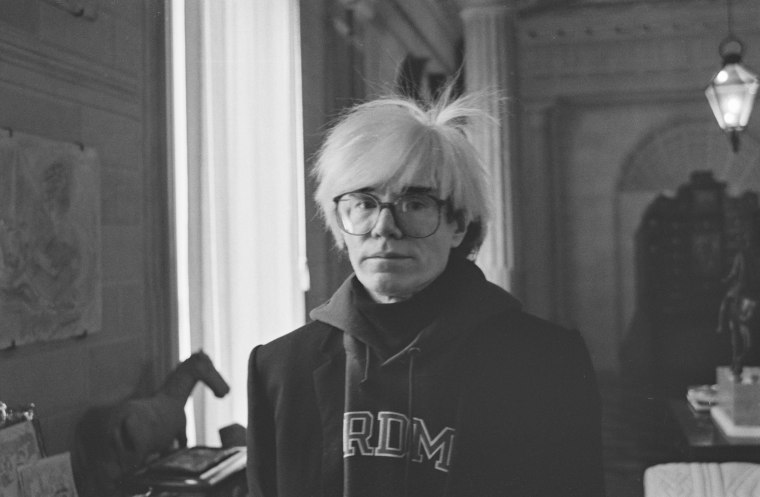

During his prolific career, Andy Warhol was a pervasive, yet elusive, art world icon who constantly reinvented himself. After his death, he’s remained an enigmatic figure, inspiring numerous documentaries, biopics and fictionalized portrayals — all looking to communicate some truth about the artist.

Netflix’s “The Andy Warhol Diaries” — directed by Andrew Rossi and executive produced by Ryan Murphy — is the latest addition to that body of work. The six-part docuseries is based on and takes its name from Warhol’s dictated memoirs, which were published posthumously in 1989. From the mid-1970s until his death in 1987, Warhol relayed the diary entries over the phone to the journalist Pat Hackett, detailing everything from his expenses to his love affairs and the guest lists of exclusive parties.

As the series argues, the diaries are a rare window into the artist’s true self: Warhol in his own words rather than those of the persona, or personas, that he sold for mass consumption. Rossi uses them, along with archival materials and interviews with Warhol’s contemporaries and acolytes, to reveal the humanity behind the icon.

The final product is an intimate portrayal, littered with keepsakes from the artist’s life and featuring his voice, constructed with artificial intelligence, reading the often heartbreaking diaries.

Rossi, who came of age in the decade in which Warhol produced his final works, said he was inspired to explore the often-overlooked side of Warhol by focusing on the artist’s private life and romantic relationships.

“Growing up as a bisexual man, in a world that was very homophobic in the 1980s,” Rossi said of himself, “Andy was almost like a safe space, and he gave permission to be who you wanted to be.”

Rossi said he decided to option “The Andy Warhol Diaries” in 2011, amid the controversy over legalizing same-sex marriage, because he “thought something in Andy’s story might shed some light on what it would mean to feel like you can have a long-term relationship, like your identity is validated.”

Taking aim at long-held notions about Warhol’s sexuality — which the artist himself perpetuated, including the idea that he was asexual — Rossi explores how the pop art icon was in fact shaped by the great loves of his life.

The Warhol mystique

The first episode of “The Andy Warhol Diaries” briefly touches on the artist’s Catholic upbringing in Pittsburgh and his early career as a fashion illustrator in New York, before swiftly moving into the glory days of The Factory, the art studio Warhol founded in 1962, and his shooting by the radical feminist Valerie Solanas in 1968.

Whereas most works about Warhol focus on this time period — when The Factory was the cultural center of New York and Warhol introduced the world to works like the “Campbell’s Soup Cans” series — Rossi is more concerned with how this period became a catalyst for Warhol’s first, and arguably most, formative romance: with Jed Johnson, the future interior designer.

Warhol met Johnson, who had recently moved to the city with his twin brother, Jay, after he was hired to do odd jobs at The Factory. That same year, Solanas — who said after the shooting, “He had too much control over my life” — shot and critically injured Warhol at The Factory. The incident debilitated Warhol physically and creatively, prompting Johnson to move in with him and become his caretaker, and then eventually his long-term partner.

Although the couple preferred to keep their private life separate from the goings on of The Factory, Jay Johnson, who is interviewed in the series, said that was a product of their dynamic rather than something incomplete or hidden about the relationship.

“It was a complicated relationship, but a very loving one,” he told NBC News. “I don’t think that [Warhol] really was hiding his sexuality, and I don’t think that he ever thought that it interfered with his career. He was pretty much able to be out, in his way, and not worry about it jeopardizing him.”

“If you were at The Factory, you certainly were aware of his private life,” he added. “The people that were around him were predominantly homosexual, and so it was not an atmosphere of repression at all. It was a lot of drugs and a lot of sex and a lot of partying.”

Because of Warhol’s own claims that he was asexual, it’s been speculated that his relationships were chiefly platonic, if not merely exploitative — something the series refutes.

“The idea that Andy remained a sort of enigma, he enjoyed that,” Jay Johnson said. “He enjoyed the idea that he was considered a voyeur and that he was considered asexual. That was his mystique.”

While Warhol’s asexuality was in some ways a myth, according to Jay Johnson, in other ways it spoke to Warhol’s discomfort around his sexuality.

“Andy certainly wasn’t asexual, but he was close to it,” he said.

Warhol wasn’t shy, however, when it came to inquiring about the love lives of other people, Jay Johnson said.

“He was so curious about other people, and he loved to provoke you into talking about your sexual life: who your boyfriends were and what you were doing,” he explained. “He really got off on it. He had a lot of fun teasing people in that way.”

Eventually, Warhol and Johnson split after 12 years together. Though, as the series portrays, the profundity of that relationship would continue to echo through the artist’s life and work.

As the relationship unravels on screen, spurred on by Warhol’s nights at Studio 54 and his relationship with Victor Hugo, the longtime lover of the designer Halston, there’s a palpable sense of emptiness and regret attached to Warhol’s hedonism.

When Rossi was sifting through archival materials — including the nude polaroids that Hugo collaborated on, which would inspire Warhol’s “Sex Parts” series — and collecting interviews, he learned that Jed Johnson had attempted suicide twice during this period.

“All of those things came together to paint this picture that is analytically elucidating,” Rossi said. “But also you’re there with Andy: You’re going to Studio 54 with him. You’re in the middle of that relationship, and it’s emotional.”

An icon's final era

Through the Jed Johnson episodes, “The Andy Warhol Diaries” succeeds in showing a more amorous side to the artist. But, in some ways, that comes toppling down as the series moves into Warhol’s final decade, which it portrays as defined by heartbreak, illness and death.

“Andy had a tendency to just cut people out of his life when he was hurt or disappointed or they didn’t serve the purpose that he needed. I think that he was heartbroken and that he was desperately trying for something,” Jay Johnson said of Warhol’s split with his brother and the immediate courtship of the Paramount executive Jon Gould.

Warhol largely doesn’t mention Gould, who was closeted throughout their romance, by name in his diaries. But his presence is felt in the archival footage, interviews and Warhol’s art from the era, which are detailed in the series’ later episodes.

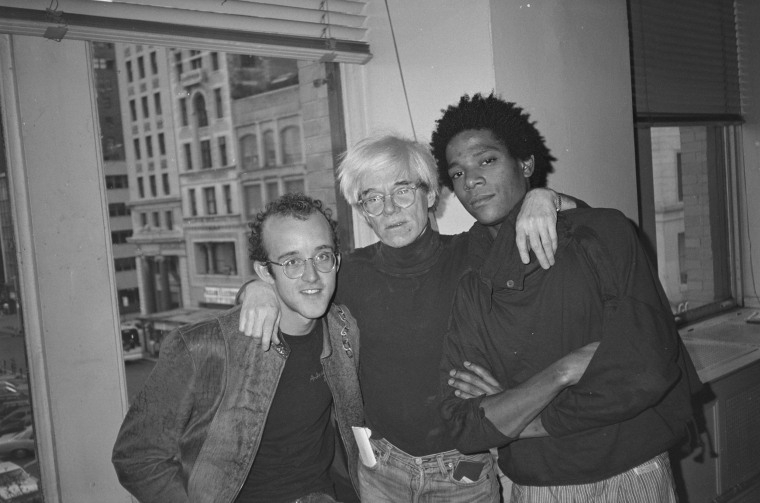

In addition to being the subject of one of Warhol’s portraits — which garnered him commercial, if not critical, success later in his career — Gould appeared symbolically in many works. During Warhol’s friendship and two-year collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat, which is also heavily explored in the series, the older artist frequently used the Paramount logo in paintings.

Amid Gould being diagnosed with and, in 1986 at age 33, dying of AIDS, both the anxieties of the era and Warhol’s sense of loss are apparent in his increasingly abstract paintings.

Like the art, and the artist himself, the series changes as it leaves behind the ‘60s and ‘70s and settles into Warhol’s final decade. Although he dedicates little time to discussing Warhol’s early output, Rossi lingers over these late works, including his final series of paintings, “The Last Supper,” which he completed a year before his death.

“‘The Last Supper’ series … has an expression of Andy’s anxiety around HIV/AIDS — and the figure of Christ as both a judge and someone with mercy — in a moment where Andy’s internalized homophobia and his shame was in so much of what he describes in the diaries,” Rossi said. “You really feel his pain there.”

Although “The Last Supper” along with the “Shadows,” “Rorschach” and “Camouflage” series have often been disregarded in documentaries and scholarship, Rossi said they were essential to the story he wanted to tell through Warhol.

“They were part of this era when he was seen as a has-been, which is connected to a homophobia around him being somebody who was too queer for mass American media — especially during the Reagan ‘80s and the HIV/AIDS era — when people really viewed queerness as something that was a threat to them,” he said.

All six episodes of “The Andy Warhol Diaries” are available on Netflix.