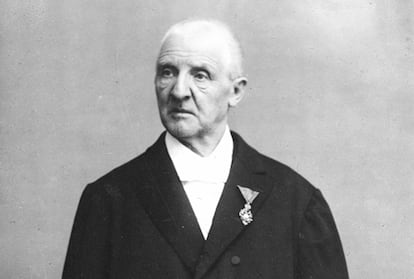

Anton Bruckner on his 200th birthday: A late bloomer and misunderstood genius who was the greatest symphonist after Beethoven

The celebration of the Austrian composer includes biographies and two disappointing symphony cycles by Christian Thielemann (Sony) and Andris Nelsons (DG)

Anton Bruckner (Ansfelden, 1824–Vienna, 1896) was the greatest symphonist after Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt boldly states in his foreword to Felix Diergarten’s biography Anton Bruckner. Ein Leben mit Musik, which Bärenreiter just published to commemorate the bicentennial of the composer’s birth. In making that claim, the 96-year-old dean of conductors —according to Bachtrack statistics, he conducted the tenth most concerts in 2023— does not detract from the achievements of Brahms, Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Shostakovich, Sibelius and Nielsen. But as he points out, “none of them could capture the inner grandeur of the symphony as convincingly as Bruckner.”

For Blomstedt, who completed an excellent integral recording in 2012 with the Leipzig Gewandhaus, these symphonies represent a longing for the eternal. But he does not consider them religious: “Bruckner was looking for a concert hall for the whole world.” Blomstedt believes that no matter how devout and Catholic the Austrian composer may have been, “music was his profession of faith.” He also speaks of Bruckner’s colossal and demanding works that “are characterized by great intellect, but which also manage to express themselves briefly and simply when necessary.”

For nearly seven decades, he has been instilling in audiences the patience that these gigantic and fascinating compositions require. And he considers it an achievement that, after conducting the lengthy and brainy Fifth Symphony in Seoul, he received a red rose and a card with four words, “Bruckner is too short.” That was the overall impression at the recent New Year’s Concert with a documentary at intermission peppered with short samples of sound. And it was also true of an irrelevant five-minute quadrille, in its second part, an occasion piece that Bruckner wrote in 1854 to entertain the Linz collegiate judge Georg Ruckensteiner, and more specifically his daughter Marie, who aspired to an appointment as organist.

We read the latter in August Göllerich and Max Auer’s monumental biography in German, published (in 9 volumes!) between 1922 and 1937. It’s an admirable work, but it also includes made-up stories and falsifications that adorned Bruckner’s unattractive life with tasty anecdotes about frustrated love affairs and self-esteem problems. It also fabricated an insecure and neurotic artistic personality in keeping with his symphonies, which Bruckner revised again and again. In 1972, Karl Grebe began to correct that distorted image in his careful documentary work, where, for the first time, Bruckner’s music was no longer presented as a symbolic reflection of his life, his beliefs and his obsessions.

In his 2004 biography, Constantin Floros begins from that old-fashioned conviction that “his music is an expression of his spirituality and inner world” (p. 175). Far from composing an account of life and work, the 94-year-old Greek-German musicologist traces an intricate psycho-biographical profile in which he erroneously links various facets of Bruckner’s character with the stylistic and structural aspects of his compositions.

On the other hand, in the new book in German, which features a foreword by Blomstedt, Diergarten succeeds in composing the most truthful and up-to-date portrait of the Ansfelden-born composer. The tome captures a simple man of rural origin who was also richly cultivated, an eccentric and submissive being, who plotted an impressive ascent from the rural school and the village masses, in Windhaag bei Freistadt, to the university and the great symphonies in Vienna. The book portrays a musician who was modest in public and superb in private. It tells of the misunderstood genius who found success late, who did not compose his first symphony until he was almost forty years old, an age that Mozart, Schubert and Mendelssohn never reached. Finally, it shows that he was a religious Catholic who nevertheless wanted to go down in history as a symphonist.

Bruckner never endowed his symphonies with religious content. Even the famous dedication of the unfinished Ninth, “to the beloved God,” is not found in any of the composer’s documents but rather in several contradictory testimonies of his doctor, Dr. Richard Heller. And, among Bruckner’s dedications, it is striking that he dedicated the Fifth to the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s Minister of Education, Karl von Stremayr, a member of the liberal party and supporter of the separation of church and state. Diergarten immerses us in a fast-paced narration of each work and its context, as he does with the Eighth, entitled The Great Theater of the World, with technical explanations that are as interesting to the connoisseur as they are accessible for the amateur. The booklet is little more than two hundred pages and reading it is a continuous pleasure.

Returning to Floros’s biography, the last two chapters are perhaps his most successful. In the penultimate, he reviews the Austrian’s most significant conductors, especially important since Bruckner’s symphonies require specialized conductors. It should be noted that the Brucknerian catalog starts in 1863 with a study symphony (No. 00) and includes a symphony discarded between the First and Second (No. 0); there are also several versions of some symphonies: two of the First, Second and Eighth and three of the Third and Fourth.

Floros highlights three great maestros who died between 1987 and 2002. He emphasizes Eugen Jochum’s ability to attract the public to Bruckner’s symphonies with agile, fluid versions, full of expectation. He underscores Sergiu Celibidache’s intensity with slower tempos and the deliberate renunciation of expressive liberties. However, his favorite was Günter Wand, whose interpretations showcased Bruckner’s major advances by developing the symphony not thematically, like Viennese classicism, but architecturally: He did so “through a clear juxtaposition of sound blocks, tempi and rhythms that do not merge with each other, but are placed side by side like bricks” (p. 255).

Perhaps Floros could have added Herbert von Karajan and highlighted other great Brucknerians such as Bernard Haitink, Daniel Barenboim and the aforementioned Blomstedt. But the composer’s bicentennial coincided with the release of two complete symphonies on disc by Christian Thielemann and the Vienna Philharmonic, on Sony Classical, and by Andris Nelsons and the Leipzig Gewanhaus, on Deutsche Grammophon. Both are disappointing for different reasons.

Between 2019 and 2022, Thielemann recorded the cycle of 11 symphonies, including the studio and discarded symphonies (the so-called No. 00 and No. 0). It’s a version that exalts the sonorous glamour of the Viennese orchestra—which premiered several of Bruckner’s symphonies—but it sacrifices the music’s depth. This is not a problem of agility or fluidity, of slow or fast tempos, but simply an issue of interpretations blinded by timbral hedonism and a lack of emotion. On the other hand, Nelsons began his cycle in 2016 and ended it five years later, albeit without the studio symphony. The Leipzig orchestra also offers sonic excellence along with a solid tradition, as it premiered the Seventh symphony, although the result is contemplative and superficial.

Neither cycle has the excitement, depth and jubilation heard in Jochum and Wand. But, in Bruckner’s bicentennial year, the most interesting cycle is being released by the Capriccio label under the direction of Markus Poschner. By the end of 2024, the project will include all 19 versions of Bruckner’s eleven symphonies. The ones released so far, the Bruckner Linz Orchestra and the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, have surpassed the recordings from the aforementioned Sony and DG cycles in their freshness and depth.

Floros dedicates the final chapter of his biography to vindicating Bruckner’s modernity. He does not hesitate to use the same description as Schönberg did with Brahms: progressive. That is the same concept that will be emphasized in the main exhibition dedicated to Bruckner this year: Anton Bruckner: The Pious Revolutionary, curated by Thomas Leibnitz and Andrea Harrandt. The exhibit will open on April 1 at the Austrian National Library and will be accompanied by the book launch of another monograph featuring contributions from leading specialists on the Austrian composer. This will serve to continue correcting his battered historical image and promote the experience of his symphonies. Then as now, Bruckner needs believers and officiants to celebrate his bicentennial.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition