Tooth in poo suggests ancient shark ate its young

- Published

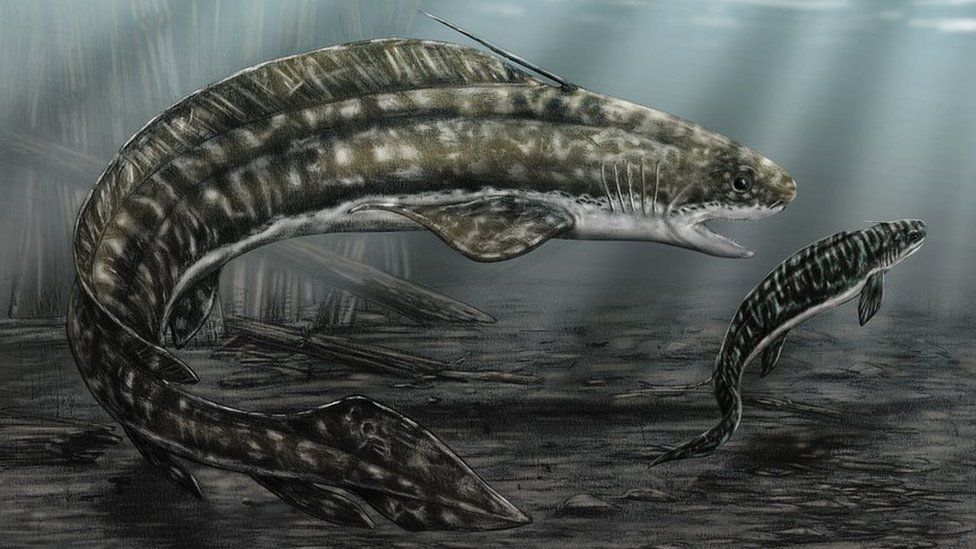

Orthacanthus was up to 3m long, with a large dorsal spike and forked teeth

Scientists have discovered a baby tooth in the fossilised faeces of a prehistoric shark, and concluded that the animals ate their own young.

This rare evidence of "filial cannibalism" was only revealed because the shark's corkscrew-shaped rectum produced dung in a distinctive spiral.

One such dropping, collected in Canada, holds a tiny tooth of the same species.

These Orthacanthus sharks lived in coastal swamps and may have resorted to cannibalism as they expanded inland.

Swampy sharks

The macabre sample was gathered by University of Bristol masters student Aodhan Ó Gogáin, now studying for a PhD at Trinity College Dublin, as part of a wider investigation into prehistoric fish on the coast of New Brunswick.

Like much of North America and Europe, this land used to sit near the equator and was thick with tropical jungles.

What was trees and swamps 300 million years ago is now coal-rich rock; the fossils in Mr Ó Gogáin's study come from the reclaimed site of North America's oldest coal mine, opened in 1639.

He said the highlight of his research, published in the journal Palaeontology, external, is definitely the notion of prehistoric cannibal sharks.

The shark's "coprolites" have a distinct spiral shape

"Other people have looked at their diet and found that their stomach contents contained little amphibians," Mr Ó Gogáin told the BBC.

"And there's also evidence that these sharks ate other genuses of xenacanth shark. But this is the first bit of evidence we have that they were eating their own young as well."

The claim for cannibalism rests on two distinctive aspects of Orthacanthus biology.

Firstly, its unusual shape means the fossilised poo, known as a "coprolite", can be conclusively identified as belonging to one of these large, freshwater sharks.

Secondly, the little tooth that was revealed when the researchers cut into the coprolite is also identifiable.

"These sharks have very distinctive tricuspid teeth, where they have little tusks coming up from the tooth," said Mr Ó Gogáin. "We're fairly confident of this discovery."

This section of a coprolite revealed a juvenile three-pointed tooth

The evidence is not unprecedented, he added; modern-day bull sharks, which occupy a similar niche in coastal swamps and shallow seas, have been known to feast on their young when necessary.

"Sharks tend to have a wide dietary range. They're not really picky eaters."

Eel meat again

Study co-author Dr Howard Falcon-Lang from Royal Holloway University of London said the discovery suggested the eel-shaped sharks - apex predators of their ecosystem - were facing a food shortage.

"There's cannibalism and then there's specifically filial cannibalism. And that is relatively unusual," he told BBC News.

"We generally find it in rather stressed ecosystems, where for whatever reason, food is running scarce. Obviously it's evolutionarily a bad move to eat your own young unless you absolutely have to.

"But in these 300 million-year-old ecosystems we're finding evidence for filial cannibalism quite commonly, based on the coprolite remains."

Samples were gathered from a reclaimed coal mine in New Brunswick, Canada

This period was a time of invasion, Dr Falcon-Lang explained. The land was rich in plants but not yet well stocked with animals, and aquatic beasts like these sharks were expanding their territory into fresh water.

"Part of this story, we think, is that during this invasion of fresh water, sharks were cannibalising their young in order to find the resources to keep on exploring into the continental interiors."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external