When most people hear “asexual reproduction” (offspring that come from a single parent) they think of single cells splitting in half, or maybe clonal plants. But did you know there are asexual lizards? Whiptail lizards (genus Aspidoscelis, formally Cnemidophorus) are common in the Southwestern US and Mexico and about one third of the 50-ish species are all female.

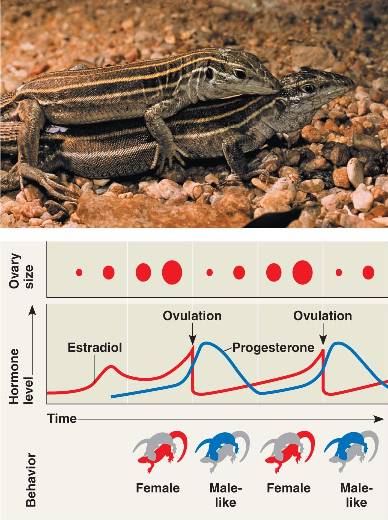

These Whiptail lizards undergo parthenogenesis – the growth and development of an embryo from an unfertilized egg cell. Other species reproduce this same way (some plants, aphids, and bees, for example), but these all-female lizards are unique in that they still (sort of) mate. Some females will mount other individuals, bite their shoulders, and entwine their tails – behavior that mimics the mating behavior of closely related, sexually reproducing lizards. Interestingly, this behavior seems to have an adaptive function; females that have been mounted by a “male-like” individual have increased reproductive success! This pseudocopulatory behavior seems to be mediated by hormones. Male (progesterone) and female (estradiol) hormones cycle with corresponding male and female-like behaviors (see figure below).

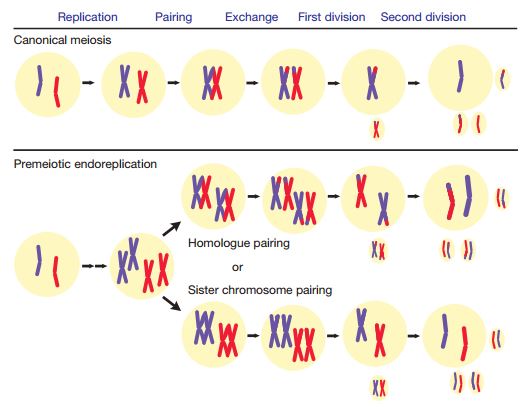

Like most asexually reproducing organisms, these lizards encounter a huge evolutionary roadblock: reduced genetic variation. If all of your children are direct clones of you, a single genetic mutation could make you all susceptible to disease. Or, a single environmental change that you aren’t adapted for could wipe you all out (read more: here). So how do Whiptails deal with this problem? These particular lizards are hybrids of other species, which gives them a lot of genetic variation to start with. They also undergo an altered meiosis, which lets them scramble some of their genes around before passing them on to their daughter, so they aren’t all direct clones. If you’re interested in how this altered meiosis occurs, check out the figure below, from Lutes et al. 2010.