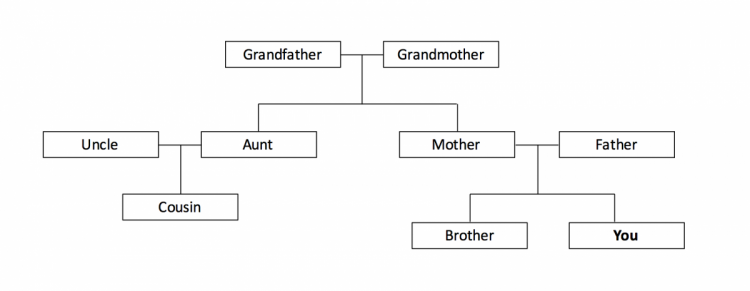

The example of a family tree

Here is a familiar example that everyone will know about – a family tree (Figure 4). You will probably already know how to interpret patterns of relatedness on a family tree, and it turns out that the same principles apply to phylogenetic trees more generally.

In Figure 4 we can see that you are more closely related to your brother than you are to your first cousin. Trace the tree back in time to your ancestors and you will see why. The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) that you share with your brother is your mother. In contrast, the MRCA you share with your first cousin is your maternal grandmother.

These principles also apply when you are reading more complex phylogenies – remember to trace back to MRCAs to examine patterns of relatedness.

A true tree?

The case of a family tree is a rare example where we typically know part of the true biological tree; we have a complete explanation of the genealogical relationships among family members. This is because we know:

- all of the ancestors and descendants who are or were recently living

- the identities of the biological parents of each child

Unfortunately, when we estimate phylogenies from present day sequences that are not so closely related, we seldom know the true tree. This is because we do not know what sequences occurred in the ancestors, and therefore what genetic changes occurred to make the sequences the way they are today. This is why we need methods of phylogenetic reconstruction to infer the true tree.