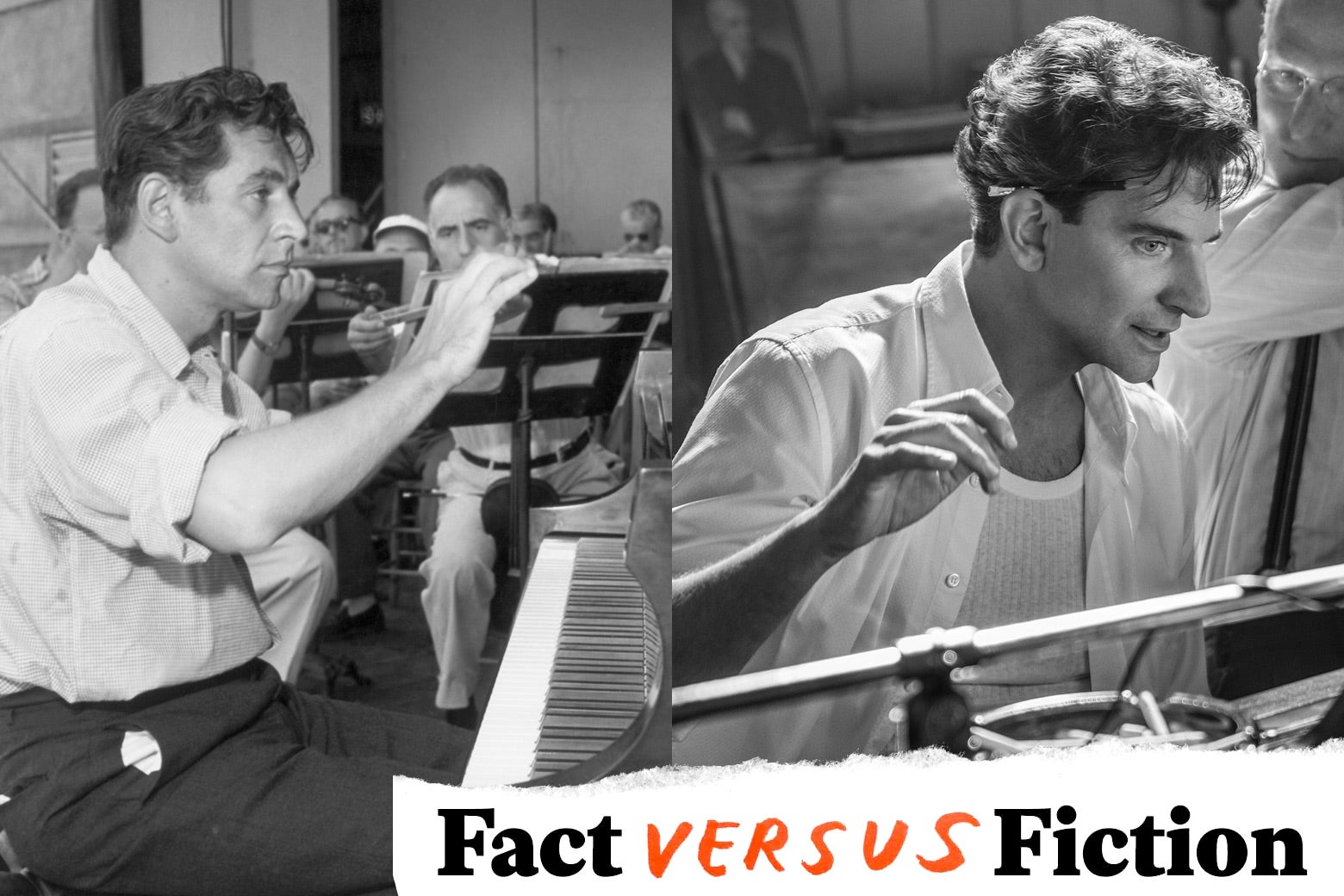

Leonard Bernstein, perhaps the best-known midcentury American conductor, is having a bit of a moment. There was last year’s Tár, in which he was referred to as the mentor/role model inspiring the would-be conductor, and now with Maestro, he has a biopic of his very own, directed, co-written (with Josh Singer) by, and starring Bradley Cooper.

The film starts with a quote from Bernstein: “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them, and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.” The primary tension Maestro is interested in exploring is between Bernstein’s loving and committed marriage to actress Felicia Montealegre (which produced three children he was devoted to) and his complex sexual identity, which included relationships with many men.

A secondary tension is between Bernstein the conductor, who enjoys public acclaim and is a self-confessed people person, and Bernstein the composer, who requires solitude in which to work. Finally, there is the tension between Bernstein the composer of acclaimed musicals like West Side Story and the Bernstein who dismisses this work as lightweight and feels he should be devoting himself to composing serious symphonic works (although his efforts in this area are generally met with less acclaim). But as Felicia says after watching a wonderful rehearsal of the ballet Fancy Free (which provided the basis for the musical On the Town and its film adaptation), “Why would you want to give this up?”

With a relentless focus on the marital relationship, Cooper dispenses with many of the traditional biopic whistle-stops. Anyone who is interested in either Bernstein’s or Montealegre’s backgrounds had better play close attention to a scene where they retreat to a quiet room at a party and rattle off each other’s minibios at speed. The two get engaged and suddenly it’s four years later, and we’re in the family apartment where the actual Edward R. Murrow is on the soundtrack, listing Lenny’s career achievements as part of an introduction for a television interview. The same device is used later when a journalist recounts the now fiftysomething Bernstein’s later résumé to him as part of a pitch to write a biography.

The treatment of various notables who pop up in the story is similarly oblique, presenting them largely on a “if you know, you know” basis rather than identifying them. Betty Comden and Adolph Green, the team who collaborated with Bernstein on Wonderful Town, are shown delivering a snippet of song at a party and gurning wildly, leaving viewers not versed in musical theater wondering who these two loons are. Choreographer Jerome Robbins, Bernstein’s collaborator on West Side Story and Fancy Free, gets identified by name and at least gets to dance a bit (superbly, by Michael Urie), but again, if you didn’t know who he was coming in, you won’t find out here.

Similarly, there’s a bespectacled, rather geeky guy, at one point addressed as “Aaron,” who plays a duet with young Lenny and who is clearly an old friend, putting a consoling hand on Bernstein’s shoulder during a family picnic. This is in fact Aaron Copland (Brian Klugman), the distinguished composer of Fanfare for the Common Man and ballets such as Rodeo. While, as the New Yorker critic Alex Ross observed, this saves clunky exposition like “Hey, Aaron, congratulations on winning a Pulitzer Prize for Appalachian Spring!” it does leave the viewer unaware of how large Copland loomed in Bernstein’s life. He first met Copland when he was a student at Harvard, although, he wrote, “I had long adored him through his music.” Furthermore, Bernstein added, Copland became “a surrogate father to me” and “the closest thing to a composition teacher I ever had.” (This did not stop Copland from later dismissing his protégé’s compositions as “merely conductor’s music—eclectic in style and facile in inspiration.”)

The two were also occasional lovers while Bernstein was in his early 20s, but the film gives no hint if Felicia was aware of this and if it affected her feelings about Copland being at family gatherings.

With the emphasis on the personal relationships, many of the scenes depict conversations known only to the participants and so are hard to verify—although Singer has said he drew on some 1,800 letters donated to the Leonard Bernstein Collection at the Library of Congress after the composer’s death in 1990 and which were finally unsealed in 2010. Nevertheless, we try to sort out what’s score and what’s improvisation in Maestro.

Did Leonard Bernstein Go Out There an Understudy and Come Back a Star?

In the film, young Lenny, then an assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic, gets an early morning phone call in his apartment above Carnegie Hall: The regular conductor is sick, and Lenny will have to conduct the orchestra without rehearsal at that afternoon’s performance. He jubilantly slaps his lover’s butt, gets dressed, and races down to the concert hall and onto the stage. The unknown young conductor is a huge success, and his career is launched.

This is more or less what happened, although Bernstein did not go on quite as unprepared as the film suggests. As an assistant conductor, his job was to be familiar with the current season’s scores just in case he had to go on unexpectedly. And even though the orchestra wasn’t available for a rehearsal, Bernstein had time to visit the usual conductor, the flu-stricken Bruno Walter, for some coaching. “I found Mr. Walter sitting up but wrapped in blankets, and he obligingly showed me just how he did it,” he told the New York Times, which ran a story on the drama.* On the other hand, not only was Bernstein conducting without a rehearsal, it was his first time conducting the Philharmonic at all.

What About the Schnoz?

For those who haven’t been on the internet in the past six months, a kerfuffle erupted when the first publicity stills for the film showed Bradley Cooper, as Bernstein, sporting a rather large prosthetic nose, which some claimed was stereotypically Jewish and a caricature.

In fact, the nose is about the same size as Bernstein’s actual nose. The problem is: Bernstein had a different shaped face and—to editorialize a little—as a young man was actually better-looking than Cooper (although lacking the actor’s strapping physique), so his nose did not look out of proportion as it does on Cooper. Oddly, the nose does not loom as large once Cooper starts portraying the older Bernstein, possibly because the ageing makeup balances it out.

Were the Bernsteins Truly So Devoted to Each Other?

As Felicia (Carey Mulligan) and Lenny get to know each other better, it is clear they really enjoy each other’s company and are soul mates. He enthusiastically introduces her to his friends and she introduces the possibility of marriage, telling him, “I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr. … Let’s try and see what happens if you are free to do as you like, but without guilt and confession.” All she asks is that he be discreet and not embarrass her. It is when Lenny gets what Felicia calls “sloppy” in middle age, carrying on with a young man quite publicly, that she kicks him out and they separate.

The general outlines of the relationship and the bargain it entailed are accurate. In fact, it was Bernstein who proposed to Montealegre (on a trip to Costa Rica). If he was not overwhelmed by passion, it would seem he genuinely loved her, as a letter to his sister, Shirley, published in The Leonard Bernstein Letters, suggests. “How strange that you have written to me just now of Felicia!” he wrote. “Ever since I left America she has occupied my thoughts uninterruptedly, and I have come to a fabulously clear realization of what she means—and has always meant—to me. I have loved her despite all the blocks that have consistently impaired my loving-mechanism, truly and deeply from the first. Lonely on the sea, my thoughts were only of her. Other girls (and/or boys) mean nothing.”

For her part, shortly after their marriage Felicia wrote to her new husband, “You are a homosexual and may never change—you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depends on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the L.B. altar. (I happen to love you very much—this may be a disease and if it is what better cure?) … The feelings you have for me will be clearer and easier to express—our marriage is not based on passion but on tenderness and mutual respect.”

But the film leaves out some crucial moments. In fact, Montealegre was not swept off her feet but married Bernstein on the rebound. The couple met in 1947 and became engaged a few months later but then broke it off. Montealegre became romantically involved with actor Richard Hart (who in the film pays a visit to her dressing room when she is appearing on Broadway; she is clearly smitten despite being married but is devoted to Bernstein). But Hart died at the start of 1951, whereupon she gave Bernstein another chance (this earlier romance is mentioned in a later scene when Felicia and Bernstein have a big fight shortly before they separate, but we never actually see Hart and Montealegre together). The couple announced a second engagement in August 1951 and married a month later. In the interim, Bernstein had a passionate romance with an Israeli soldier, Azariah Rapoport, from 1948 to 1949.

Was Lenny Really So Relaxed About His Sexual Orientation?

In the film, Lenny appears to accept himself fully as he is, saying, “The world wants us to be only one thing and I find that deplorable.”

It does seem unlikely that a nice Jewish boy in the 1950s would have had no problem with his particular sexual preferences. It’s true that in the circles Bernstein moved in, being gay or bi was not exactly an unknown phenomenon. The American Composers League was known in the gay community as “the Homintern.” A friend of the conductor’s called Antonio de Almeida told Bernstein biographer Meryle Secrest, “They all went to bed with each other, but it was very casual. Like a Turkish bath.”

But Bernstein was sufficiently distressed by his preferences to see several psychoanalysts about it (then again, seeing a psychoanalyst was practically de rigueur for upscale Manhattanites in the ’50s). Both he and his former lover David Oppenheim (the man in the bed when Lenny gets his big break), who himself was married three times and fathered several children, were patients of a therapist named Marketa Morris, called “the Frau” in their correspondence with each other.

“You are seeing Felicia and the day she leaves you have to see a boy. The same old pattern. You can’t give up,” Morris wrote to Bernstein. The “boy” was actor Farley Granger (who starred in Hitchcock’s Rope, among many other films), who is not referred to in Maestro. A letter Granger wrote to Bernstein makes it clear he is aware of the conductor’s closeness to Montealegre, saying, “I am having Dinner with Felicia tonight. She is a great girl, and I’m sure loves you very much.” Bernstein actually asked Granger to come on the trip to Costa Rica where he popped the question to Montealegre. Fortunately, the actor seems to have had a better sense of boundaries and declined.

Bernstein also saw another analyst called Sandor Rado, who specialized in “curing” homosexual men. According to Secrest, Bernstein told a friend that “where sex was concerned, he had always been very adaptable but he had decided that homosexuality was a curse. He was so tense and emphatic about it. He felt marriage had saved him from a homosexual lifestyle.”

In fact, it’s useful to compare the Bernstein-Montealegre marriage to the marriage of Oscar Wilde and his wife, Constance, who knew of her brilliant husband’s dalliances with young men and was devoted to him nevertheless, while he in turn, like Bernstein, made her and their children the center of his emotional world.

Who Was Bernstein’s True Love?

Beyond the initial debut scene, Maestro barely mentions Felicia’s most significant rival and the true love of Bernstein’s life—not one man but approximately 90, the New York Philharmonic (all male until 1966). Bernstein became music director of the orchestra in 1958, remaining in the post until 1969 and leading more concerts with it than any previous conductor. Even after he left, he was given the lifetime title of laureate conductor and made frequent guest appearances with the NYP, which played on more than half of his 400-plus recordings. When Bernstein announced he wouldn’t be extending his contract, he said, “I shall always regard the Philharmonic as ‘my’ orchestra.”

And his affection was reciprocated. According to a 2023 article in the New York Times, following the announcement that Gustavo Dudamel will succeed current conductor Jaap van Zweden: “There has been a palpable sense that the Philharmonic essentially wants a repeat of the Bernstein of the 1960s, when he was not just one of America’s best known musicians, but also one of its best known figures, period. … The Philharmonic quickly came to perceive his as the true glory days of the nation’s oldest orchestra.”

Correction, Dec. 23, 2023: This piece originally misidentified the musical for which the ballet Fancy Free provided the basis. It was On the Town, not Wonderful Town.

Correction, Jan. 2, 2024: This piece originally misstated that the story about Bernstein’s first Philharmonic concert, at Carnegie Hall, appeared on the front page of the New York Times.

Update, Jan. 4, 2024: This post was updated to more accurately characterize Bernstein’s relationship with Copland.