Untangling the Running Shoe Knot: How to choose the right shoe

This post is about a key component of your running health: footwear. With all the miles you have logged already, and the many more to come, you’ll need to make sure you’re wearing the right running shoe for you. Some of you have already figured that out and have been wearing a successful shoe for years. Others are still searching for that perfect shoe. If you’re in that group, read on for some tips and information to help you navigate the process.

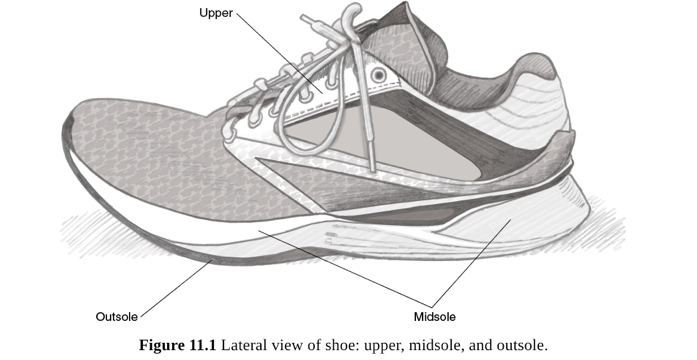

Let’s start with shoe anatomy. The running shoe is a higher-tech piece of equipment than you may realize, with myriad gadgets and parts, but the basic structure you need to know is pictured here:

From Puleo and Milroy, Running Anatomy

The upper is the part of the shoe that hugs your foot, the midsole comprises the shoe cushioning, and the outsole is the part of the shoe that makes ground contact. These components can be manipulated to fit the needs of different runners. Which brings me to the next part of my discussion: shoe types.

When you shop for a shoe in a store or search on-line you’ll see references to different shoe types; for example, neutral shoes, stability shoes, or motion control shoes. Below is a brief definition of each type:

Neutral: Shoes with even cushioning throughout the midsole.

Stability: Shoes with a higher-density foam in the middle part of the midsole. This is meant to limit the amount of midfoot collapse, and can be helpful for people who pronate (have flatter arches). The higher-density foam is firmer, making stability shoes feel less cushioned than their neutral counterparts.

Motion Control: This type of shoe also has a higher-density foam in the middle part of the midsole, and has a plastic plug beneath the heel of the shoe to prevent movement of the back of the foot (termed rearfoot eversion). This is the most stable, least-cushioned type of shoe.

When shoe shopping, you may also encounter the following extreme shoe types: minimalist shoes and maximalist shoes.

Minimalist shoes are shoes with very little cushioning or no cushioning at all; examples are New Balance Minimus, Merrell Barefoot, and Vibram FiveFingers. For distance running, only runners who are very used to running in this type of shoe and have been doing so for many years should use these shoes. They require a great deal of foot, ankle and calf strength to run in them without getting injured.

Maximalist shoes are shoes with a greater amount of midsole cushioning than the typical running shoe; examples are Hoka One or Altra shoes. Many runners find this type of shoe to be helpful on longer runs or recovery runs because of the added cushioning.

A few other things to pay attention to regarding running shoes:

Stack Height and Heel-Toe Differential (or “drop”): Stack height is the total amount of shoe between your foot and the ground, and is measured in millimeters (mm). The Heel-Toe drop is the difference between the stack height beneath your heel, and the stack height beneath the front part of your foot, termed the forefoot. Traditional running shoes have a heel-toe differential of 12-14 mm and stack heights of 20-30 mm.

Recently, many shoe companies have decreased the heel-toe drop to the 8-10 mm range, and some models go as low as 0-4 mm difference. This is important because if you are accustomed to running in a shoe with a larger heel-toe drop and you switch to a shoe with a lower heel-toe drop, this could be a set-up for injury. I have had many runners come in to my clinic with foot and ankle issues such as Achilles tendinitis or plantar fasciitis because they did not realize they were running in a shoe with a lower heel-toe drop than they were used to. So be careful when switching shoe models, or when buying an updated model of your current shoe.

Shoe mileage: Unfortunately, even the most beloved of running shoes have a finite life, and continuing to run in a worn pair of shoes can also put you at risk for injury. Make sure you are keeping track of how many miles you have on your shoes, and be sure to change to a new pair every 300 to 500 miles.

So, which shoes should you buy?

One of the best discussions of footwear I have read is an article by Nigg et al. in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (2015) titled “Running shoes and running injuries: mythbusting and a proposal for two new paradigms, ‘preferred movement path’ and ‘comfort filter.’ This article summarizes the literature on the association between running injuries and footwear, and points out how variable this literature actually is. The authors conclude that shoe comfort is the most important factor to consider when choosing a running shoe for the following reasons:

1. Different runners consider different shoe features to be comfortable (for example, some like more arch support, or more cushioning, and others don’t).

2. More comfortable shoes are consistently associated with a lower frequency of running injuries (the data is less consistent for other factors that have been studied in association with running injuries).

3. Running in shoes that are comfortable is less work for the runner (i.e. has been associated with less oxygen consumption during running).

Given this, I always advise runners to try out different shoes and to choose the ones that feel the most comfortable. Many specialty running stores will let you do this, and will even allow you to return a shoe if you buy it, bring it home, do a few runs and determine it’s not the right shoe for you. Choosing the right shoe can be a daunting and time-consuming process, but I hope after reading this post you feel more running shoe savvy. After all, keeping your feet happy will help keep you healthy and out on the roads.