A Look Back At The Life Of Emilie Schindler, The Wife Of Oskar Schindler

How often does one have a chance to save 1,200 people? Unfortunately, during World War II, too many Germans passed on the opportunity to save lives. But Emilie and Oskar Schindler — whose story became popularized by the 1993 film "Schindler's List" — found themselves well-positioned to make a small dent in Hitler's genocide machine and seized the moment.

That's not where Emilie's story begins, however. While not as much is known about her as about her famous husband, she was reportedly the spartan moral center to his gallivanting sybarite. For Emilie, it all started in the peaceful Moravian town of Alt Moletein, where she was raised by a loving nuclear family. As David Crowe explains in "Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account," Emilie grew up taking after her mother — a "patient and lovely" woman — and learning to adore horses from her father.

Later, Emilie would recount the time during her childhood when she met an old mystic woman who said she could see the young girl's future. The woman told Emilie that she would one day meet a man who would whisk her away from Alt Moletein, and Emilie would love this man above everything else — "although you will not be happy at his side." She went on to warn Emilie that she would endure "pain and suffering," and that unspeakable things would happen down the road. At the time, Emilie fled in fear, but she never forgot the woman's predictions — many of which would turn out to be true.

Meeting her future husband

Emilie Pelzl met Oskar Schindler in the autumn of 1927 when she had just turned 20. According to "Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account," Oskar and his father showed up at Emilie's home attempting to persuade her father to buy a piece of electrical equipment. By Emilie's telling, as recounted in "Oskar Schindler," Oskar was not very engaged in his father's salesmanship, but he was enthralled with Emilie, staring at her with "deep blue eyes."

It only required a few return visits to the Pelzl family farm before Oskar was able to sweep Emilie off her feet. The relationship deepened, and then their respective families also met. Oscar went on to ask Emilie's parents for Emilie's hand in marriage. Emilie later told a German newspaper that her father had warned her about Oskar: He had a "false charm," the by-now ailing old man told his daughter. But her home life was beginning to feel claustrophobic and Emilie was completely taken with Oskar. According to Jewish Virtual Library, the couple wed on March 6, 1928, at an inn near Oskar's hometown.

Skipping the honeymoon period with Oskar

Oskar Schindler received a dowry worth about 100,000 Czech crowns from Emilie's father when he married her, per the Jewish Virtual Library. He promptly spent it on a fast car, according to "Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account." When Emilie protested, Oskar reportedly shrugged it off, telling her she was "too austere, a real ascetic."

After they married, the duo took up residence in Oskar's parents' house. It was not a pleasant change for Emilie. Oskar's father was a mean-spirited alcoholic, and his mother, while a sharp contrast to her husband, spent most of her time stuck in bed, for reasons that are unclear. Emilie struggled to carry out her household chores in the Schindler house while also tending to her family back in Alt Moletein.

Before long, the Moravian Electric Company where Oskar had been working went bankrupt. He was then unemployed, and his spending habits (specifically, on alcohol) became a source of conflict between him and Emilie. Police arrested him multiple times during this period — for "public drunkenness, disorderly conduct, and assault" — and eventually sent him to jail for a short time.

Laying the groundwork for saving lives

In 1931, Oskar Schindler left Emilie Schindler behind and sought work in Berlin. Around this time, he had an affair and fathered two children outside of their marriage. Emilie knew of the affair and vacillated between anger and acceptance after Oskar's charming apologies, per "Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account." As Emilie wrote in her 1997 memoir, "Where Light and Shadow Meet" (via Jewish Virtual Library), the couple would quarrel and reconcile repeatedly.

"In spite of his flaws, Oscar had a big heart and was always ready to help whoever was in need," Emilie wrote. "He was affable, kind, extremely generous and charitable, but at the same time, not mature at all. He constantly lied and deceived me, and later returned feeling sorry, like a boy caught in mischief, asking to be forgiven one more time — and then we would start all over again."

Around 1937, Oskar joined the Abwehr, the German counterintelligence forces. It was here that he forged the contacts he would later need to save over 1,000 Jews. (Among those contacts was Franz von Korab, an Abwehr commander who was secretly half-Jewish and made it possible for Oskar to lease a factory in Krakow.) Emilie and Oskar were not living together during his initial years as an Abwehr agent, and Oskar was briefly imprisoned by the Czechs, but when he was released, he got a promotion and some serious street cred among Hitler's forces.

Living in Krakow as Nazis

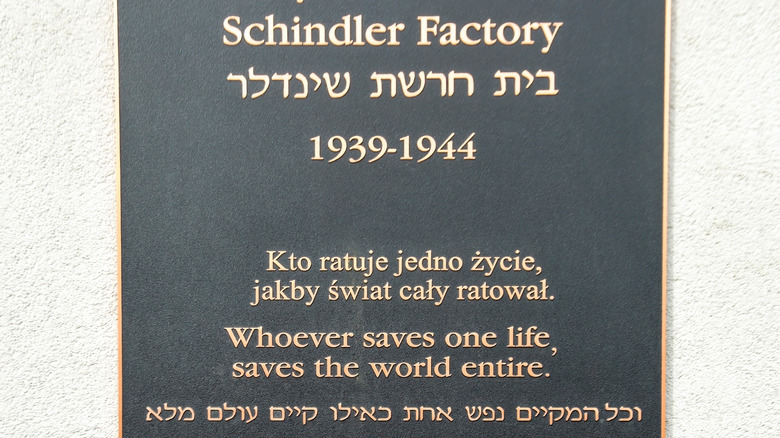

The couple was together again by January 1939, when Emilie Schindler began serving as Oskar Schindler's assistant. They moved to Krakow that year, taking over the formerly Jewish-owned manufacturing facility after the Nazis seized Poland, and would stay there through 1944. Emilie reportedly said Oskar was more faithful to that city than he was to any woman, including her, per "Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account."

While the Third Reich viewed Poland as a testing ground for its war on Jews and fellow minority groups — Afro-Germans, Poles, Jehovah's Witnesses, gay people, the mentally ill, and the disabled, among others, per the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia — there were some in Abwehr who quietly opposed the SS and its methods during the Holocaust. Oskar Schindler came to know who they were and later used them to help save Jews and himself after he was arrested thrice during the war.

As the wanton cruelty of Hitler's regime became unavoidably clear, Emilie and Oskar decided to save the workers from the Jewish ghetto that Oskar had been exploiting as cheap labor, according to the Jewish Virtual Library. Like millions of other Jews, those workers were soon at risk of being carted off to Nazi death camps, and during this time, Emilie encouraged the big heart of Oskar that had saved their marriage to also save his workers from his Nazi colleagues.

Classifying their Jewish workers as 'essential'

To keep their workers out of Nazi concentration camps, Emilie and Oskar Schindler dubbed them "essential workers" and protected them from beatings, starvation, and torture — although many of the workers still suffered freezing conditions, lice infestations, typhus, and dysentery, per the Jewish Virtual Library. Suddenly, Oskar's vices — his garrulous, restless nature, his duplicity, his craving for adrenaline and risk — were put to good use as he charmed his way past SS roadblocks.

Emilie manned the secret hospital they set up on the factory grounds and cared for the sick there. She traded her jewelry on the black market to secure food, clothing, and medicine for the trapped workers, according to the Arizona Jewish Historical Society. And she and Oskar bribed the Gestapo to leave their workers alone. Despite that, not all of their workers survived these years, and the Schindlers ensured that those who didn't received a Jewish burial in a secret graveyard set up by Emilie and Oscar. By the end of the war, they had spent somewhere in the neighborhood of 4 million German marks trying to save the workers in their factory.

Daring to ask a local aristocrat for grain

As Oskar Schindler wined and dined Nazi officials in Krakow, Emilie Schindler fed and cared for the Jews in their factory. According to the Arizona Jewish Historical Society, one Holocaust survivor, Maurice Markheim, later described a time when Emilie secured a truckload of bread from the black market. Markheim got to help unload it. "A loaf of bread at that point was gold," Markheim explained. "She was talking to the SS and because of the way she turned around and talked, I could slip a loaf under my shirt. I saw she did this on purpose."

The black market did not always meet the Schindlers' needs, however. On one occasion, desperate for food, Emilie took the chance of reaching out to a local aristocrat's wife, Frau von Daubek, and begging for grain from her mill. Emilie reportedly felt she had no choice. She did not try to trick von Daubek but simply confessed that she needed food for her Jewish workers. Emilie's gamble paid off. Von Daubek offered to donate some grain to help the Schindlers.

Other survivors have recounted (via the Jewish Virtual Library) how Emilie personally replaced a young Jewish boy's eyeglasses after they were broken, and how she expended tremendous energy during this time trying to help the Jews in their care. Feiwel (later Franciso) Wichter, one of the lucky ones to make Schindler's list, later said that Emilie was "like a mother" to the people stuck there.

Braving arrest by the Gestapo

During these years, Emilie Schindler lived in fear not only for her own life and for the lives of their workers, but also for Oskar Schindler's. Her husband was arrested three times during their stay in Krakow as he gradually shed many of his selfish ways and made saving the Jews in his factory a personal project. Each time, the SS charged him with "favoring Jews," but his Abwehr connections and Nazi drinking buddies got him released into Emilie's anxious arms, according to Yad Vashem.

When the Krakow ghetto Jews were sent to a slave labor camp in Plaszow in 1943, Emilie and Oskar got the Nazis to let them set up separate camps for their Jewish workers, where Emilie fed them extra food secured through the black market. The Schindlers then got their compound labeled off-limits for the local SS guards.

Outside the Schindlers' camp, the roughly 20,000 remaining Jews sent to Plaszow would later be shipped off to Auschwitz. Those who died at Plaszow had their corpses set ablaze by the Nazis as the Russians advanced, an effort to cover up what had happened there, per Britannica.

Drawing up the list

In 1944, with the Russians bearing down on Poland, the Nazis began sending Plaszow's occupants to concentration camps. It was at this point that Emilie and Oskar Schindler began compiling a list of people to save, per the Arizona Jewish Historical Society.

They moved them to what was supposed to be a bullet factory in Brunnlitz, in Oskar's home province, although the factory never churned out one militarily usable bullet over the course of the Schindlers' time there. On their way to Brunnlitz, 800 of the men on Schindler's list and 300 of the women were waylaid and shipped to the Gross-Rosen and Auschwitz concentration camps. According to Yad Vashem, Emilie and Oskar found out about it and negotiated furiously to get those people back. First, the men were released to the Schindlers, and then, after Oskar sent his personal secretary to Auschwitz to barter with the Nazis there, the 300 women were sent on to Brunnlitz without being gassed — the only known instance in which a large group of Jews escaped the camp alive.

Blocking Nazis from carting starving Jews to Auschwitz

In 1945, as the war was drawing to a close, Emilie Schindler faced a harrowing situation, one which would become possibly her finest hour during the Holocaust. Through circumstances that are unclear, several railway cars bearing up to 250 half-starved Jews arrived at the gates of Brunnlitz one night. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, Oskar Schindler was in Krakow at the time.

The SS officer in charge of the area wanted to send the cars to Auschwitz, and according to The New York Times, Emilie stopped him. Having reached Oskar and secured his support, she persuaded the Nazis that the Jews were necessary to the Schindlers' factory and the war production effort it was supposedly supporting. In her memoir, "Where Light and Shadow Meet," (via JVL) Emilie recounted the horrifying sight that greeted her upon prying the cars open.

"We found the railroad car bolts frozen solid," Emilie wrote. "The spectacle I saw was a nightmare almost beyond imagination. It was impossible to distinguish the men from the women: they were all so emaciated — weighing under 70 pounds most of them, they looked like skeletons. Their eyes were shining like glowing coals in the dark."

Fleeing the Russians

In May of 1945, Emilie and Oskar Schindler fled their factory ahead of the Russian advance. On the night before they left, they assembled their 1,000-plus workers in the factory and said heartfelt goodbyes to the people they had worked so hard to save, according to the Jewish Virtual Library.

Oskar somehow managed to get himself and Emilie back into Germany, but they had used up essentially all of their money protecting their factory workers and themselves, per Yad Vashem. According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia, Emilie and Oskar tried to live in Regensburg, Germany for a while. But the Schindlers were stripped of their nationality immediately following the war, and Oskar and Emilie faced threats to their lives from devoted ex-Nazis furious about their deceptions.

They could not emigrate to the U.S. because Oskar had been a member of the Nazi party. As the USHMM Encyclopedia points out, the U.S. granted asylum to somewhere between 180,000 and 225,000 refugees fleeing the Nazis from 1933 to 1945. But those numbers fell short of quotas, and the Nazis murdered 6 million Jews (along with many other people, including other minorities, dissidents, and Allied soldiers) over the course of the war.

Moving to Argentina

In 1949, Emilie and Oskar Schindler made it to Argentina, impoverished. According to The Guardian, they settled in the Buenos Aires area, and Emilie took over the mink farm they had bought to support themselves, while Oskar took to heavy drinking. In 1958, Oskar's big heart failed him and he followed in the footsteps of his father, who left Oskar's mother on her deathbed, per "Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account." Oskar ditched Emilie and fled back to Germany, according to The New York Times. He left in his wake a heavy debt load, per The Guardian.

Though the Schindlers never divorced, they never spoke again. Emilie refused to answer Oskar's letters from Germany, embittered over being left financially destitute. When her husband died in 1974, Emilie declined to attend his funeral. Oskar was 66 years old when he passed, and was buried in Israel's Catholic cemetery on Mount Zion, according to History.

Returning to Germany

For years, Emilie Schindler subsisted on a pension from a Jewish group, B'nai B'rith, which the German government later added to. She did not socialize much in Buenos Aires and was staying in a tiny, dilapidated house during those years, per The Guardian. In 2000, Emilie finally made it back to Germany herself — a longtime wish of hers. For a while, she lived in a Bavarian seniors' home. But not long after she arrived at the seniors' home, Emilie suffered a stroke and had to move to a Berlin-area clinic. She remained there for two months before she died.

Emilie reportedly insisted on wearing her wedding ring until the day she died. The old mystic's prediction had come true: Emilie had sacrificed everything for Oskar — including, up until her last days, her country — but her husband had not made her happy in the end. Nonetheless, toward the end of her life, Emilie was quoted as saying, "If I could choose again, I would pick Oskar."