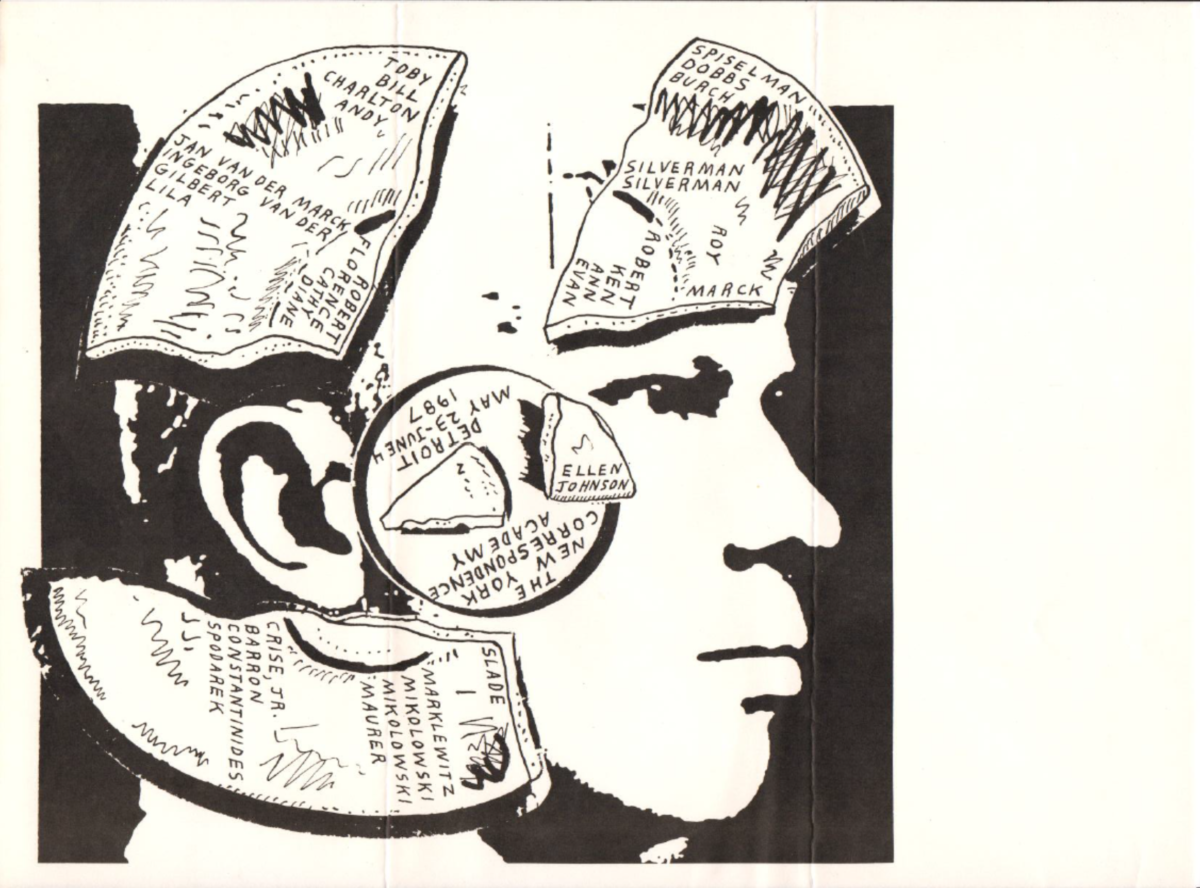

Fig. 1.

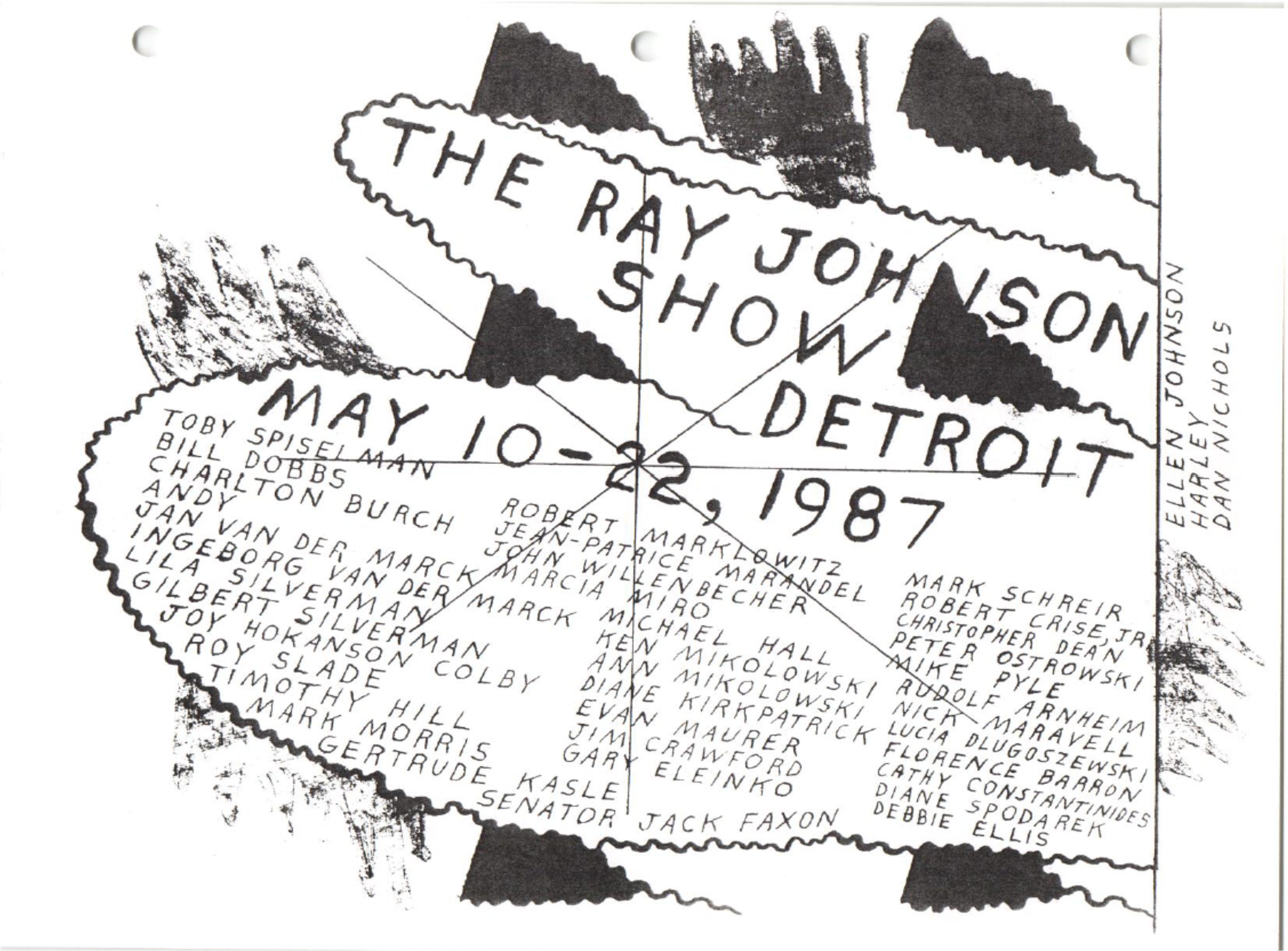

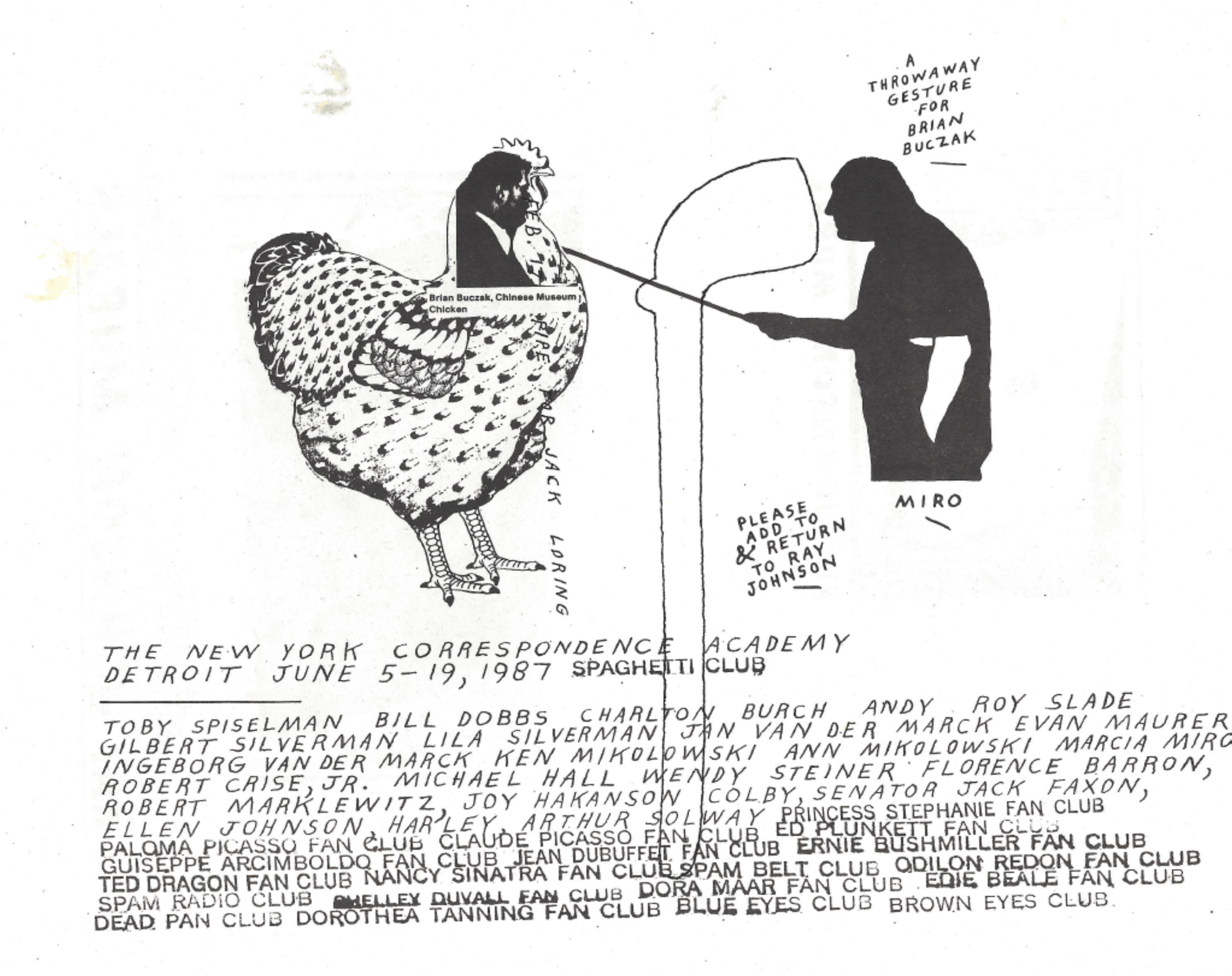

Ray Johnson, untitled mailing (The New York Correspondence Academy Detroit), May, 1987. © The Ray Johnson Estate.

The names on the flyer, in alphabetical order: Andy [no last name; see also Figs. 21 & 22], Florence Barron, Charlton Burch, Cathy Constanides, Robert Crise, Jr., Bill Dobbs, Ellen Johnson, Robert Marklewitz, Ken Mikolowski, Ann Mikolowski, Evan Maurer, Gilbert Silverman, Lila Silverman, Roy Slade, Toby Spiselman, Diane Spodarek, Jan Van Der Marck, Ingeborg Van Der Marck.

But before I get to the details of Ray Johnson’s story, including the occasion for this flyer, I want to linger for a while on that phrase, “art world.” If you’re reading this, it’s a term you likely know and use. It could be that you also know something of the extended debate among philosophers and sociologists about the meaning of the term, a debate provoked by a 1964 article by philosopher Arthur Danto (1924-2013; born and raised in Detroit, made his name in New York) titled, simply, “The Artworld.”1Arthur Danto, “The Artworld,” The Journal of Philosophy 61.19 (1964): 571-584. All subsequent references will be in-text. Of course, Danto didn’t coin the term; he picked it up in his wandering through New York galleries, in one of which he had a fateful encounter with Andy Warhol’s then newly minted Brillo Boxes. I feel this is art, he thought, but I can’t say why. The philosopher’s feeling set off a lifetime of speculation, centered on the critical insight that “To see something as art requires something the eye cannot descry - an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld.” (Danto, “The Artworld,” 580) For Danto, that is, “the artworld” is an intangible, an atmosphere composed of diffused particles of theory and knowledge about art; to breathe in that atmosphere enables one to see things differently than those who breathe the ordinary air, to see, for instance, objects that are indiscernible from commonly available commercial packaging as art.

Warhol’s Brillo Boxes heralded the onset of a Duchampian era in the visual arts, when the question of what does and doesn’t count as art came to dominate art practice. During this period, which has not yet ended, Danto’s insight, that “the artworld” can be defined as the horizon of an idea, has proven indispensable. At the same time, the lofty atmospherics of “The Artworld” practically begged to be brought back down to earth. In his 1974 essay, “What Is Art? An Institutional Analysis,” another philosopher, George Dickie, claims that “Danto points to the rich structure in which particular works of art are imbedded: he indicates the institutional nature of art.”2George Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis (Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press, 1974), 29. Italics in original. All … In fact, though, Dickie knew that Danto had never taken much philosophical interest in actually existing art institutions, and therefore took it upon himself to list the “bundle of systems” that constitute the artworld-as-institution - “theater, painting, sculpture, music, literature, and so on” (Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic, 33) - as well as some of the institution’s “core personnel,” “a loosely organized, but nevertheless related, set of persons including artists (understood to refer to painters, writers, composers); producers, museum directors; museum-goers, theatergoers, reporters for newspapers, critics for publications of all sorts, art historians, philosophers of art, and others” (Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic, 35-36). “And so on,” “and others”: Dickie’s descriptions of the artworld are more concrete than Danto’s, but still, as sociologist Howard Becker put it, “Philosophers tend to argue from hypothetical examples, and the ‘artworld’ Dickie and Danto refer to does not have much meat on its bones.”3Howard Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1982), 149. Becker himself made an effective start at fleshing out the aestheticians’ theories in his 1982 book, Art Worlds. He also corrects, thereby, the philosophers’ professional bias toward top-down thinking about social structures, suggesting that instead of privileging the roles played in the construction of art worlds by theorists and historians (Danto) or artists and museum directors (Dickie), we “think of an art world” in lateral terms, “as an established network of cooperative links among participants” (Becker, Art Worlds, 34-5).

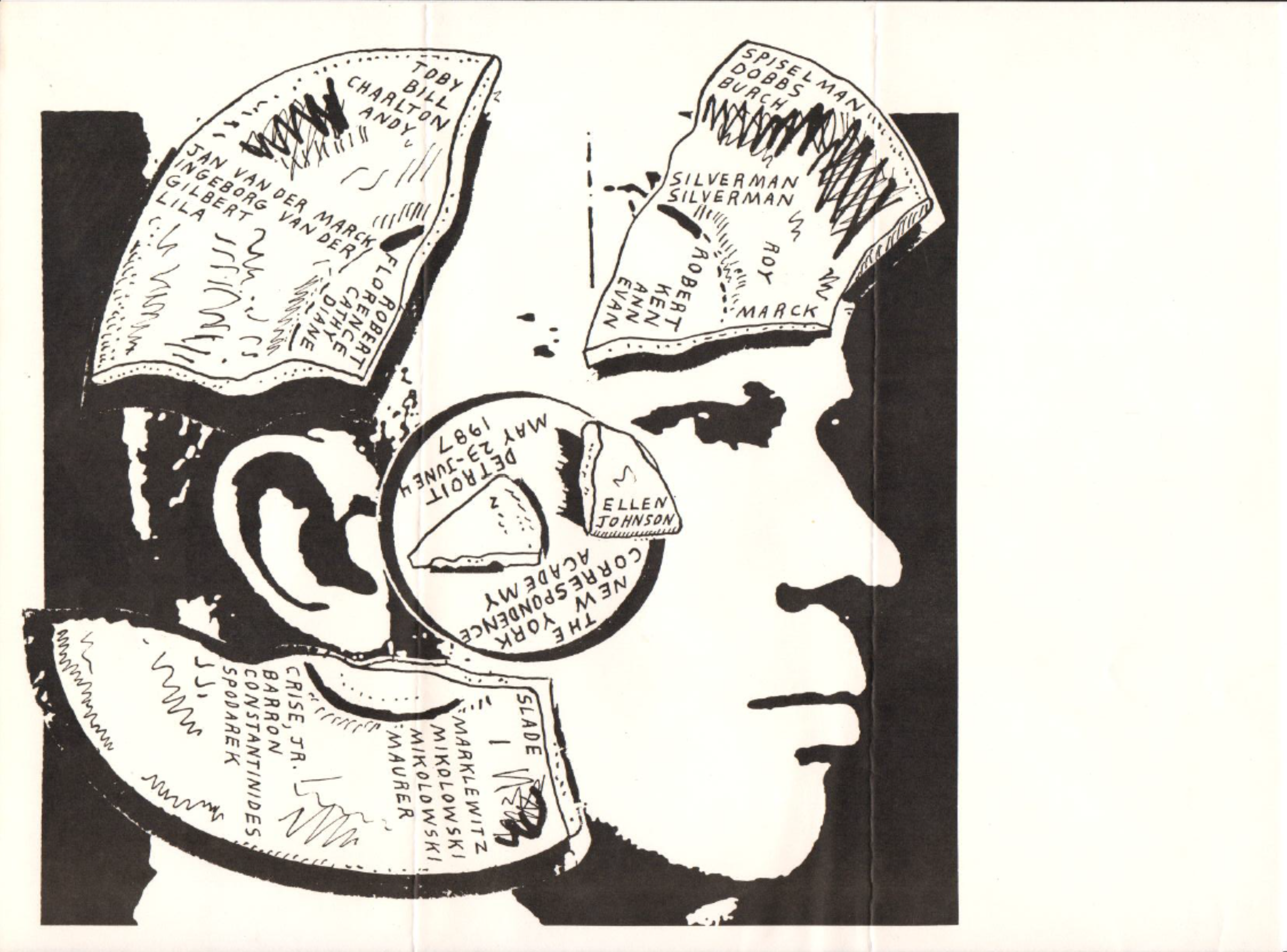

Fig. 2.

Ray Johnson, please-send-to included in mailing to Helen Jacobson. 1963 03-06, 63 03 06A, 2018.802.27.2, The William S. Wilson Collection of Ray Johnson, Ryerson & Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Art Institute of Chicago.

©The Ray Johnson Estate.

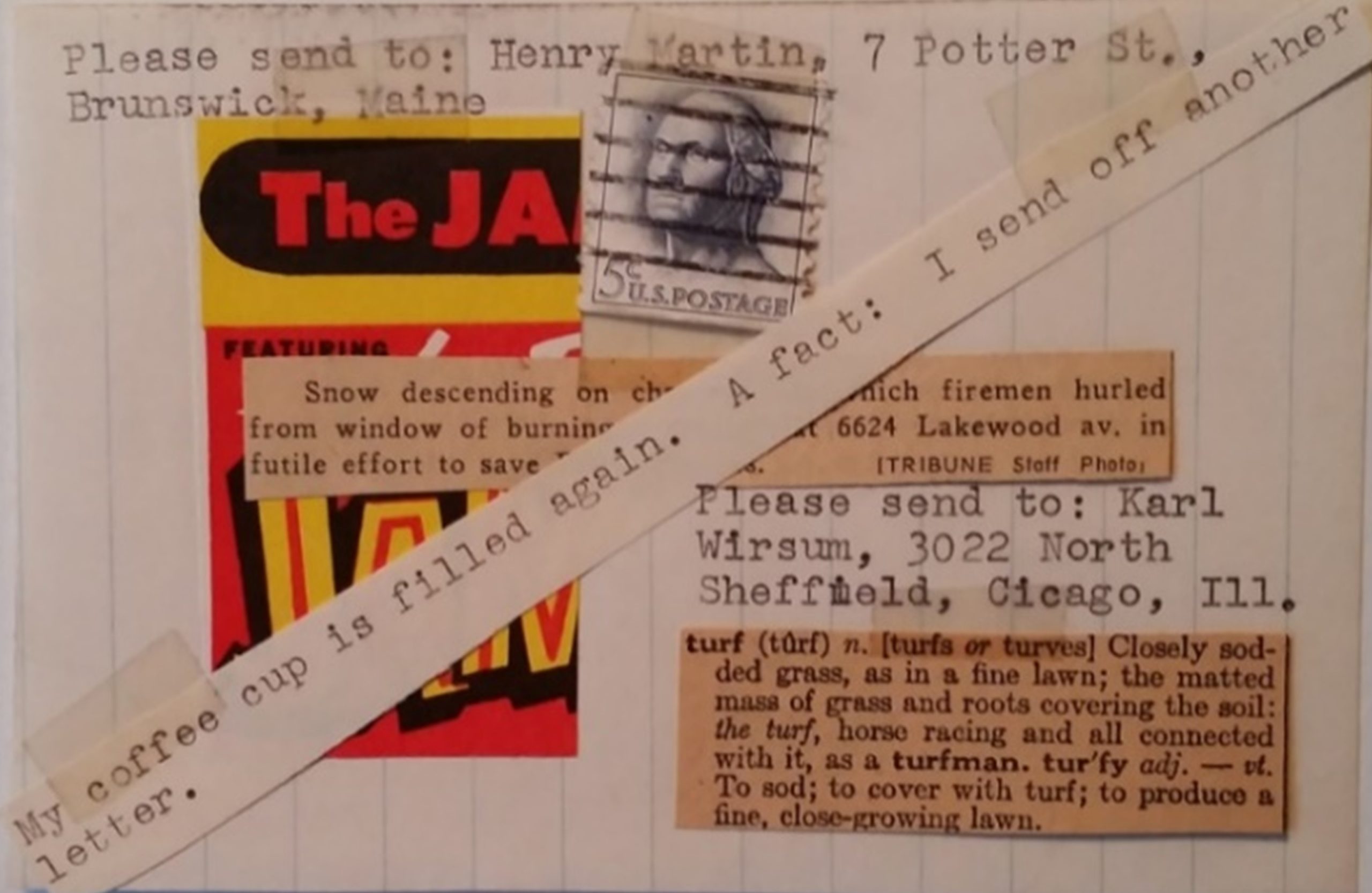

Fig. 3.

Ray Johnson, envelope included in mailing to John Willenbecher, 1967.

© The Ray Johnson Estate

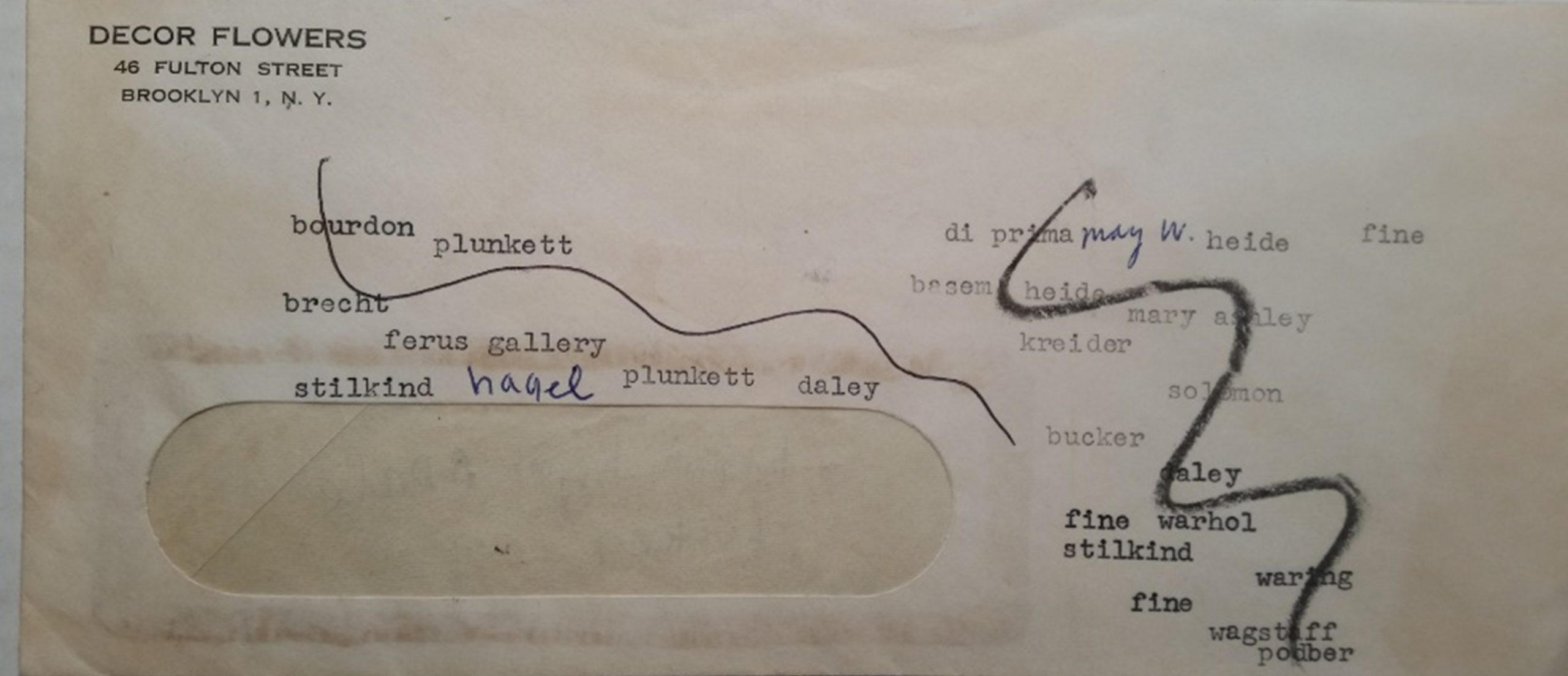

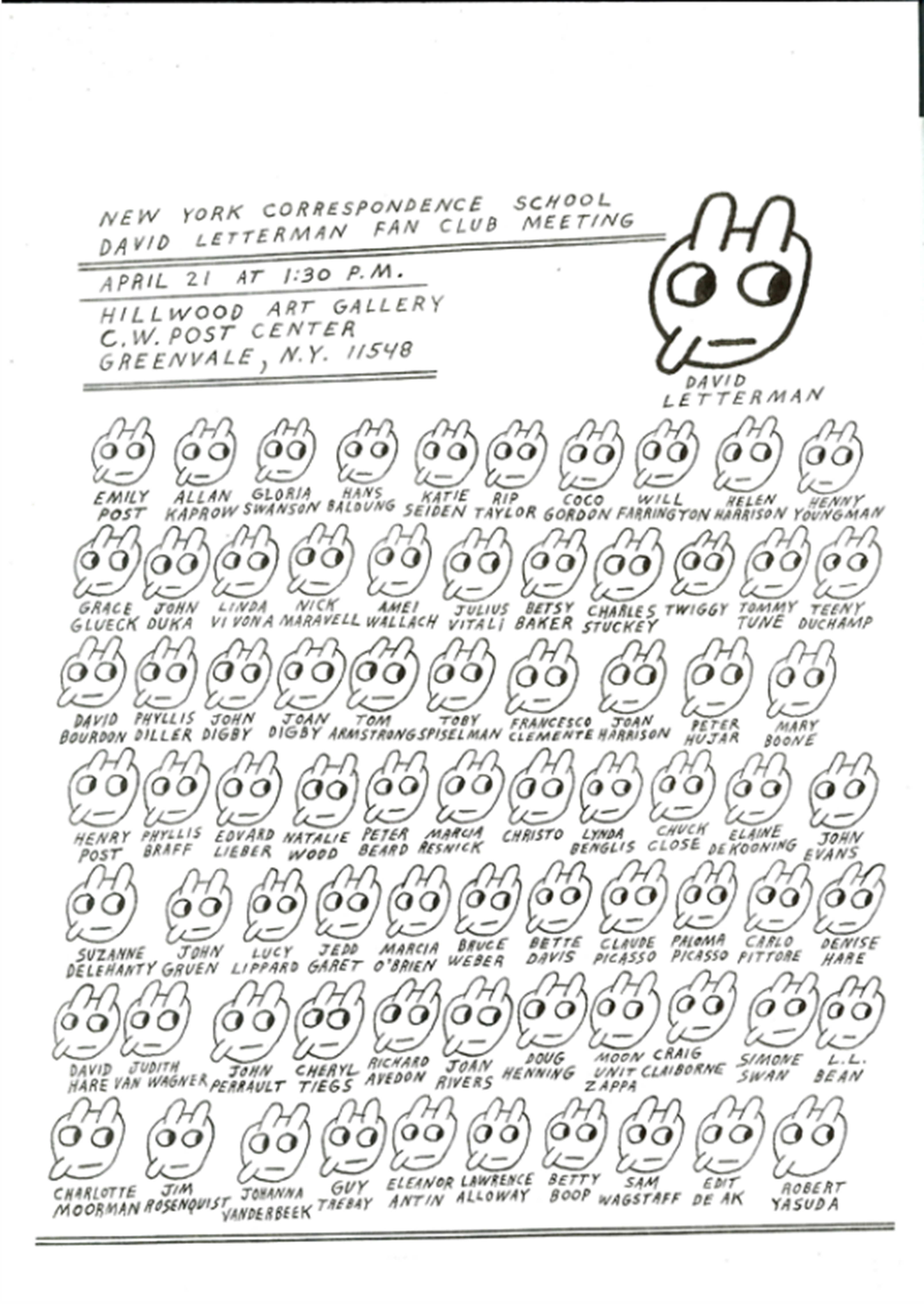

Fig. 4.

Ray Johnson, flyer for New York Correspondence School David Letterman Fan Club Meeting, 1983.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

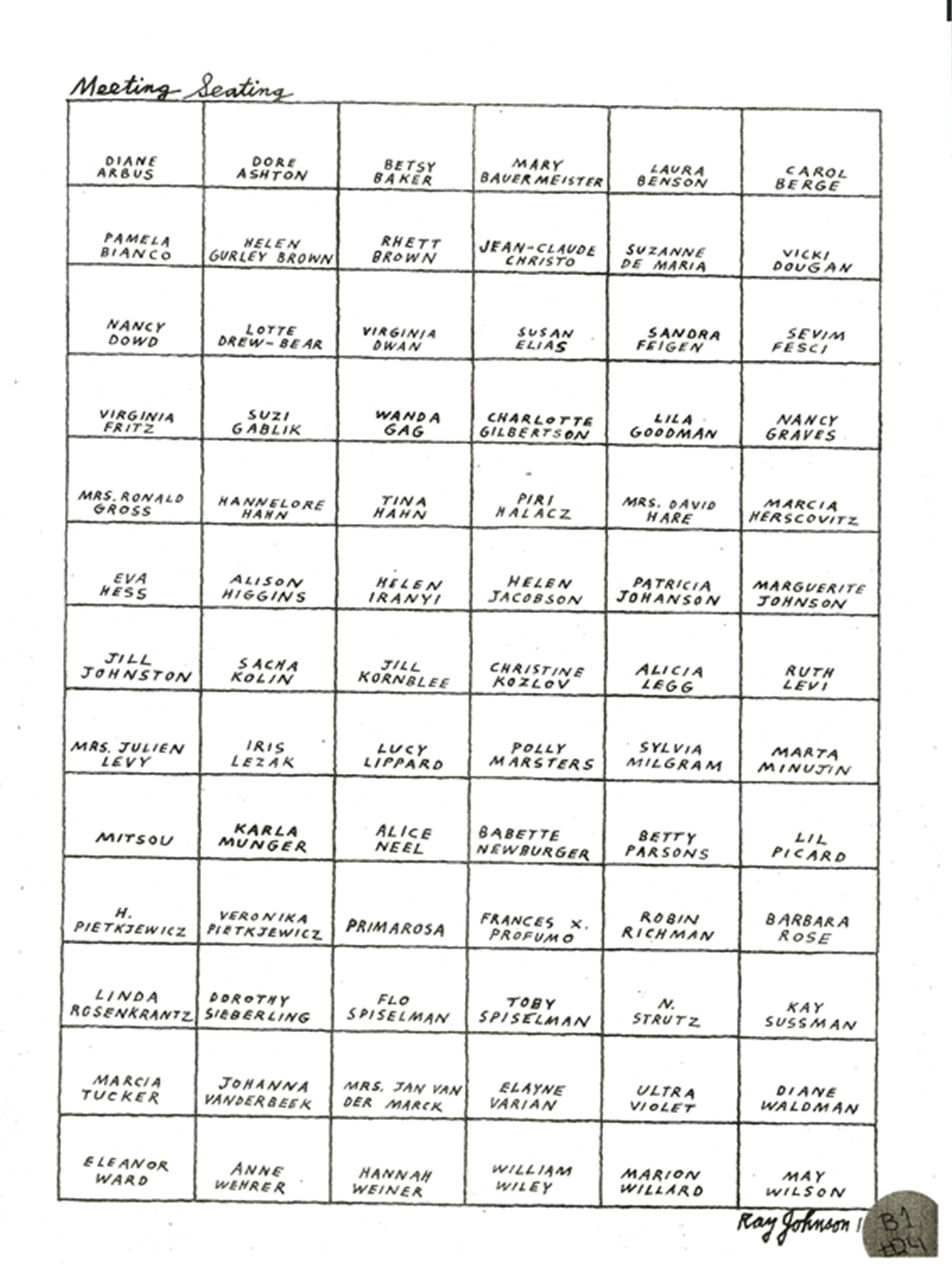

Fig. 5.

Ray Johnson, mailing (Meeting Seating), 1968.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

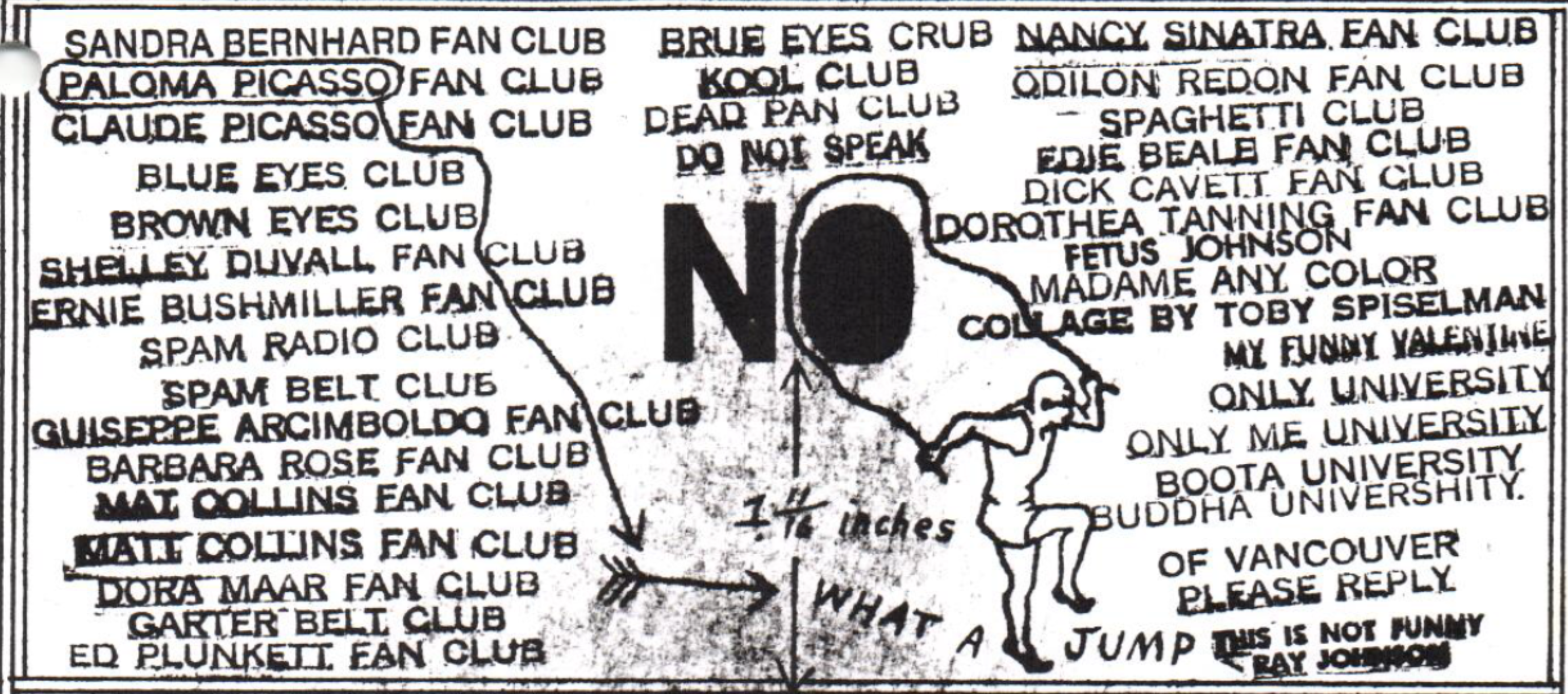

Fig. 6.

Ray Johnson stamp imprints, ca. 1984

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

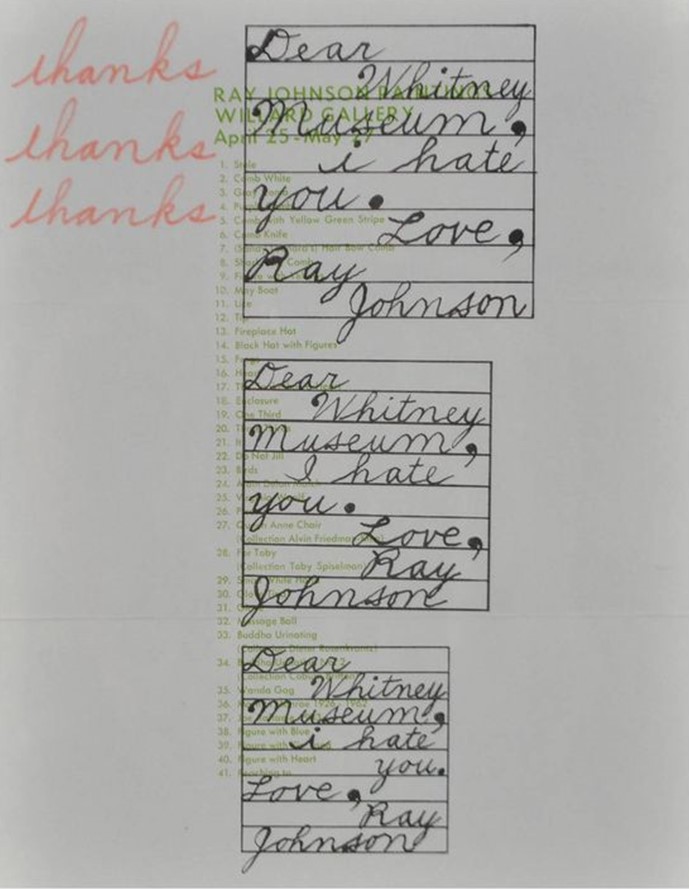

Fig. 7.

Ray Johnson, undated mailing (Dear Whitney Museum, i hate you. Love, Ray Johnson). Johnson sent out versions of this photocopy piece beginning in 1970, when the Whitney mounted a show of work by the members of Johnson’s New York Correspondence School.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

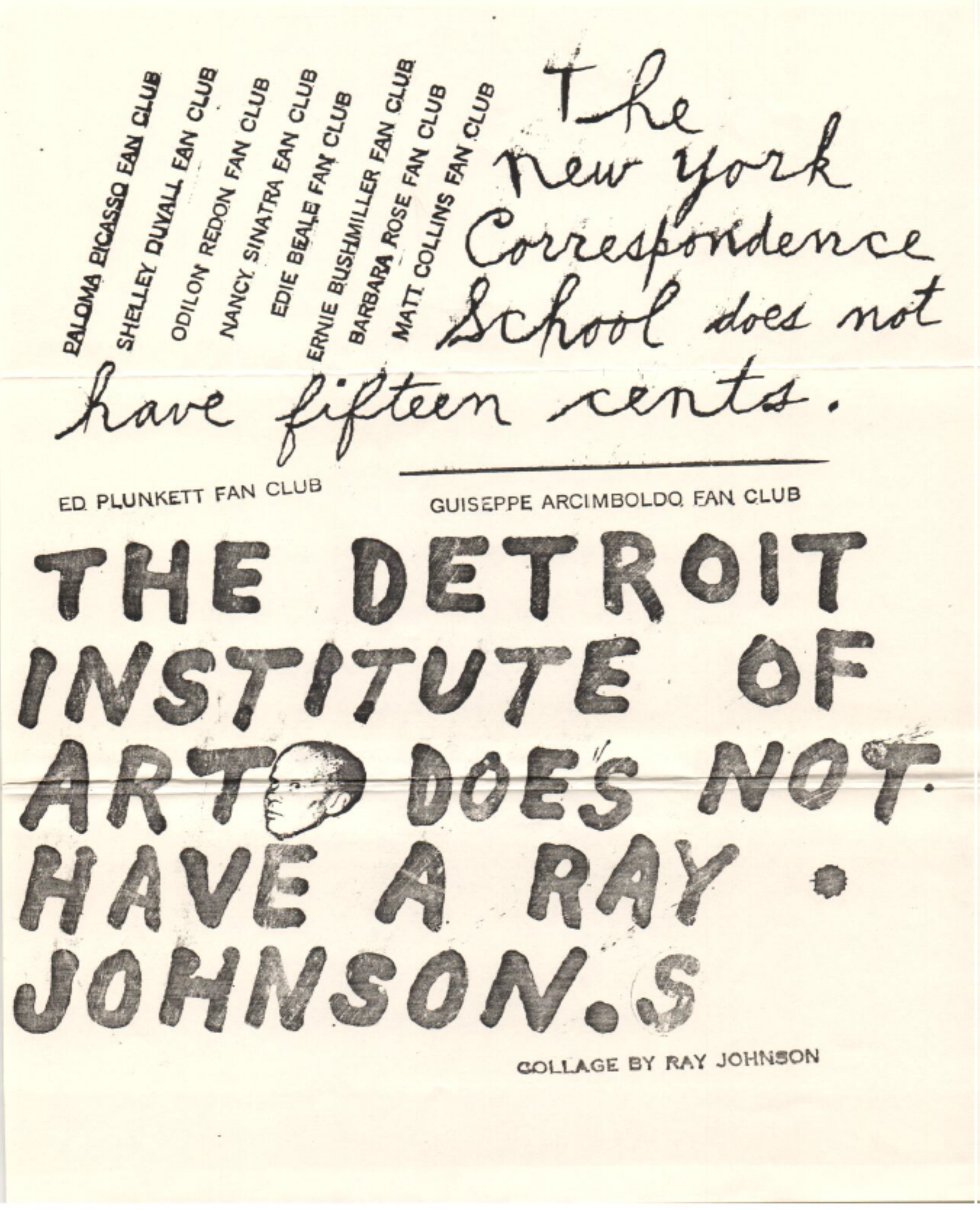

Fig. 8.

Ray Johnson, untitled mailing (The New York Correspondence School does not have fifteen cents), 1979.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

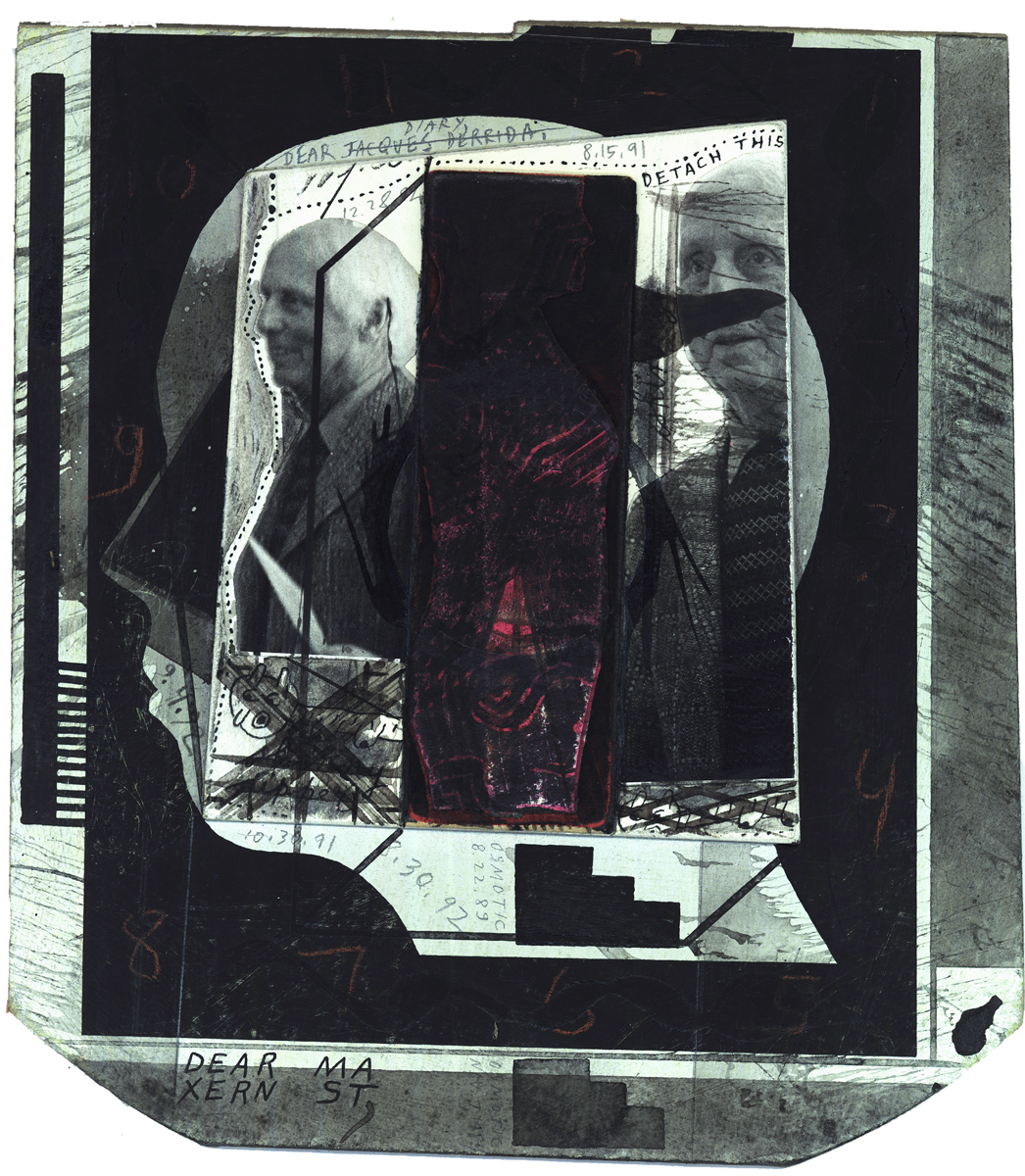

Fig. 9.

Ray Johnson, Untitled (Max Ernst with Toothbrush)

(Nov. 7, 1974-8.30.92-10.30.91-9.4.92-12.28.92-8.15.91).

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

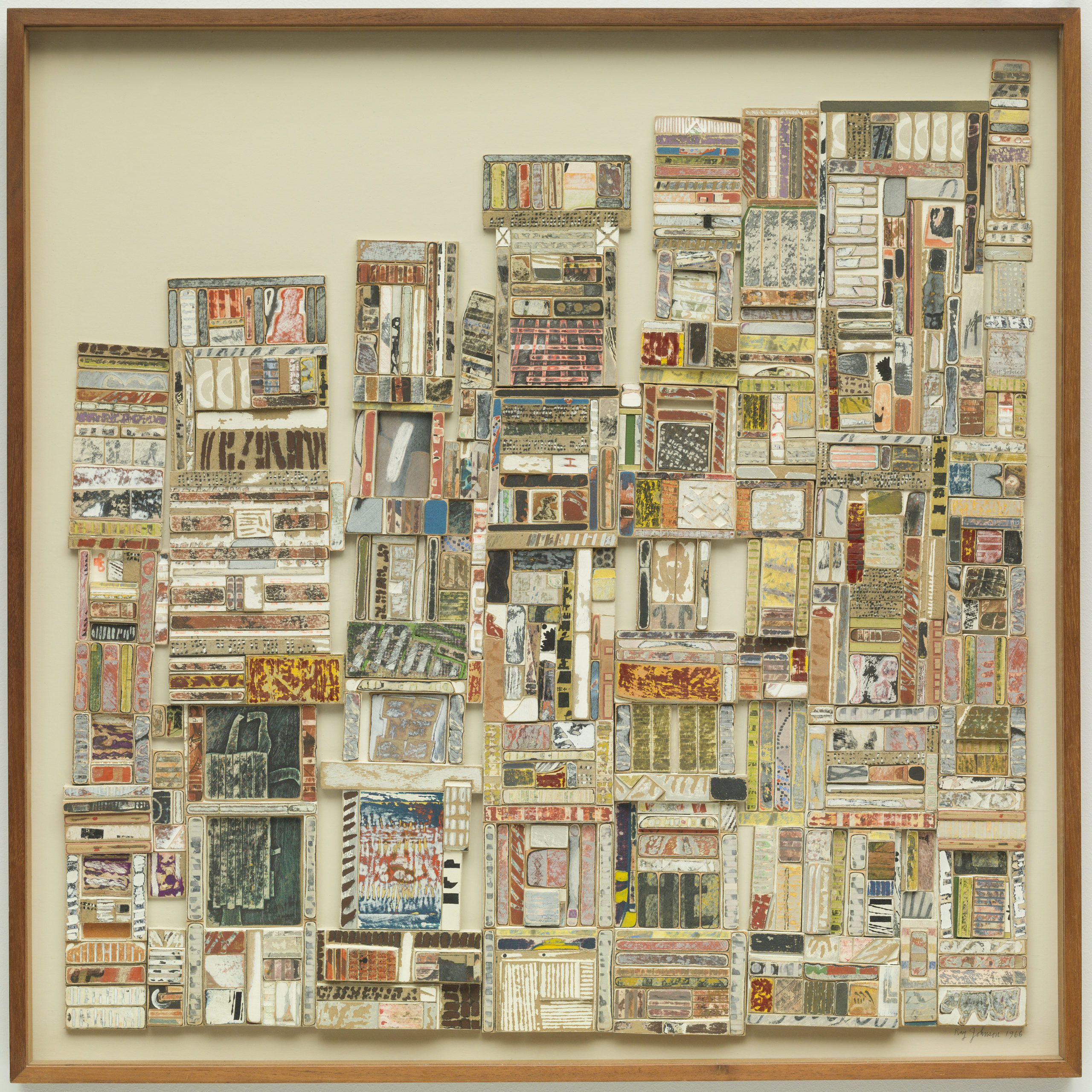

Rauschenberg’s answer, “I try to act in the gap between the two,” has a slightly desperate ring: if he is right, that art is a given reality just as life is, then the gap between them is a strictly notional place, reinvented by the artist each time he acts. The thought that art can’t be made drove Rauschenberg to expand his collage-work ever farther into three-dimensional space, on one hand, or, on the other, to dissolve it onto the immaterial surface of the silkscreen. For him, the gap between art and life is either an otherworld or a no-place. Johnson’s collage, however, holds to the confines of “the semi-three-dimensional,” which seemed to him somehow “more real.” For him, the bas-relief is a kind of materialized dialectic in which art presses outward from the ideal flats of painting only to be met by life’s immense counterpressure. Or, if we are using art-world terms, we might say that bas-relief is produced by the tension between Danto’s artworld-as-concept and Dickie’s art-world-as-institution. In any case, bas-relief may be said to be “more real” than art that is either ultra-flat or fully three-dimensional in that it is visibly a space of conflict: the artist’s room for maneuver is seen to be excruciatingly narrow. And yet, within the narrow confines of his chosen form, in the inch or so between the surface of the support and the protecting glass, Johnson managed to produce, in fact, delighted in producing, an astonishing variety of sculptural and painterly effects (Figs. 10, 11).

Again, in this kind of finely finished exhibition work, Johnson hewed closer to the dialectical pole of artworld-as-concept, while in his mail art, he engaged more directly with the pressure exerted by art-world institutions. In artists’ lives, such pressure manifests itself chiefly as a struggle for money and fame - a struggle that the radical democrats of mail art seek to evade through the free distribution of art, and the equal distribution of fame, throughout their networks. Johnson himself was in part this kind of utopian thinker, and in part a sociologist, a mordant analyst of “the rich structure in which particular works of art are imbedded.” Still, even at his most theoretical, or satirical, Johnson remained committed to art’s sensuous materiality, the formal, palpable manifestation of what Wallace Stevens called “a violence from within that protects us from a violence without.”8Wallace Stevens, The Necessary Angel: Essays on Reality and the Imagination (New York: Vintage Books, 1951), 37. A violence from within - for all their technical refinement, Johnson’s exhibition collages stubbornly fail to satisfy at least one of the art world’s most exigent demands: the rich variety of their bas-relief surfaces is almost impossible to capture in photographs. And Ray Johnson, the maestro of the Xerox machine, fully understood the implications of this fact, understood that modern art lives on and in photographic reproduction, or not at all; whereas Johnson’s art, even at its most sensuously palpable, remains oddly ephemeral. “ROBIN RICHMAN SAID PEOPLE IN HOUSTON CALL THEIR CHATEAUS SHADOWS,” reads a bas-relief placard in one collage (Fig. 12), which, together with the piece’s other semi-three-dimensional elements, casts a house-shaped shade on the support surface. My art lives, Johnson tells us, on and in shadows.

Fig. 10.

Ray Johnson, detail from Ice (1966).

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

Fig. 11.

Ray Johnson, detail from 24 Pork Chops (1969).

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

Fig. 12.

Ray Johnson, detail from Chateaus Shadows (1967).

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

I have described the social dynamic that mirrors the spatial dynamic in Ray Johnson’s art as a dialectical relation between artist and art world. Another way to phrase it might be that, for Johnson, personal history and art history are inextricably intertwined (hence Ray’s frequent references to Ellen Johnson, his art-historian doppelganger). Meanwhile, to speak of the artist’s personal history brings us back, at last, to Detroit, where Johnson first decided that he wanted to live for art. In 1945, his senior year at Cass Technical Institute, an article in the student newspaper described Johnson as “Outstanding in the Art Department,” high praise indeed in a school full of talented and competitive creative types. But while the teenaged Johnson was clearly devoted to creation, in this article, at least, he seemed ambivalent about competition. ‘“My greatest ambition,’ offered Ray wistfully, ‘is to buy a farm and live on it, and paint for the rest of my life.’”9A clipping of this story appears in Lightworks magazine’s Ray Johnson issue. Lightworks #22 (2000), 6. Instead, Johnson went directly from Cass Tech to Black Mountain College, where he was again surrounded by ambitious artists, and from there to New York City, where he became a fixture in the art world, a well-known character and gimlet-eyed observer, until 1968, when he withdrew to the Manhattanite’s equivalent of a farm, a house on suburban Long Island, and stayed there, making art, to the end of his life.

This nutshell biography points to a paradox. In some sense, the wistful would-be recluse of the high school paper could be said to be the “real” Ray Johnson, a person of whom everyone, including his closest friends, said, “No one really knew him,” who lived alone for most of his life, and in his last years saw few people day to day, other than his baffled but obliging postman. And yet, Johnson’s art is nothing if not social: the mailings incessantly circulated among hundreds of correspondents, from lifelong friends to distant strangers; the NYCS meetings and other participatory performances; the collages teeming with the names and images of people Johnson knew, or admired, or just found curious or funny or fascinating for some reason. By way of contrast, consider two artists in Johnson’s New York circle that he particularly admired, Jasper Johns and Agnes Martin, whose art, in Johns’ case deadpan-enigmatic, in Martin’s mystical-abstract, clearly reflects their reclusive tendencies. Johnson could have followed in their path - at Black Mountain, his favorite teacher was Josef Albers, and in college and just after, he painted geometric abstractions in the vein of Albers - but by the mid-nineteen-fifties, his work had taken its ineluctably social turn. Or perhaps, I should say, Johnson returned at this point to an aspect of his practice that he had never quite abandoned, but that he had not previously considered central to his work: correspondence.

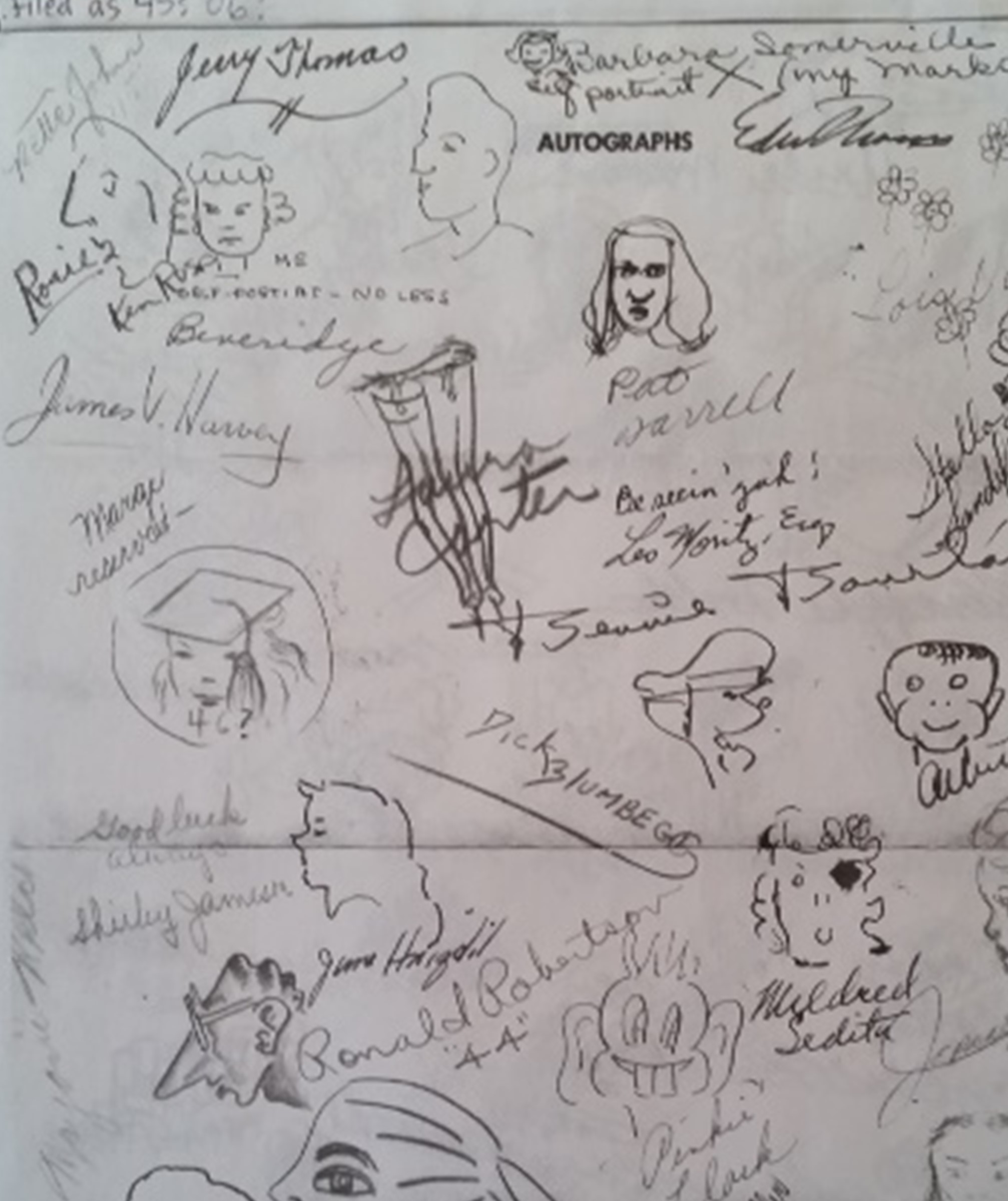

When Johnson’s high-school friend and fellow artist, Arthur Secunda, moved with his family to New York City in 1943, Ray began sending him daily letters that mixed images and words, drawing and collage. In later years, when asked about the origins of his Correspondence School, Johnson often cited these letters, and, certainly, the young Ray’s daily practice of corresponding, mixing of media, and antic humor would also come to characterize his mature work. But what made Johnson’s NYCS a notably innovative enterprise was the artist’s emphasis on correspondence as a means of networking; and the outlines of this project, too, I think, can be discerned as early as Johnson’s high school years, along with his dawning sense of the network’s complex relation to an art world. Take, for instance, the following passages from one of his letters to Secunda, undated but likely from the autumn of 1943:

Today is Friday and we have another art class at the institute tonight. I go to a sculpture class tomorrow morning.…We have a teacher, Mr. Smith from Wayne. He sure is a sharp guy - all the girls think so, too. Pete is in the class.

* * *

Please send me something that you did in your life class. Please send a drawing, not a cartoon. Your cartoons are swell, but you also can draw. Please follow my advice, son.

* * *

There is a Michigan Artist Show in the gallerys [sic] of the Institute now. I plan on seeing it tonight. On opening night, there were high class gents and dames in evening dress and George T. says that it was a classy affair.10A facsimile of this letter, along with other mail from Johnson to Secunda, is included in the loose-leaf catalogue, Correspondence: an exhibition of …

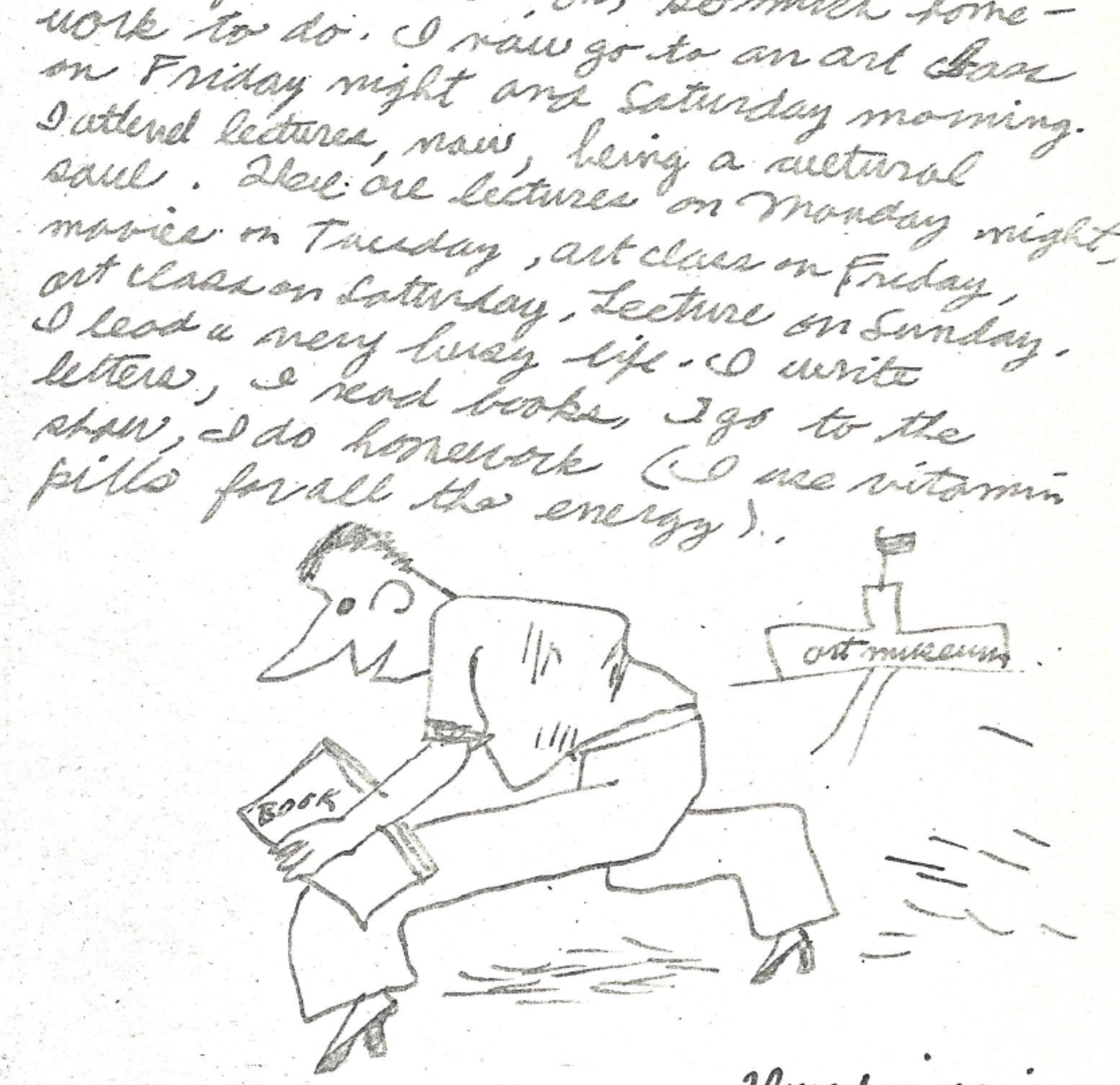

The “institute” is the Detroit Institute of Arts, which offered a robust educational program of which Johnson, together with artist friends from Cass Tech like Pete and George T., took full advantage: “There are lectures on Monday night, movies on Tuesday, art class on Friday, art class on Saturday, lecture on Sunday. I lead a very busy life,” a breathless Ray reports (Figs. 14, 15). The museum also made efforts to support local artists, including an annual juried show (the “Michigan Artist Show” referred to in the letter) presented in conjunction with the Detroit Artists Market, a non-profit gallery which is still in operation. The letters to Secunda register Johnson’s excitement as he begins to grasp the way high school connects to the museum which connects to the gallery which connects, somehow, to the world of “high class gents and dames in evening dress”; he is also beginning to sense how these institutional connections may help to solidify and extend the aspiring artist’s personal-professional relationships. “Please send a drawing, not a cartoon,” Johnson urges his friend. Even for goofballs like these two, art is turning into a serious business, and serious artists depend on one another for support and critique.

My sense is that Johnson learned the latter lesson when he began to move beyond his high school circle and connect with working artists in the community. You can see him striving to make the link between his social and proto-professional lives in a note preserved by Johnson’s closest friend at Cass Tech, Pete Di Cresce: “Pete - next Sat. nite [sic], I get out of work at 6 - I have to eat my supper downtown - why don’t we both go to the Russian Bear and have a good time and then go from there. Why don’t you bring something for Stan and Zubel to criticize. It’ll be a good criticism.”11DI CRESCE, Undated, 2018.802.12, The William S. Wilson Collection of Ray Johnson, Ryerson & Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Art Institute … The Russian Bear, a restaurant and nightclub, was a hangout for established artists on the Detroit scene like Sarkis Sarkisian, Zoltan Sepeshy, and Chico Lopez;12See Gordon and Elizabeth Orear, Sarkis (Detroit: Center for Creative Studies and Wayne State University Press, 1995), 73. the younger painters Zubel Kachadoorian and Stan Twardowicz (“my friend,” Ray calls him, proudly, in another note to Pete) were rising stars who would go on to have significant careers. Other traces of Johnson’s expanding world-view can be found in his high-school scrapbook: reviews of exhibitions at the DIA, curated by its cosmopolitan director, William Valentiner; clips chronicling shows by local luminaries like Kachadoorian, Twardowicz, Lopez, and Edgar Yaeger at Detroit Artists Market and two other pillars of the burgeoning Detroit art scene, the Scarab Club and the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts (now - as you may know - the College for Creative Studies); a receipt for one of Johnson’s own drawings, submitted to the Artist’s Market; a newspaper story about the Ox-Bow School of Art in Saugatuck, Michigan from the summer of 1944, when Johnson attended, along with several of his Cass Tech friends, and Twardowicz and Kachadoorian were among the teachers. That summer at Ox-Bow, Johnson also made a fateful new connection, befriending Elaine Schmitt, whose sister Elizabeth had enrolled the previous year at Black Mountain College, and who ultimately convinced Elaine and Ray that they should apply there, too (Fig. 16).

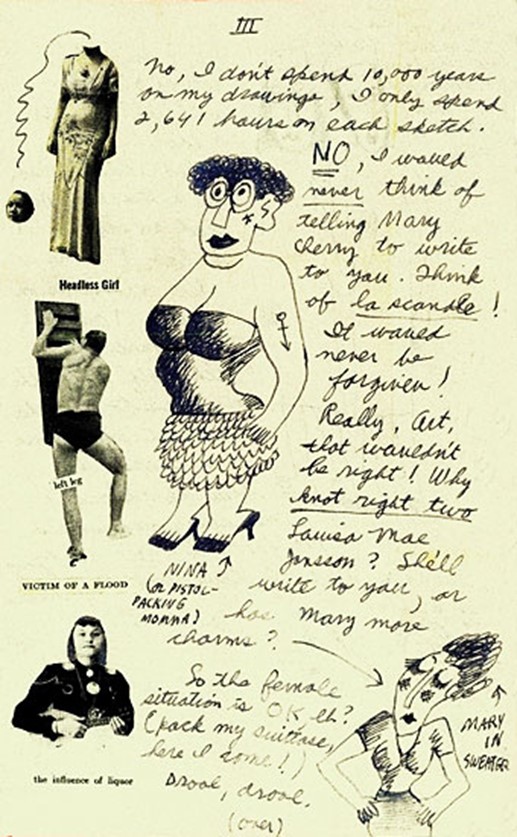

Fig. 13.

Ray Johnson, collage-letter to Arthur Secunda, 1943.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

Fig. 14.

Ray Johnson, detail from letter to Arthur Secunda.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

Fig. 15.

Ray Johnson, page from a high school sketchbook.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

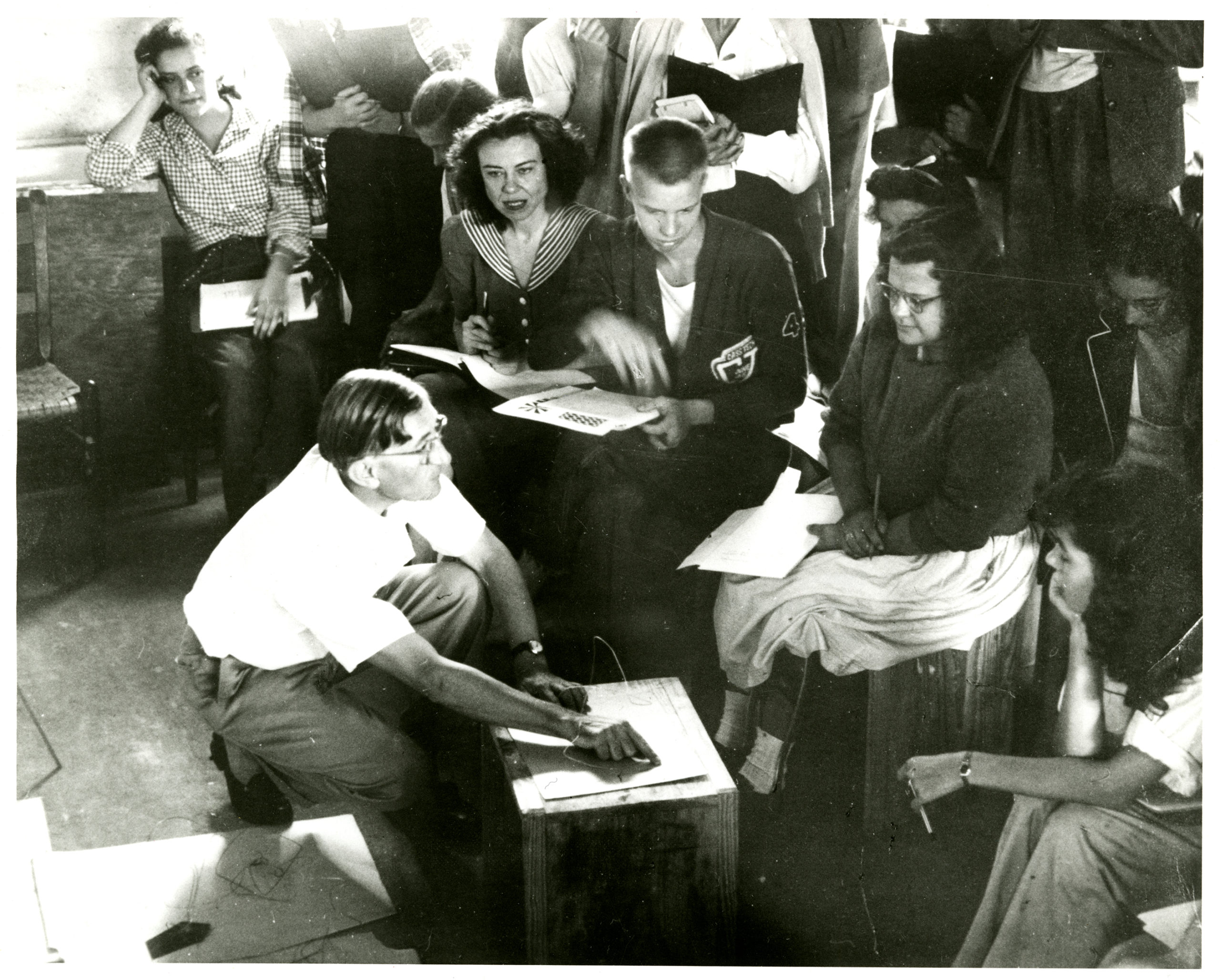

Fig. 16.

Ray Johnson (r., in Cass Tech sweater) in Josef Albers’ class, Black Mountain College.

Courtesy Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina.

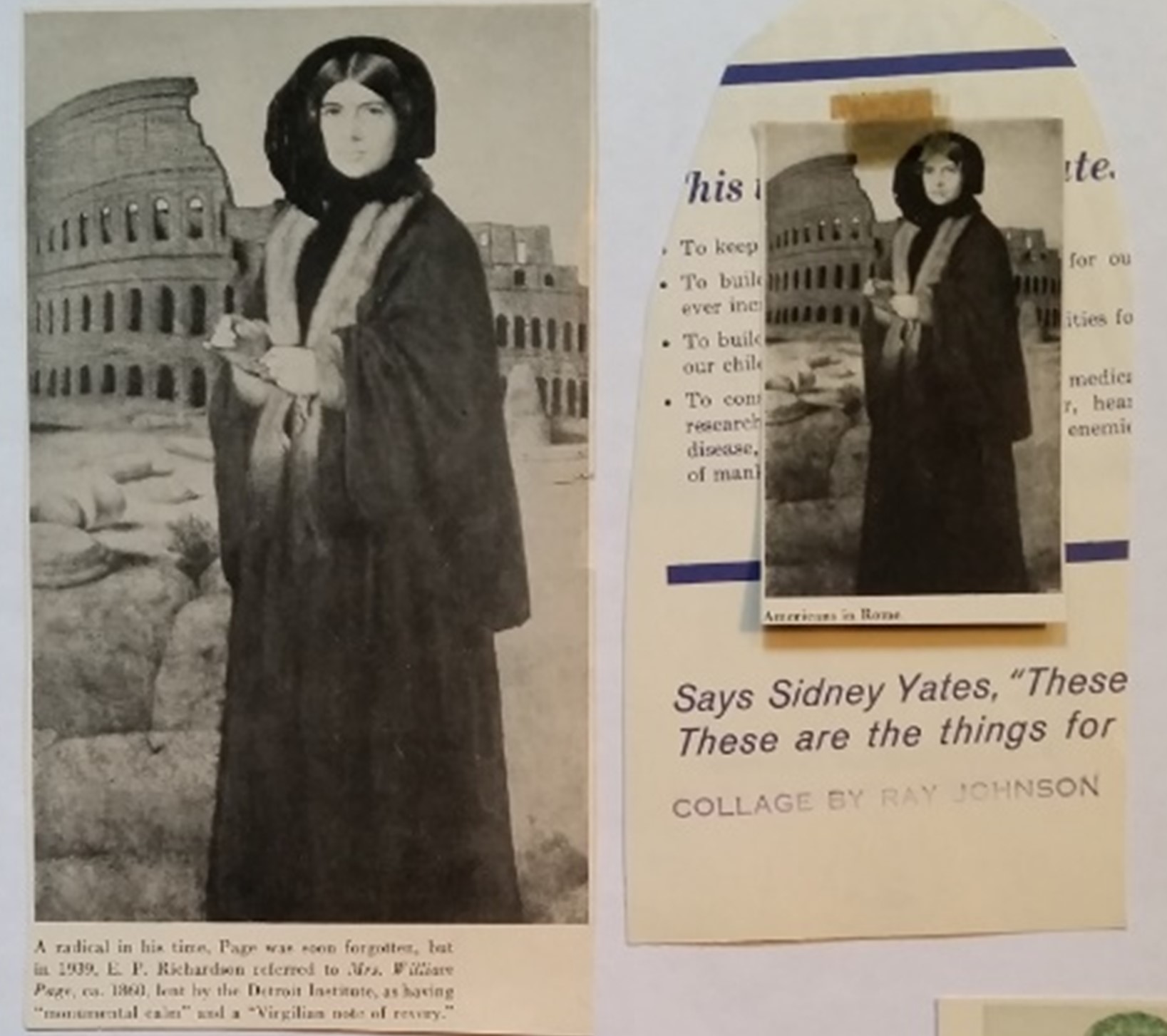

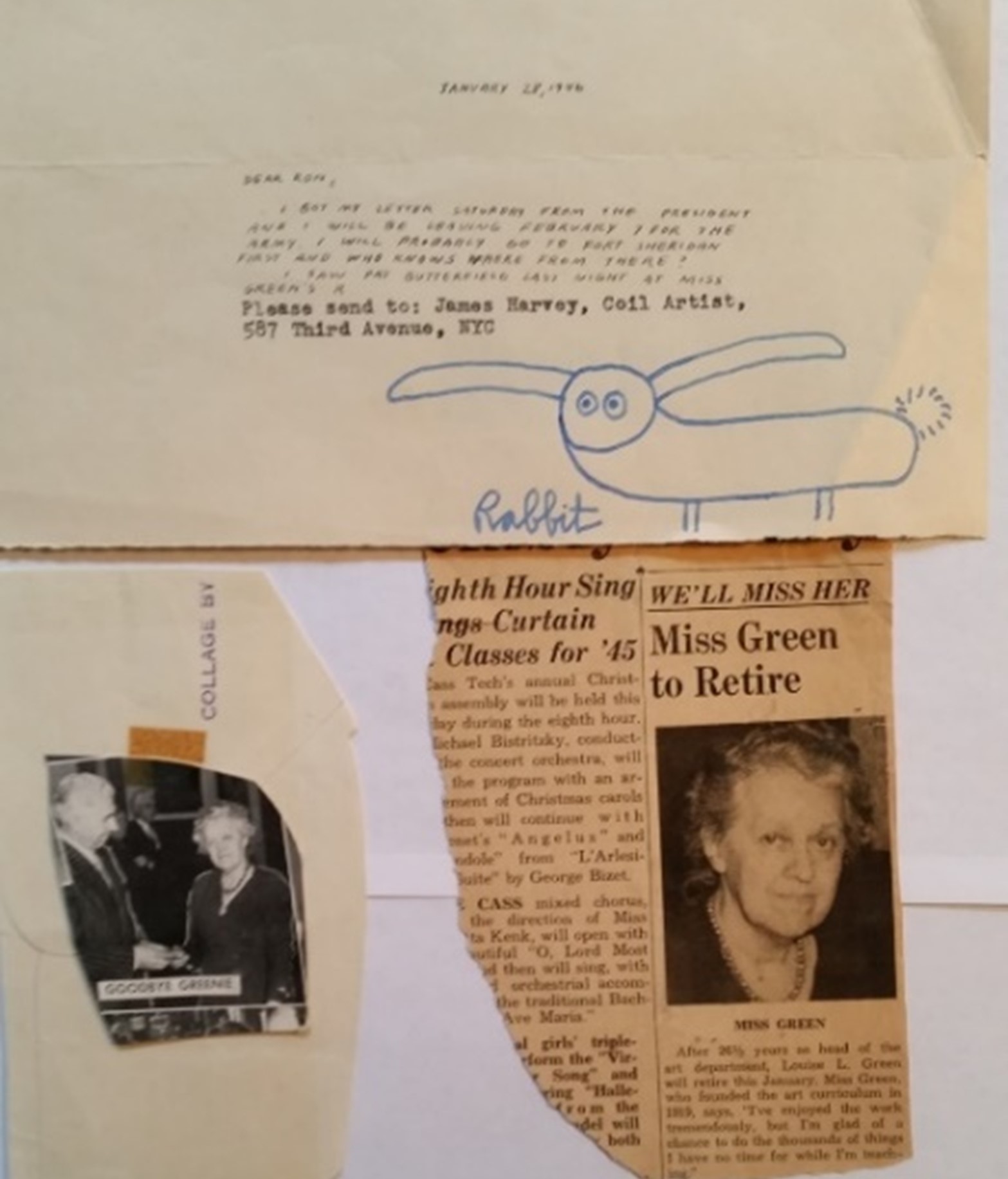

Fig. 17, 18, & 19.

Ray Johnson, three pages from a please-send-to for James Harvey via William S. Wilson. 1965 06-12, Around 65 07 15?, 2018.802.42.5, The William S. Wilson Collection of Ray Johnson, Ryerson & Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Art Institute of Chicago.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

Fig. 20.

Ray Johnson, Jan/Feb (1966). The Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, Elinor Kushner Memorial Fund.

© The Ray Johnson Estate

Johnson’s shortlist of works here perfectly encapsulates Valentiner’s values, representing art derived from near and far, past and present, institution and community—this last embodied, for Johnson, by Richard Lippold, Johnson’s longtime lover, whose art world connections helped ease shy Ray’s transition to life in New York. The “Dr. Valentiner” letter is part of a “please send to” packet directed to Johnson’s high school classmate and fellow Manhattanite James Harvey, an abstract painter and graphic artist who is best remembered as the designer of the original—that is, Brillo’s own—Brillo Box.15Ray Johnson please-send-to for James Harvey via William S. Wilson. 1965 06-12, Around 65 07 15?, 2018.802.42.5, The William S. Wilson Collection of … The mailing includes two clippings about a Cass Tech art teacher, Miss Green, a fragment of a note in Johnson’s hand from 1946, a yearbook page with the teenaged Harvey’s signature, and two images of a portrait from the DIA’s collection (Figs. 17, 18, 19). This mailing, as Johnson knew, would never reach Harvey, who died of cancer in July of 1965; it was a kind of memorial, both for Harvey himself and for their shared childhoods.

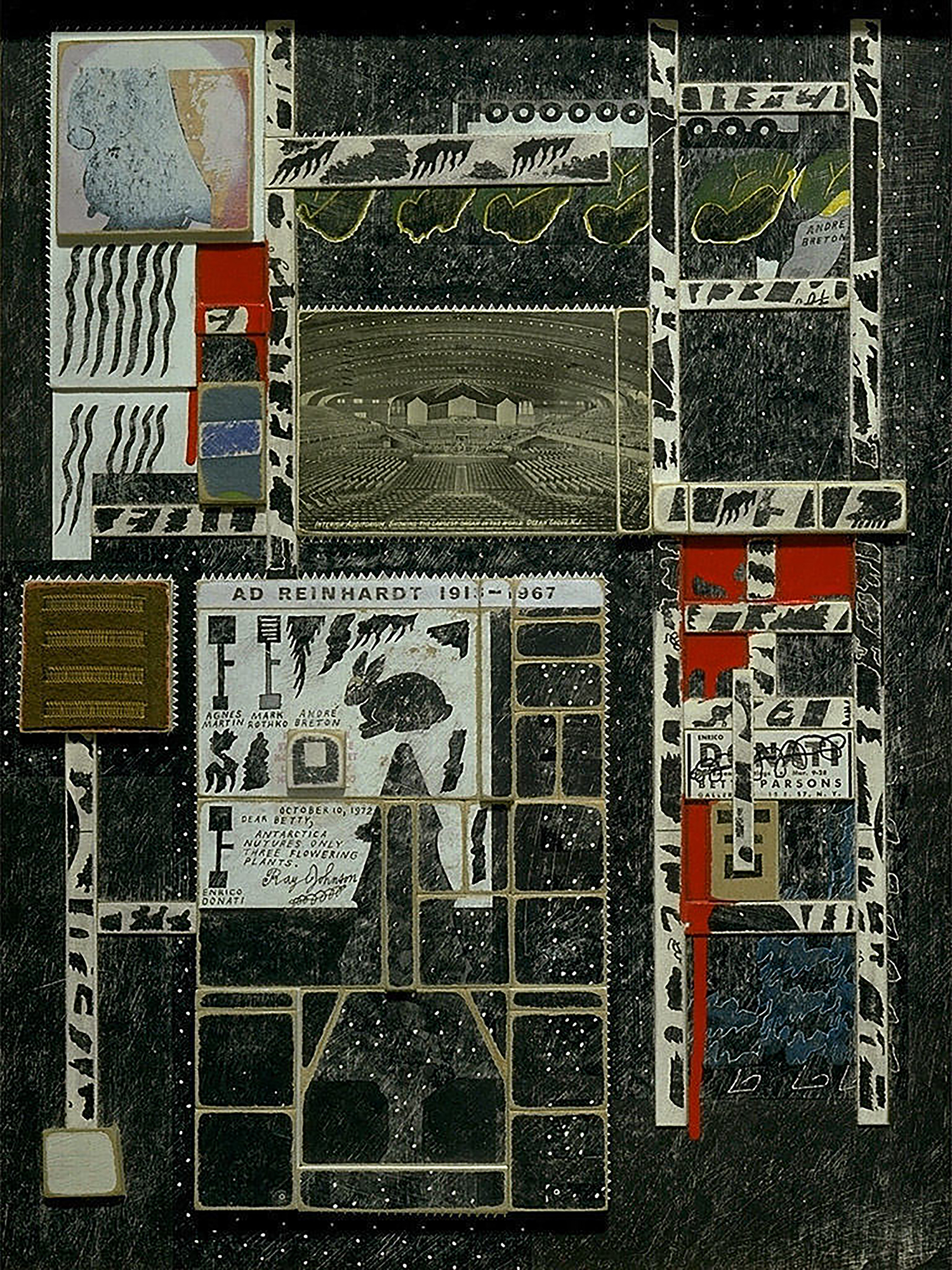

1965 was also the year that Johnson had his first solo show at a New York gallery, at the somewhat belated age of thirty-seven. (He achieved a certain cult success rather quickly, but the institutions of the art world were slow to recognize him.) Within a few years after this first flash of public recognition, Johnson’s sense that the art world, in all its aspects, was his true subject had crystallized, as had his artistic style. The collages that appeared in the spate of solo shows that came Johnson’s way after 1965 were, as one of his friends wrote to another in 1966, “freer than last year, and less dependent on a single major shape.”16Letter from George Ashley to May Wilson, 1966 01-07, 66 04 27, 2018.802.43, The William S. Wilson Collection of Ray Johnson, Ryerson & Burnham … Johnson, in other words, had abandoned the principle of gestalt composition and reconceived collage as a fundamentally mobile medium, in which semi-three-dimensional parts could be subject, in theory at least, to perpetual re-arrangement. The space of the image became a field of free associations, where networks could form and reform, “like people in a kaleidoscope.” One of Johnson’s first successful works in this new kaleidoscopic mode was January/February, dated 1966 (Fig. 20). The first real-world Meeting of the New York Correspondence School took place two years later, in 1968; and, while the art world had been front and center in his work for some time, Johnson staked his first public claim to be its official historian with a 1973 show titled, “Ray Johnson’s History of the Betty Parsons Gallery,” which legendary gallerist Betty Parsons herself had the wit to host (Fig. 21).

As I have mentioned, though, Johnson moved away from New York City in 1968, which is to say, just as its art world had begun to come into focus in his art. One needs some distance to see things whole. This distance must be internal as well as external: it may be that only a born recluse like Ray Johnson would take the ever-shifting social landscape of the art world as his Mont Sainte-Victoire; and it may be that only provincials, like Johnson and Arthur Danto, would devote their lives to developing a theory of the New York art world. Or, perhaps, not just any provincials, but those who hailed from some place with an art world of its own - not “the” art world, just enough of one, a small but vital version still in its formative phase, when the would-be theorist could take in all the significant people and institutions and events at a glance.17Thanks to Gregg Horowitz for this crucial insight.

Fig. 21.

Ray Johnson André Breton (1972); with note to Betty Parsons and Parsons Gallery announcement. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Bequest of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1986.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

Fig. 22.

Ray Johnson, untitled mailing (The Ray Johnson Show Detroit), May 1987.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

Fig. 23.

Ray Johnson, untitled mailing (The New York Correspondence Academy Detroit), June 1987.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

Fig. 24.

Ray Johnson, untitled mailing (The New York Correspondence Academy Detroit), detail.

© The Ray Johnson Estate.

References