Giuseppe Verdi: Uniting Italy With Music

Born alongside Italy’s press for nationhood, Verdi’s operas provided Italians with the music that expressed the passion for their cause and became an important part of Italy’s national identity.

A writer named Gianrinaldo Carli told a story that became famous in Italy in the 1760s: A stranger walks into a cafe in Milan, and the patrons ask if he is a foreigner. No, he replies. Then you must be Milanese, they say, and once again he replies in the negative. Scratching their heads, they tell him that if he is not Milanese, he must be foreign, to which he replies, “I am Italian ... and an Italian in Italy can never be foreign.”

In the 18th century, the Italian peninsula was fractured into parts controlled by different nations. A century later, the notion of a united Italy had evolved into a battle for independence, pitting Italy’s revolutionaries against the might of Austria and the Papal States. Although soldiers and statesmen played a key role in what unfolded, Giuseppe Verdi’s music provided the soundtrack to the desire for independence. Through his many works, Verdi reflected, and even shaped, the struggle for Italian unification known as Il Risorgimento: the Resurgence.

Italy’s fragmentation had deep roots in its past. The collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the Middle Ages broke Italy into city-states that took center stage during the European Renaissance. In the early modern period, central Italy was dominated by the papacy, while the rest of the Italian peninsula fell under the control of foreign powers, such as Spain and France.

After the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Austria strengthened its grip on northern Italy. At the same time a surge in anti-imperialism and nationalism began to grip Europe. Chafing under the yoke of Austrian control, many Italians yearned for a nation of their own and fought for it from the 1840s until achieving full independence in 1870.

Timeline: Masterpiece Upon Masterpiece

1838-1840

Despite professional successes, Giuseppe Verdi endures personal tragedies, losing his wife and two children over three years.

1841

To overcome his grief, Verdi throws himself into a new opera, Nabucco, which will debut in 1842 and begin a comeback for the composer.

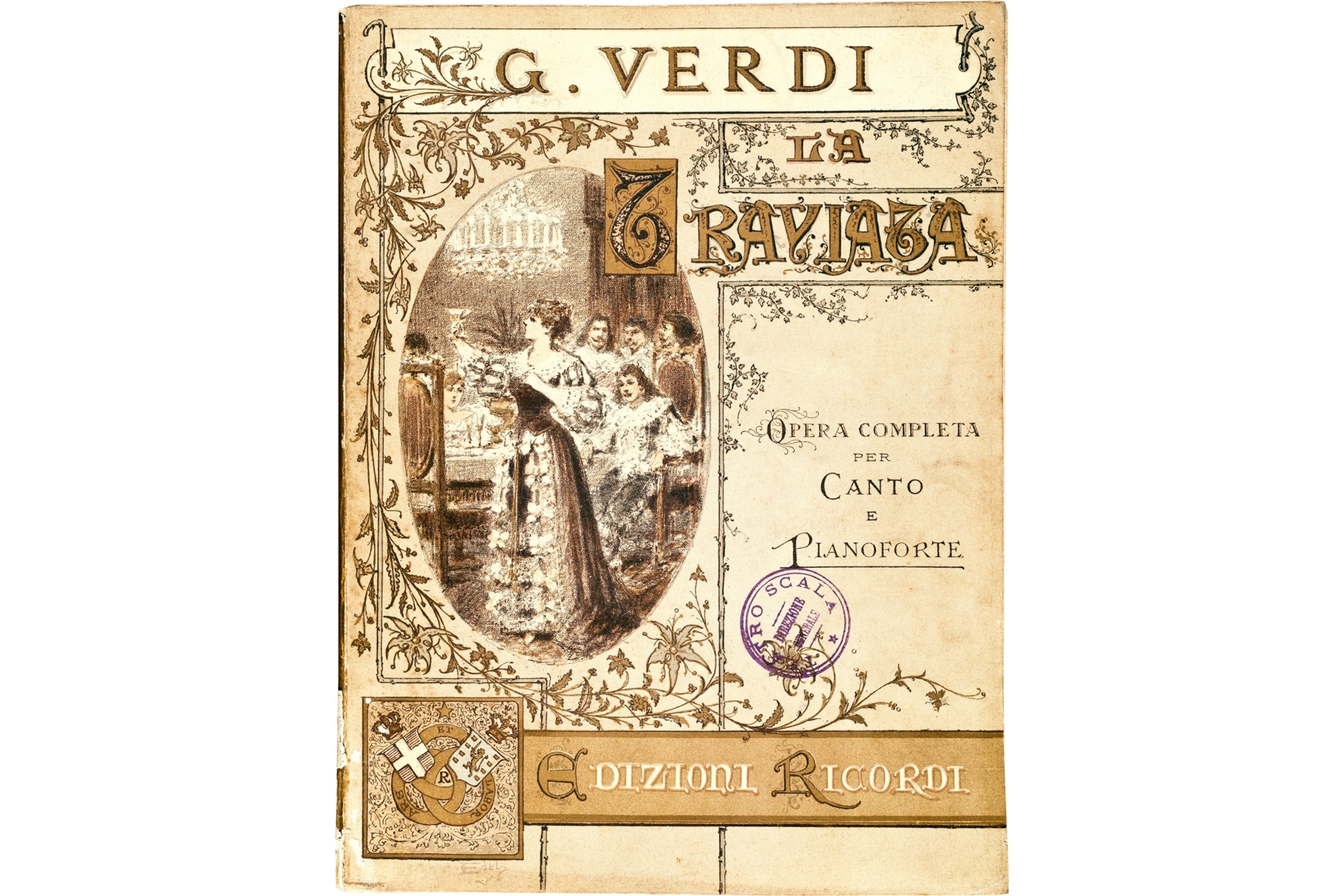

1851-1853

Years of brilliance: Verdi debuts Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, and La Traviata. All three rank among his best loved and lasting works.

1871

Commissioned for the opening of the royal opera house, Aida debuts in Egypt and will become one of the world’s most popular operas.

1901

Verdi dies in Milan. At his funeral, the great Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini leads an orchestra through Verdi’s greatest pieces.

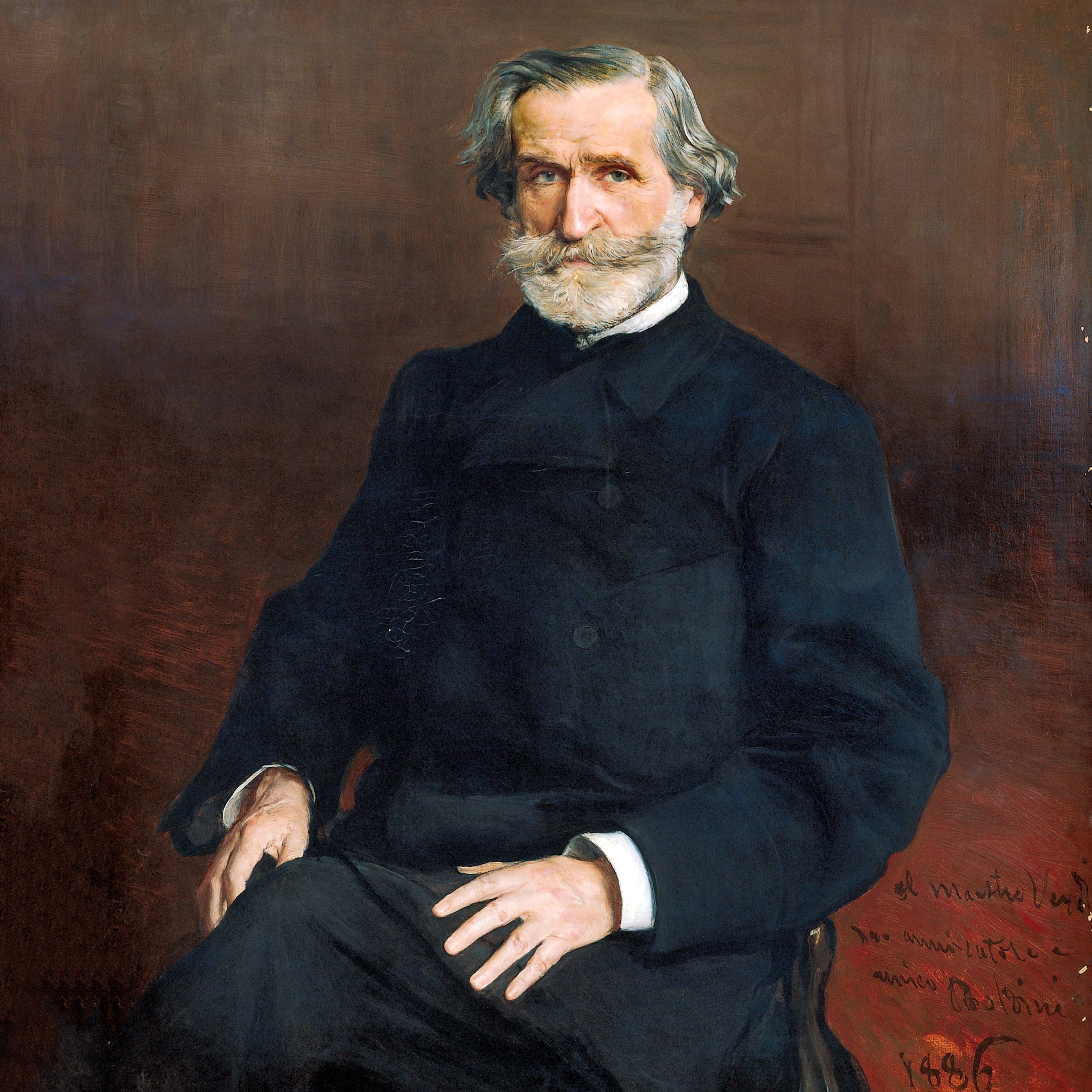

Talent and Tragedy

Verdi’s life spanned two ages and two Italys. He was born in 1813 in the small duchy of Parma, at the time under Napoleonic rule, and died in 1901 in Milan, then the commercial capital of the newly independent Italian nation.

The son of an innkeeper, Verdi possessed an immense musical talent that could not be overlooked; by age 12 he served as the organist for his village’s church. He continued his education in Busseto and then Milan, the intellectual and operatic center of Italy. At the age of 26, Verdi’s first opera, Oberto, premiered at Milan’s La Scala in November 1839.

Despite early triumphs, Verdi’s life was overshadowed with tragedy as well. His two children, Virginia and Icilio, died in 1838 and 1839, respectively, followed by his wife, Margherita, in 1840. His personal sorrow was compounded by a sense of professional failure when his second opera, Un giorno di regno, which premiered in Milan in 1840, was a spectacular commercial flop.

Verdi slipped into deep depression until a winter’s day in 1841 when a colleague insisted he consider creating an opera based on a work by the poet Temistocle Solera. Accounts say that when Verdi carelessly tossed the manuscript on his desk, a fateful moment occurred. Years later, Verdi recalled “how the book opened in falling, and without knowing how, I gazed at the page that lay before me and read this line: Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate [“Go thought, on golden wings”] and I could not get it out of my head.”

Chorus of Approval

Twenty of his 30 operatic works are still regularly performed in the great opera houses across the world, proving Verdi is as adored now as he was by the Italians who marked his death in 1901 with a national outburst of grief. Although historians argue that the link between his music and nationalism may have formed more gradually than is often claimed, his work resonated deeply with the people. In 1855, an Italian writer noted: “With what marvelous avidity the populace of our Italian cities was seized by these broad and clear melodies singing as they went ... confronting the grave reality of the present with aspirations for the future.”

Protest Songs

Solera’s manuscript recounted the hardship the Jewish people suffered under the despotic rule of the Babylonian tyrant Nebuchadrezzar, Nabucco in Italian, who conquered Jerusalem and exiled the Hebrews to Babylon. Many of his Italian compatriots would understand the symbolism: the Jews were the Italians, and Nebuchadrezzar, the Austrian Empire’s tyranny. As a fervent patriot and staunch supporter of the liberal ideals sweeping Europe, Verdi thrust his sorrow aside and poured his artistic potential into breaking the oppressor’s yoke through music.

One year later, on March 9, 1842, Nabucco premiered at the La Scala theater in Milan. It was a stunning success. In its first year it was performed an astonishing 64 times. The most famous piece, the “Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves,” came in the third act and began with the lines Verdi saw in the book: Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate. The Hebrews are lamenting the loss of their homeland, a sentiment to which many Italians in the audience could relate. Over the following decades, the chorus became something of an unofficial anthem for the revolution.

Although Italian nationalism was led to victory by soldiers like Giuseppe Garibaldi, Verdi’s music provided a huge emotional boost to Il Risorgimento. After Nabucco, Verdi was aware of the unusual responsibility he faced as an artist. Fame came at a price, however: Verdi was soon attracting the attention of the Austrian authorities in Italy, and his criticism of ecclesiastical power was likely to offend the powerful Catholic Church.

Despite enjoying the protection of the Countess Clara Maffei, a leading patron of the arts in Milan, trouble loomed for the composer. Shortly after his next opera, I Lombardi, premiered in 1843, Verdi had his first clash with censorship. The archbishop of Milan reported rumors that the work attacked Catholic rites, and threatened to write to Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I to make a formal complaint. The next day, the imperial police told the company that I Lombardi could not be performed unless passages were changed. The composer refused to edit a single note and said it would be performed as it was or not at all. The chief of police responded, saying: “I will not be the man to clip the wings of so promising a genius.”

Emboldened, Verdi embarked on a series of great operas suffused with nationalism. Attila (1846) tells of the hated Huns’ arrival in Italy in the fifth century. The final act of his Macbeth (1847) opens with its stirring “Patria oppressa” chorus: “Oppressed land of ours! ... now you have become a tomb for your sons. ”Even as he enjoyed such success, however, Verdi’s self-confidence was not boundless. In 1853, he still feared his latest opera, La Traviata, could be a flop.

Viva V.E.R.D.I.

During the struggle against Austrian rule, Italian patriots painted “Viva Verdi” on walls. The graffiti was both an expression of admiration for the musician, whose surname also conveniently formed the acronym: Vittorio Emanuele Re d’Italia—Victor Emmanual, King of Italy.

Rome Comes Together

In later life, Verdi became heavily involved in politics. In 1859, he was elected to a provincial council that paid an official visit to Piedmont, where he met the new “Father of the Homeland,” King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia. The following year, the whole of the southern peninsula, known as the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, became part of Italy. Venice would follow in 1866, but Rome remained part of the Papal States.

Verdi accepted a position as representative in the first Italian parliament, but in 1865, he retired in order to focus on music. His next great work, Don Carlos (1867), reflected the desire to bring Rome into the unified nation. The opera includes a magnificent scene with two bass roles: a villain, Philip II of Spain, and an even worse villain, the Grand Inquisitor. The anti-Spanish theme was symbolic, as Spain had long ceased to exert influence over Italy—Verdi’s real target was the church, whose power and greed, Verdi believed, was holding back the final goal of Italian nationalism.

With Don Carlos, the composer was readying his public for the conquest of Rome, and the fall of the outdated papal states. Three years after Don Carlos premiered, on September 20, 1870, Italian troops entered Rome, and unification was finally complete.

The new Italian state recognized Verdi’s colossal artistic and political contributions, appointing him a life senator. However, a radical to the end, Verdi was disappointed by the nation’s social inequality and preferred to remain in Busseto, in a villa that is now a museum. The composer’s unused train tickets to attend the Senate in Rome can still be seen there. Soon after his death, at the dawn of the 20th century, his neighbors gathered outside his home to sing the “Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves,” the great gift he had bequeathed Italy.

Keeping the Score

Like any good artist, Verdi knew the importance of suspense and surprise, so much so that he even kept his performers in the dark. During the rehearsals for Rigoletto, the tenor realized that his part was missing from the score; he kept reminding the composer, who always replied, airily: “Oh, I will give it to you in time.” In fact, the tenor was only given the score the night before the premiere and was told to practice in secret. Why? Because the piece would be his most famous aria: “La donna è mobile” (“The Woman is Fickle”) which Verdi had sensed—rightly—would become a smash hit.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- This tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyraamidThis tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyraamid

- Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursDina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?