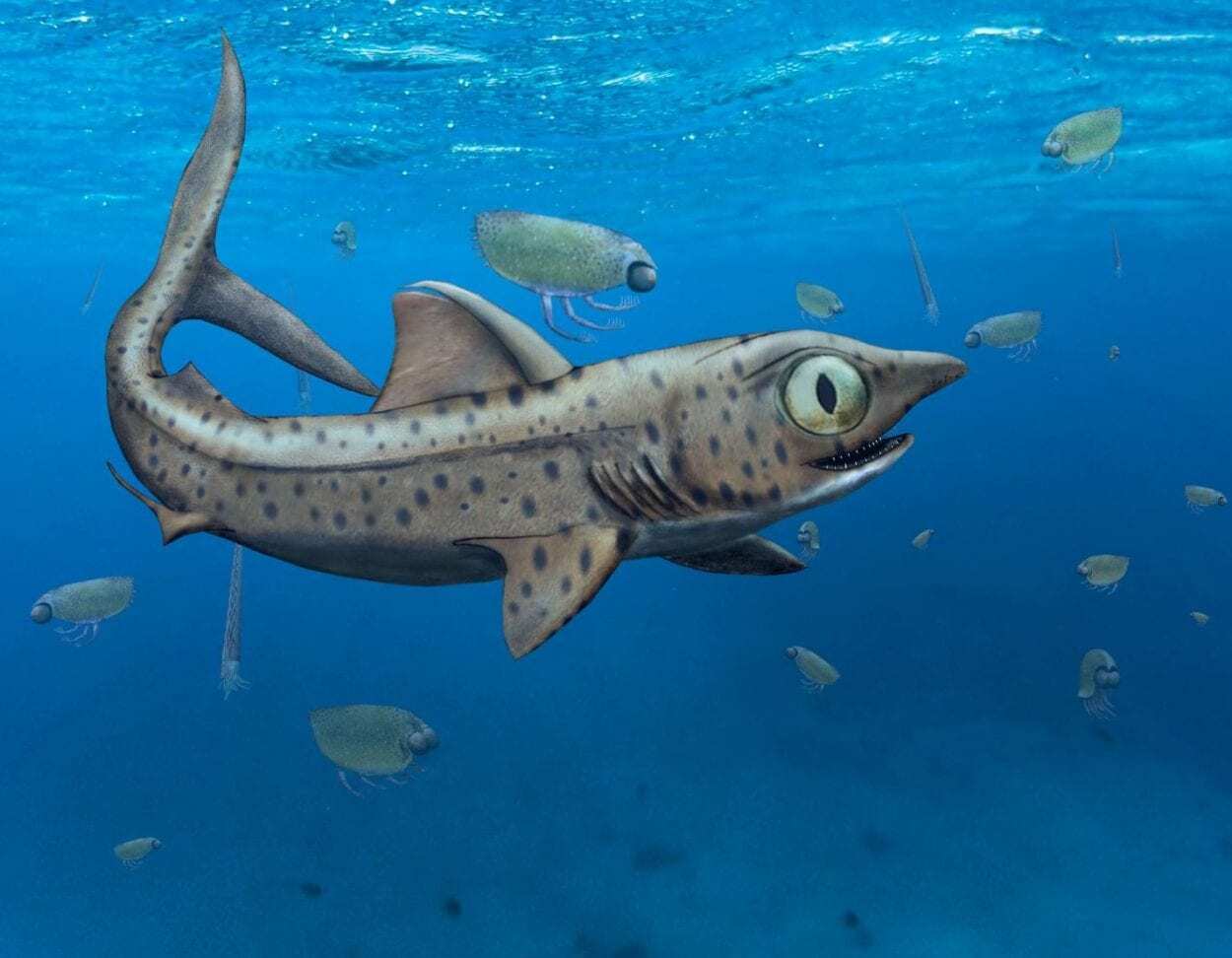

Some, if not all, early sharks that lived 300 to 400 million years ago not only dropped their lower jaws downward but rotated them outwards when opening their mouths.

This enabled them to make the best of their largest, sharpest and inward-facing teeth when catching prey, paleontologists at the Universities of Zurich and Chicago have now shown using CT scanning and 3D printing.

Many modern sharks have row upon row of formidable sharp teeth that constantly regrow and can easily be seen if their mouths are just slightly opened. But this was not always the case.

The teeth in the ancestors of today’s cartilaginous fish (chondrichthyan), which include sharks, rays and chimaeras, were replaced more slowly. With mouths closed, the older, smaller and worn out teeth of sharks stood upright on the jaw, while the younger and larger teeth pointed towards the tongue and were thus invisible when the mouth was closed.

Jaw reconstruction thanks to computed tomography

Paleontologists at the University of Zurich, the University of Chicago and the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden (Netherlands) have now examined the structure and function of this peculiar jaw construction based on a 370-million-year-old chondrichthyan from Morocco. Using computed tomography scans, the researchers were able not only to reconstruct the jaw, but also print it out as a 3D model. This enabled them to simulate and test the jaw’s mechanics.

What they discovered in the process was that unlike in humans, the two sides of the lower jaw were not fused in the middle. This enabled the animals to not only drop the jaw halves downward but at the same automatically rotate both outwards.

“Through this rotation, the younger, larger and sharper teeth, which usually pointed toward the inside of the mouth, were brought into an upright position. This made it easier for animals to impale their prey,” explains first author Linda Frey. “Through an inward rotation, the teeth then pushed the prey deeper into the buccal space when the jaws closed.”

Jaw joint widespread in the Paleozoic era

This mechanism not only made sure the larger, inward-facing teeth were used, but also enabled the animals to engage in what is known as suction-feeding. “In combination with the outward movement, the opening of the jaws causes sea water to rush into the oral cavity, while closing them results in a mechanical pull that entraps and immobilizes the prey.”

Since cartilaginous skeletons are barely mineralized and generally not that well preserved as fossils, this jaw construction has evaded researchers for a long time. “The excellently preserved fossil we’ve examined is a unique specimen,” says UZH paleontologist and last author Christian Klug.

He and his team believe that the described type of jaw joint played an important role in the Paleozoic era. With increasingly frequent tooth replacement, however, it became obsolete over time and was replaced by the often peculiar and more complex jaws of modern-day sharks and rays.

Header Image Credit : Christian Klug, UZH