They say you need to return to a great artist at different times in your life, to see how the work will resonate with your own changing experience.

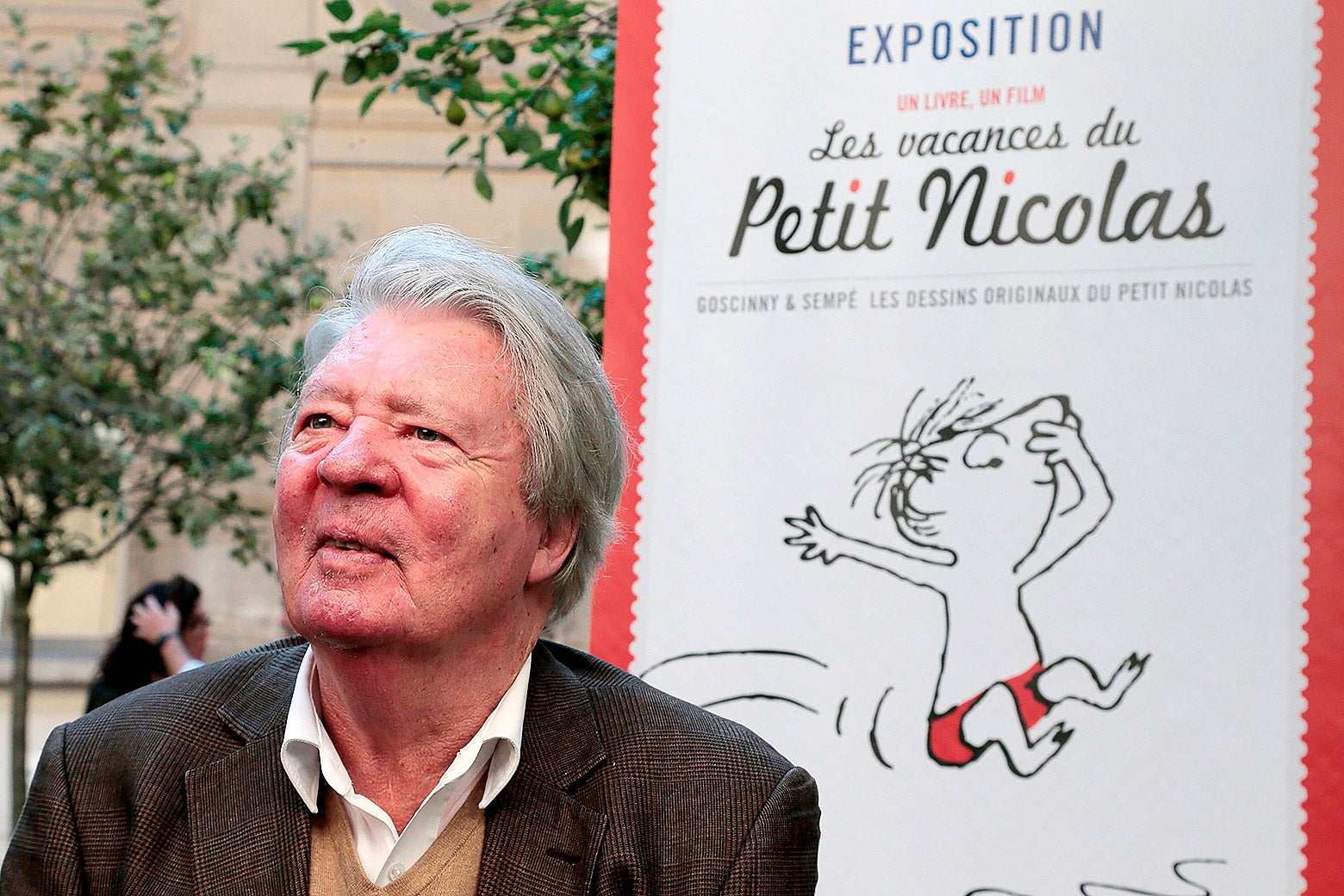

So it was for me with Jean-Jacques Sempé, the French cartoonist who died Thursday at the age of 89, through whose whimsical pen the joys of children, the rites of adults, and the profound thrills of riding a bicycle came to life.

His ink cartoons were often set in a mythical mid-century Paris or millennial New York, but their appeal was universal. They showed sparely drawn figures in the midst of timeless pleasures and trials: classroom exams, country picnics, traffic jams, concerts, fancy parties, marital arguments, daydreams, errands, and chores. In his hands, the mundane stuff of life—enlivened with visual gags, loving detail, or Looney Toons-style silliness—became by turns philosophical, melancholy, and laugh-out-loud funny.

Over a seven-decade career, Sempé drew thousands of cartoons for French newspapers and magazines, and released dozens of books. To Americans he is probably best known for the watercolor covers he painted for the New Yorker over the past few decades. But I first encountered him in the best-selling series of children’s books he produced with the writer René Goscinny, beginning in 1960, “Little Nicolas.”

In the stories, which my dad read to me as a kid, Nicolas and his band manage to turn just about any routine activity, such as a class photo or a soccer game, into a fracas. As in “Calvin and Hobbes,” these quarrelsome brats often dispense some wisdom along the way. “When you play all alone, you don’t have any fun,” Nicolas muses, “and when you’re not alone, the others create so many arguments.”

Compared to François Truffaut’s films about childhood, which dealt with subjects like poverty and abuse, the drama of these vignettes is the opposite: Here, it’s the children who make life difficult for the adults. A story about playing cowboys ends with Nicolas’s dad tied to a tree all afternoon as the gang loses interest and wanders off to do other things. My dad, meanwhile, would laugh so hard he couldn’t finish the chapters.

For most of his career, Sempé drew light-hearted cartoons for French newspapers and magazines. A man begins a speech with, “I will be brief—“ as a chandelier plummets towards his head. Two women have tea in a room covered in paintings of household tools while, in the garden, a man paints a rake. A man fishing from a bridge over the railroad tracks tells his children, “No! No use asking, you broke my glasses and you won’t be going swimming.”

As opposed to the group brawls of “Little Nicolas,” many of Sempe’s adults are solitary city-dwellers. Two lit apartments on a darkened Parisian street. A woman looking out her window at the parties in the building across the way. Often, they buffer their isolation with a childlike joie-de-vivre. A man with a briefcase kicks up autumn leaves in the park. A man in a smoggy gray city is transfixed by a colorful still life painting in a window. A man on the beach tips his cap to the sea.

There were many recurring motifs in Sempé’s work—cats, cars, saxophones, children—but none that turned dead-eyed commuters into serene nonconformists quite like the bicycle. Bikes are everywhere in Sempé’s work. Sometimes they are used to narrative effect, like when he shows the evolution of commuting from a single house, from bicycle to car and back again. But often they are just there to be ridden, in hundreds, if not thousands, of sketches of smiling people on bikes having a good time, presumably shirking their boring jobs to go for a ride. The Prime Minister of France shared one such image to commemorate his death; the mayor of Paris recently used another one as her Christmas card.

Most of us can recognize the blues of adulthood in Sempé’s drawings. But a smaller group of us may know, also, the joy of the bicycle—the magic of the machine that seems to offer companionship in solitude, inspiration in boredom, and even, in low moments, a fleeting kind of grace.

A few years before he died, Sempé drew a New Yorker cover that showed a group of cyclists taking a photo together on a country road. It reminded me of “Little Nicolas,” of a friend group where everyone’s role is as fixed a part of the whole as the components of a bicycle. But even for Sempé, getting the gang together proved elusive. In 2019, he was asked about this illustration:

It’s always been one of my dreams—to have a group of friends who go for bike rides in the country every Sunday morning. In real life, it never happened. I kept trying to organize it but everyone was always too busy to slow down for it … We’d get a bit of exercise, build some muscle and also spend some time together. We’d take our bikes on the train and get to the small country roads that run along the fields. It’s quiet and smells good and it’s totally out of fashion. Sometimes one of us would know a good country restaurant, but then it would turn out that it was closed. I keep thinking back on those outings—it’s one of the things I really wish I had done.

Last year, hoping to buy one of Sempé’s drawings, I stopped into the Galerie Martine Gossieaux, the Parisian gallery run by his wife and agent. I was disappointed: Most of the work on sale was priced in the low five figures. Chastened and embarrassed, I pretended to continue to browse, before I worked up the nerve to ask if there was anything cheaper … much cheaper.

And there was. For 20 bucks I took home a poster for an old exhibition that showed one of Sempé’s most famous New York illustrations: a lone biker cruising over the Brooklyn Bridge as traffic stands still below him. I once biked the same path to get to high school. The poster seemed to contain my entire evolution as a Sempé character, the journey from my childhood crew to life as another working adult measuring out moments of bliss in pedal strokes.

For many years, there was a Sempé drawing that belonged to all of us in Midtown Manhattan. Commissioned in 1985 by the owners of a bike shop, Sempé sketched a pair of lovers on a bicycle on a brick wall on 47th Street and 9th Avenue. Last I checked, the mural was still there, though the paint was chipping badly. The shop had long since closed and been replaced by a Kiehl’s. There goes the neighborhood, Sempé might have said. But then again, the amorous bicycle couple, faces peeling down to the brick, above a shop that sold skin cream—the whole scene had almost become one of his cartoons.