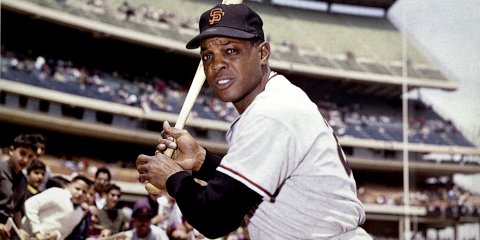

Willie Mays, as most baseball fans know, is one of the game's most iconic figures.

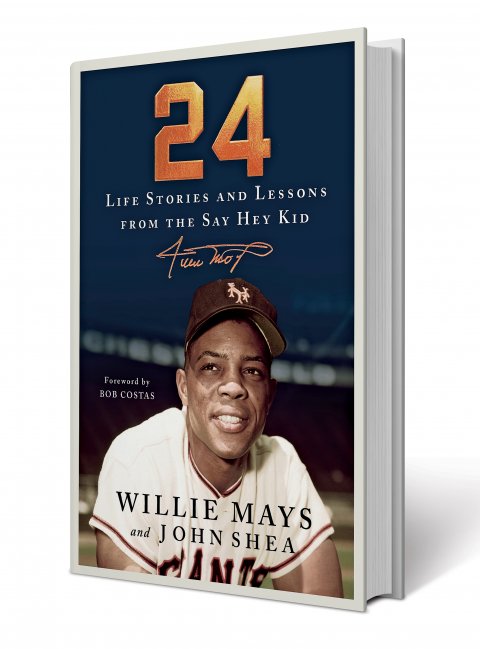

For 22 seasons, he was the center fielder for the New York Giants, San Francisco Giants and, at the end of his career, the New York Mets. Among his accomplishments: Mays hit 660 home runs (No. 5 on the career leaders list) and was a 24-time All-Star—more than the number of seasons he played due to a window when the games were held twice a year. He is, of course, in the Baseball Hall of Fame. In his new book, 24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid, written with award-winning baseball writer John Shea of the San Francisco Chronicle, Mays shares tales from his life in sports and what he's learned. In this excerpt, the authors discuss how Mays approached his All-Star appearances and how the games have devolved over time.

One of the beauties of All-Star Games during Willie Mays' career was the sense of pride and unity displayed by players from different teams joining together to take on the rival league, an opportunity to show their talents to wider audiences on a national stage. Mays absolutely loved playing in All-Star Games and treated them as if they were the playoffs, not exhibitions. He went all out and played with boundless energy and joy.

Willie Mays: That's what the All-Star Game is all about, isn't it? That's what I always thought. It was for the fans, and they wanted me to play nine innings every game, so that's what I did. Sometimes 10. I wanted to win. I thought winning was the key to the whole thing.

Mays played in 24 All-Star Games, each one from 1954, his first year out of the Army, to 1973, his final season, and the National League's record in those games was 17–6–1. Nobody was more spectacular than Mays, whose 23 hits and 20 runs are All-Star records that aren't expected to be broken.

Warren Giles was the National League president through most of Willie's career and held clubhouse meetings before every All-Star Game to preach the importance of winning and encourage players to take pride in rallying against their American League foes. Mays accepted the challenge.

Mays: This is what people told me: "The American League is killing us, man." I said, "Uh-uh. I don't know about anybody else, but I'm going to play nine innings. We're going to change that." Then Hank (Aaron) and all the other guys came in. Frank Robinson, (Roberto) Clemente, and we started winning games. They felt the same way. I wanted to play every inning until the game was decided one way or another.

Aaron remembers the pregame speeches. His first All-Star Game was 1955, a year after Mays' All-Star debut: "I didn't start the game. I don't think Willie started. I don't think Stan Musial started, but I remember Stan Musial hitting a home run in the 12th inning. From that point on, we started winning ball games, and we caught up with the American League, passed them, and were able to stand on our own. I think one reason for that, and let's face it, the American League was so far behind in trying to bring in black ballplayers. The National League was always ahead of them in using black talent."

In those days, not every All-Star felt entitled to play. Making the team was privilege enough, and starters played much longer than they do nowadays. All-Star Games in 1961 and 1966 lasted 10 innings, and Mays started and played until the bitter end in both. Years later, All-Stars found themselves bowing out after two plate appearances, leaving the ballpark well before the final pitch.

With the advent of free agency in the '70s that led to rampant player movement between the leagues and interleague play in the '90s that diminished the league-versus-league rivalry, All-Star Games lost some of their luster for the new generations of players.

The luster never was lost on Mays, who has more All-Star Games to his name than seasons played because of a four-year stretch in which games were played twice a year (from 1959 through 1962) to generate more revenue for the players' pension fund. Mays hit for the cycle in 1960—a single, double and triple at Municipal Stadium in Kansas City and two days later a homer and two singles at Yankee Stadium.

The homer was off Yankees ace Whitey Ford, which was nothing new. Ford is a Hall of Famer, 236-game winner and five-time World Series champion, but Mays was his Kryptonite. Mays collected hits in his first six All-Star at-bats facing Ford in 1955, 1956, 1959 and 1960. Two homers, a triple, and three singles.

Mays: I loved to hit off Whitey. I liked Whitey. He was a good pitcher. He won 20 games a couple of times. You just see the ball very well against certain pitchers. Sometimes you can't explain it.

An explanation wasn't required.

"I remember Whitey coming back after All-Star Games saying, 'I don't care what I throw, he hits it,'" Yankees second baseman Bobby Richardson said. "Willie was the show of seemingly every All-Star Game."

Ford finally got Mays out in the 1961 game hosted by the Giants, albeit not necessarily by following the rules. The day before the game, Ford and Yankees teammate Mickey Mantle played golf at San Francisco's Olympic Club, guests of Giants owner Horace Stoneham, and then went on a shopping binge and put it on Stoneham's bill.

"We play golf and then spend about $600 on sweaters and shirts and golf balls and charge it to Horace," Ford said. "We're about to [repay Horace and he] says to me, 'I tell you what, if you get in the game tomorrow and face Willie and get him out, we'll call it even. But if he gets a hit, you owe me $1,200.' I said, 'Sure, I'll bet you.'

"So in the first inning, I get the first two outs, and then Willie's up and hits two foul balls about 500 feet.

"I say to myself, 'This is not an official game. They're not watching me closely. Let's screw with the ball a little.' So I throw him a spitball, and it starts right at him. Willie about falls down. He thinks the ball is going to hit him, and the umpire says 'strike three.'

"The inning ends, and Willie walks by me and says, 'What the hell was that you threw?' Mickey's coming in from center field clapping, and Willie says, 'What's that crazy SOB clapping for?'

"We ended up getting all the sweaters, hats and golf balls, no charge."

Mays remembers the story and laughs about it. It was his final All-Star at-bat against Ford, making him 6-for-7. Throw in the 1962 World Series (4-for-9), and Mays was 10-for-16 against the Yankees' lefty, an astounding .625 batting average.

Mays: That's a true story. Whitey finally got me out, and Mickey's blabbing out there. Nobody told me why at the time. Finally, Elston Howard said, "You know why?" "No, what's wrong with that SOB?" He said, "They had a bet. They saved $1,200." Mr. Stoneham told them if they got me out one time, he'd pay for all the stuff at the Olympic Club. Whitey got me one time.

Mays impacted practically every All-Star Game he played. He started a record 18 of his 24 games, including 14 straight. He said he came to win, and he usually did. To this day, no one has more All-Star hits, runs, steals, multiple-hit games, extra-base hits, total bases or triples than Mays, who took pride in showcasing his talents and helping the National League win significantly more than it lost.

Mays: All-Star Games were important to me. I loved them. I was fortunate to play in a lot of them and play just about every inning. A few of us stayed in the game until it was decided. A lot of times, that was in the eighth or ninth inning. For me, if you're not in the game, it's hard to have a feeling for it. I was just honored to go and represent the National League and play to win. That was true for a lot of us.

→ Excerpt adapted from 24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid by Willie Mays and John Shea, published by St. Martin's Press.

Q&A: Willie Mays

by Hank Gilman

Why was the book important?

Mays: You want to make sure kids do the right thing and grow up to do the right thing so their kids can do the same. That's the message we wanted to send. It can be through baseball or outside of baseball. This is for the kids. People took care of me when I was young, and I wanted to do this for the next generations.

How important were All-Star Games when you played because there's talk nowadays about All-Stars not caring so much?

Mays: I don't see that. I enjoyed my time in All-Star Games. It was important for us to win so I wanted to play the whole game. When I came along, they told me the American League was winning every year, so we came in and tried to change that.

Should we even have an All-Star game anymore?

Mays: It's good for teams to take a break during the season, give the guys the time off. Fans like the game. They like the leagues coming together for a game. You see guys you don't always see. It's a fun time, man. It's for the fans.

Would you compare some of today's players with players in your era?

Mays: I don't like to put pressure on the guys today. It's a whole new group. They're taking after the guys before them, and then the next guys will come along. All the guys can play. It's not right to compare any of these guys to us. Let them be who they are.