Igor Stravinsky and the Concert That Wasn't

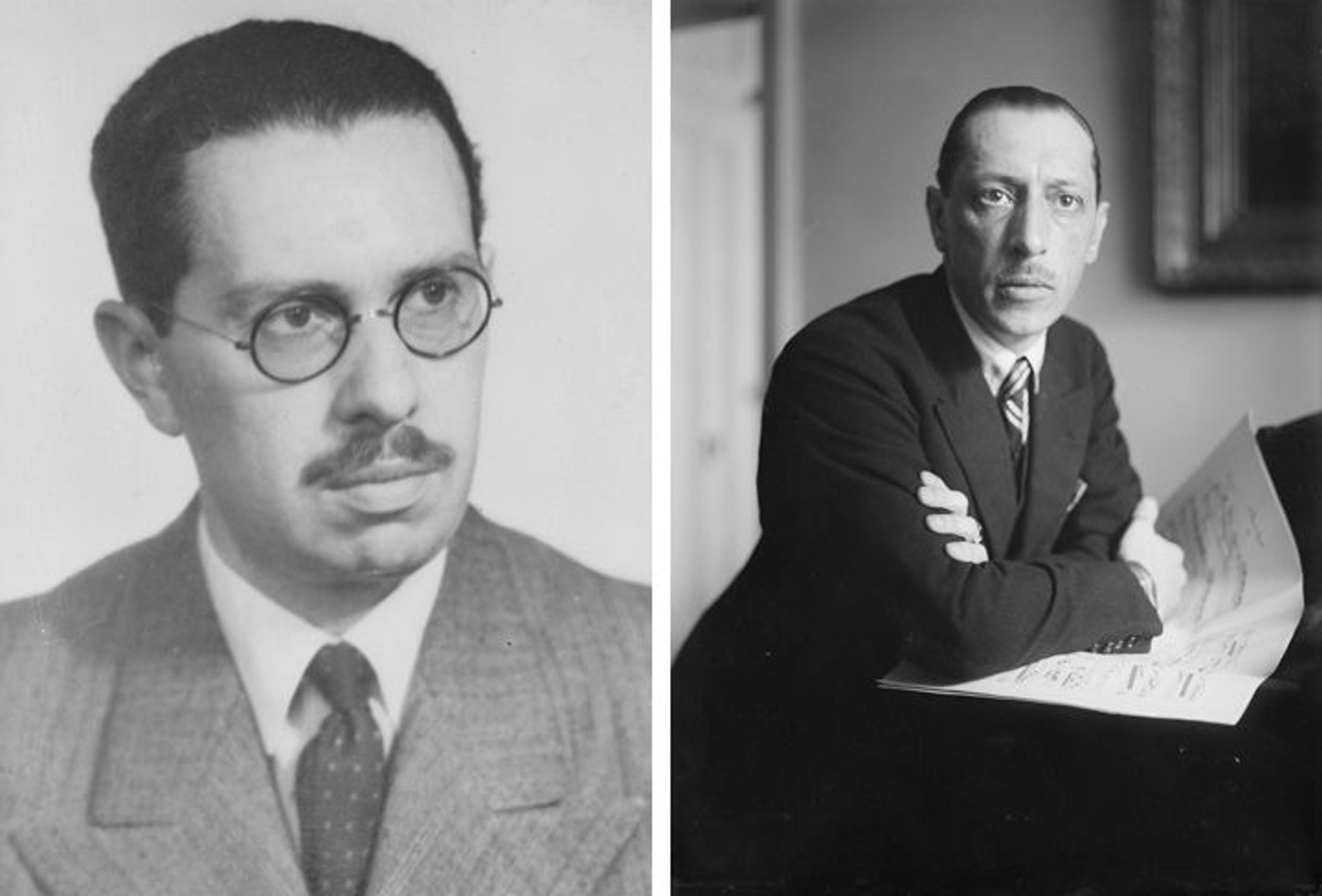

Left: Emanuel Winternitz, former curator in the Department of Musical Instruments, 1941. Right: Igor Stravinsky, undated photo. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

«It was Valentine's Day 1946. As he recalled in his memoirs written nearly 40 years later, a bemused Met curator, summoned to a suite in the Waldorf-Astoria, watched an "opera buffa" scene as the suite's occupant "chased seven cousins out the left door while seven came back in the right door. Finally there was peace and he told me that he approved the idea for a concert." The Met curator was Emanuel Winternitz, and the composer of the scene was Igor Stravinsky, who had asked Winternitz to come over so that they could discuss a project near and dear to both men's hearts: the first Western hemisphere performance of Stravinsky's 1918 composition L'Histoire du Soldat. The performance was to take place at The Met as part of the extraordinary concert series that Winternitz had inaugurated in 1942 and continued until 1961.»

Winternitz's musical programming placed the Department of Musical Instruments at the forefront of New York's classical-music scene in the 1940s and '50s. His contacts among the world's great conductors, composers, and performing artists—particularly those who, like himself, were from war-torn Europe—enabled him to attract talent ranging from the Budapest String Quartet in a rare Western performance in 1946, to Sir Thomas Beecham and Dame Myra Hess. As a result, the department was formally known in the Museum as the Department of Musical Activities.

Winternitz generally focused his concert programming on what we now call "early" music and, in particular, on little-known pieces. However, Winternitz himself was a student of 20th-century classical music. As a young man in Vienna, he had known many of the composers and players who, like Stravinsky, were pushing the boundaries of musical forms. In the summer of 1945, he envisioned a radical departure from his programming to date: asking Stravinsky to mount L'Histoire du Soldat at The Met. The work was Stravinsky's version of the Faust legend, and was designed to be staged with a narrator, several dancers, and seven musicians. After its premiere by Serge Diaghilev's Ballet Russes in 1924 in Paris, only a handful of other performances occurred from 1925 to 1927, in Germany and England. The work had not been performed since 1927 and had yet to be recorded, meaning that few people in 1940s America would have heard it.

By September 27, 1945, Winternitz's plans for staging L'Histoire covered two pages of detailed notes on everything from costumes to the number of spotlights needed and the anticipated cost of hiring the necessary performers. The next day, Winternitz obtained Stravinsky's California address from a friend and wrote asking whether the composer would be interested in a Met performance of the work, which Winternitz noted "has always been a great favorite of mine." Winternitz's letter continued: "We have never tackled modern music before in our series . . . but if you will lend us your cooperation, we shall be glad to pleasantly surprise our audience by presenting them with great music of the present."

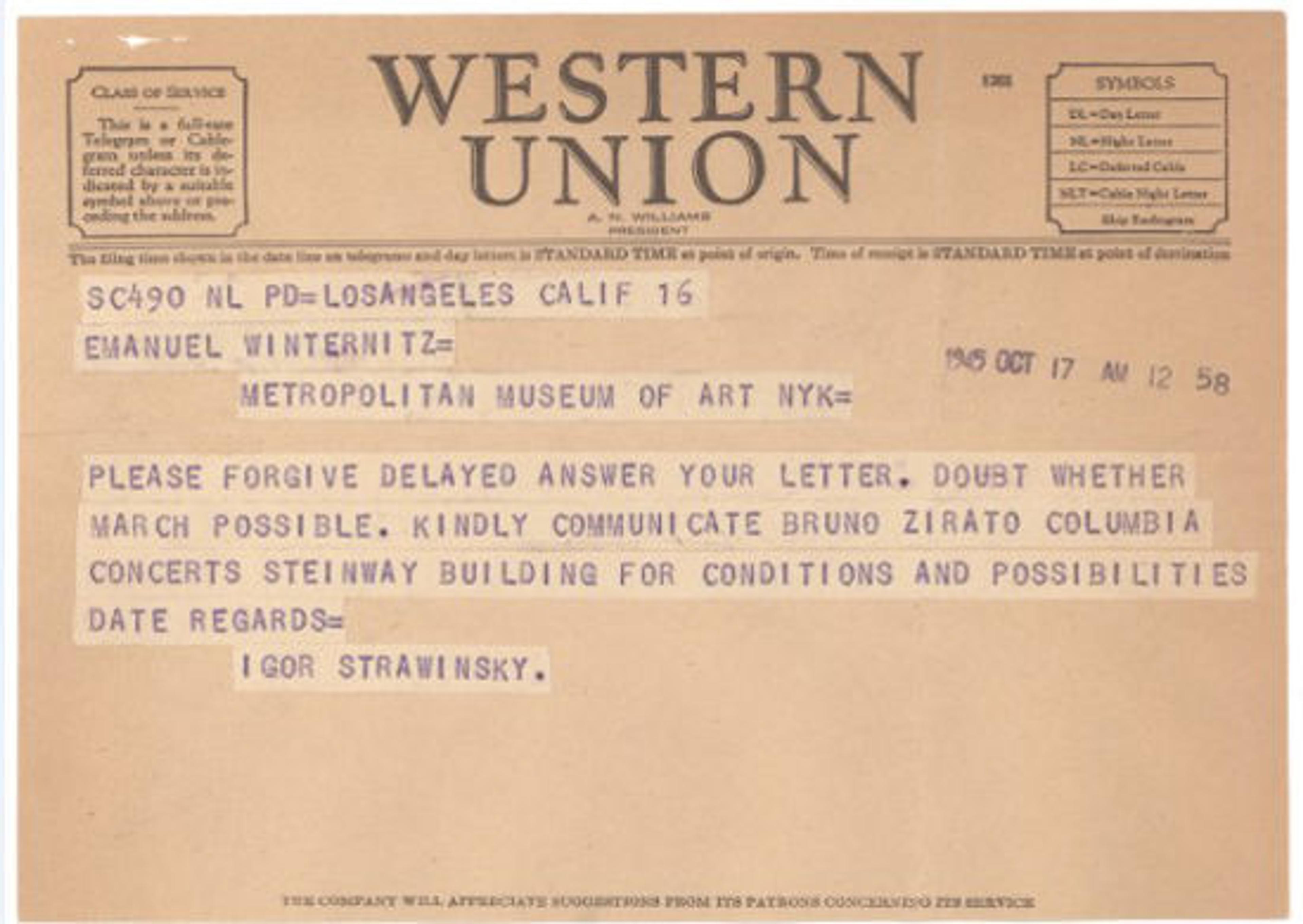

Stravinsky responded by telegram to confirm his interest. Throughout the fall of 1945, the two communicated about the project, and by December 11 Stravinsky's agent in New York, Bruno Zirpato, was pressing Winterntiz: "Mr. Stravinsky is very anxious to do L'Histoire du Soldat at the Museum." Stravinsky proposed specific rehearsal and concert dates, but Winternitz was forced to let Zirpato know that the Museum schedule for the present year was "completely filled," and urged that Stravinsky get in touch with him when the latter was in New York to "make plans for next year."

Memo from Stravinsky to Winternitz, October 17, 1945

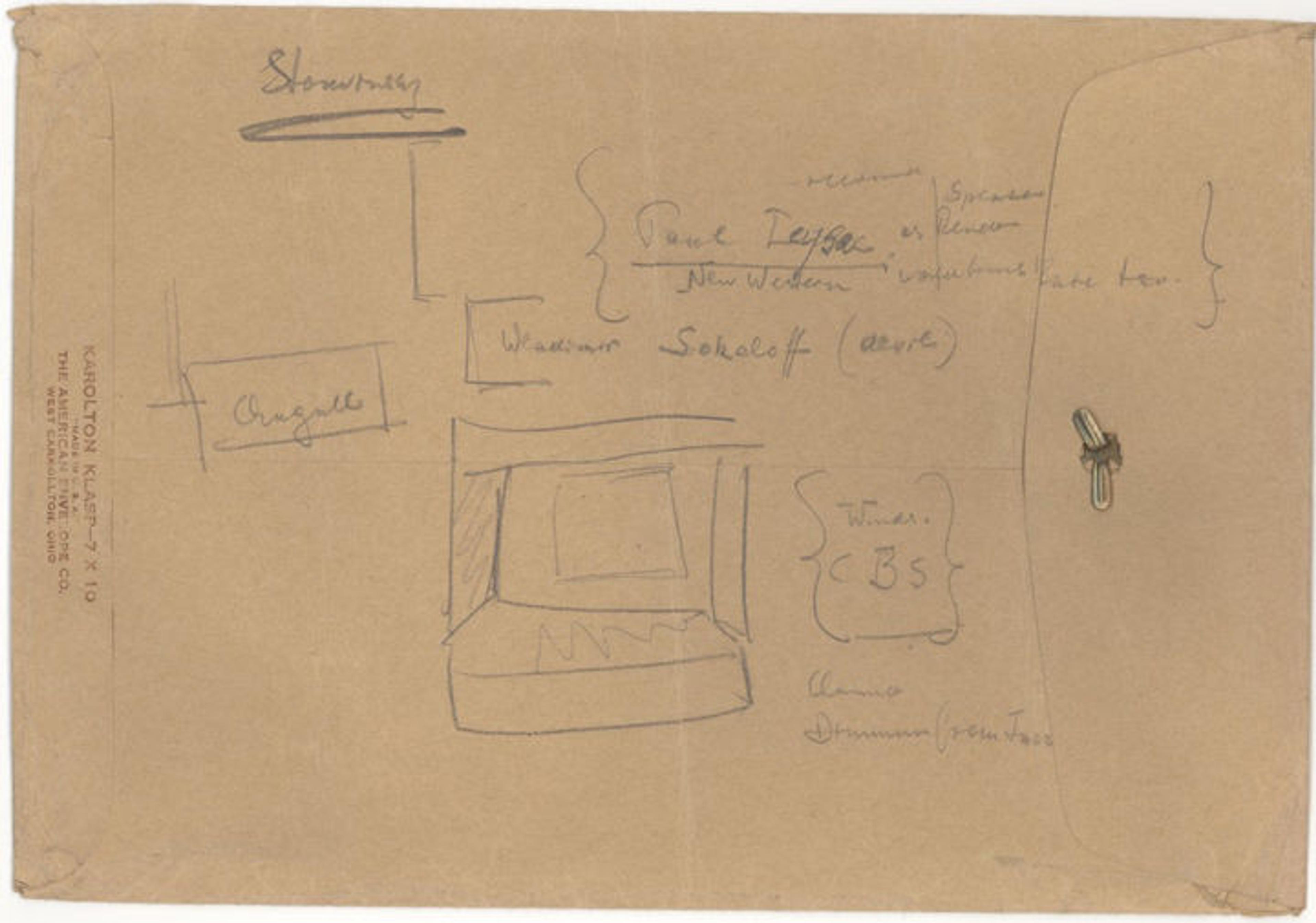

A few weeks later, on February 14, 1946, when Stravinsky was in New York for concerts with the New York Philharmonic, he called Winternitz to meet him at the Waldorf. Winternitz took notes of that meeting quite literally on the back of an envelope, and typed a file memo just after the meeting saying that Stravinsky was "very anxious to do it."

As Winternitz's memoir described the conversation, Stravinsky wholeheartedly joined in Winternitz's desire to do a fully staged, costumed performance. Stravinsky had "a friend in Chicago" who would do the costumes "cheaply of course," and "a friend who is a gifted painter in Los Angeles" to do the sets "quite inexpensively." The notes on the back of the envelope are clearer: Marc Chagall was to do the sets, the Russian actor Vladmir Sokoloff (1889–1962) was to play the Devil, and Paul Leyssac was to translate the text into English. Winternitz's own contribution was the idea of dressing the musicians as insects.

Winternitz's notes, written on the back of an envelope during his meeting with Stravinsky in February 1946

Sadly the project never came to fruition. Three months later, on May 15, 1946, Bruno Zirato again asked Winternitz whether he wanted the work performed "next season." Winternitz penciled a note to say that he had telephoned a response in June to say the Museum's budget would not be ready until late fall. Two problems seem to have sunk it: scheduling and budget. Although Stravinsky was more than willing to do two performances at The Met in 1945, and indeed proposed specific dates, in 1946 he was only able to commit to one concert date, and Winternitz programmed all of his concerts for two performances in order to meet demand. In addition, at least in Winternitz's recollection, Stravinsky's interest in the project diminished after Winternitz described the meagre funds The Met had available to pay fees.

Stravinsky was right to have wanted The Met to stage his work. There was no United States performance of any kind of L'Histoire until 1978, when George Balanchine and the New York City Ballet mounted a dance version. Following the failure of the Stravinsky project, it was many years before contemporary classical music was performed at the Museum. Winternitz's success with early music, and his focus on using the instruments in The Met collection, all of which dated to the 19th century or earlier, meant that he did not again attempt to program great works of the 20th century.

Related Links

Of Note: "Emanuel Winternitz and the Museum's Member Concerts" (July 27, 2015)

A Harmonious Ensemble: Musical Instruments at the Metropolitan Museum, 1884–2014, a comprehensive account of the history of the Department of Musical Instruments written by Rebecca Lindsey.

Rebecca Lindsey

Rebecca Lindsey is a member of the Visiting Committee of the Departments of Musical Instruments and Islamic Art.