Editorials

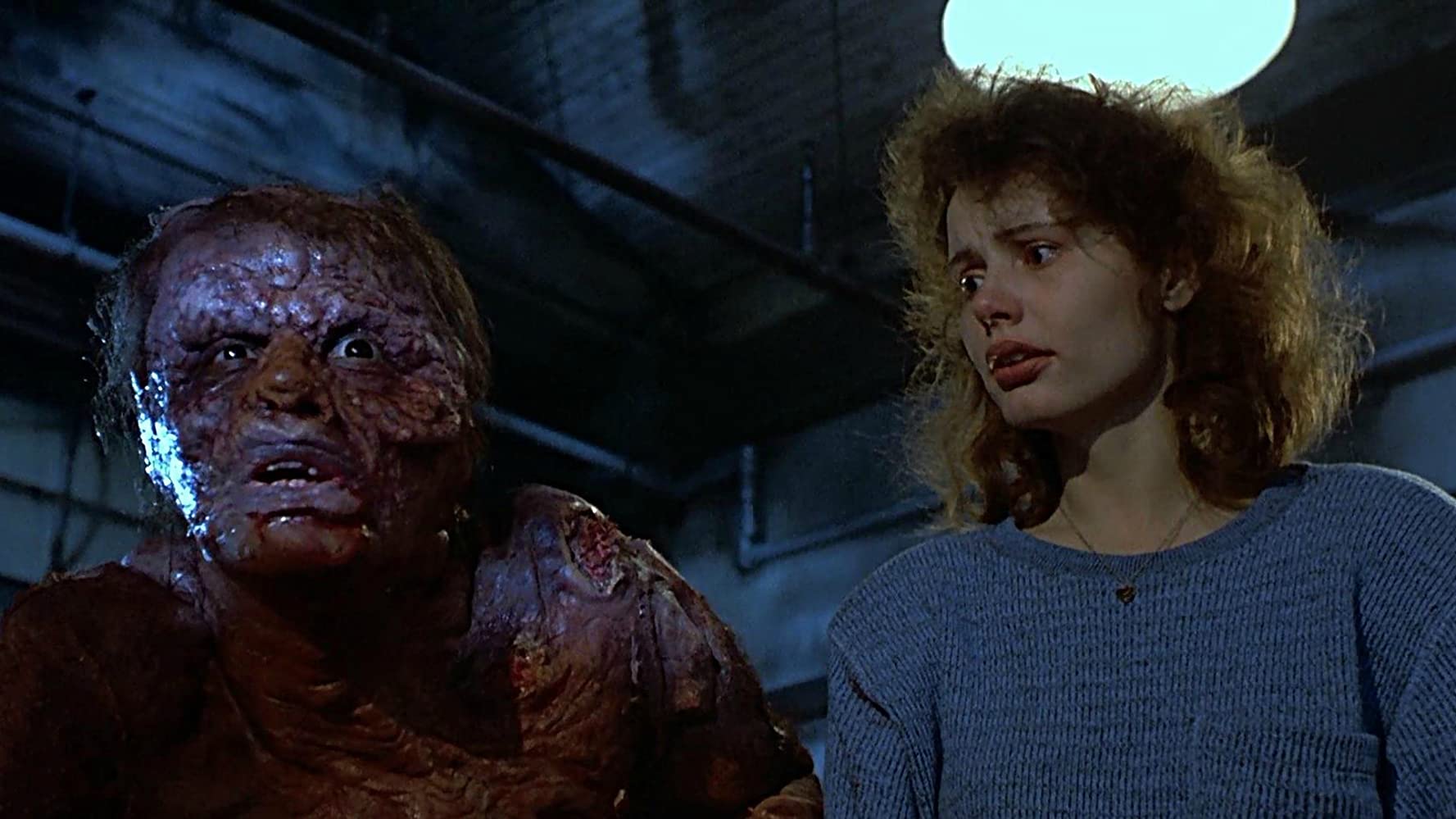

David Cronenberg’s ‘The Fly’ Continues to Make a Strong Pro-Remake Argument [Revenge of the Remakes]

David Cronenberg‘s The Fly (1986) upholds a storied tradition of 80s remakes reinventing classic horrors through emblematic practical effects. John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) and Chuck Russell’s The Blob (1988) both embrace the spectacle of SFX advancement to build a better goopy mass or parasitic entity. Kurt Neumann‘s 1958 iteration of The Fly, co-starring Vincent Price, attempted an insectoid transformation before any of the tricks and practices that’d win Chris Walas an Academy Award for his “Brundlefly” monstrosity. There’s an old-school Hollywood allure to Ben Nye‘s 20-pound fly head in Keumann’s science-fiction mystery. Still, everyone involved with the remake saw an opportunity to pay homage and evolve The Fly into something eternally horrific. The ultimate reasoning for remake motivations: new technology after decades pass.

Any aughts-era bias against horror remakes is peculiar when you consider how the 80s were just as predominantly centered on remakes, albeit pulling from earlier source generations. There’s no difference between Platinum Dunes plucking Freddy Krueger and Jason Voorhees into the next millennium when studios in the 80s set their sights on retelling 50s and 60s black-and-white terrors. Where does a person with their Brundlefly tattoo get off outcrying about 2000s teens supporting their update of Friday the 13th? Remake gatekeepers are the silliest complainers, made evident by Cronenberg’s buzzworthy all-timer that broke the Oscar’s anti-horror “bias.” Walas’ reinvention of Nye’s creature is one of the genre’s glistening pro-remake arguments, not to mention the entire production’s vastly altered narrative.

The Approach

Comparisons between Kurt Neumann’s and David Cronenberg’s The Fly are nonexistent. George Langelaan‘s short literature serves as the starting point for both — executions range from original writer James Clavell‘s research journal detective debacle to Cronenberg’s shared screenplay credit churning out a Kafkaesque metamorphosis with creature-feature structures. André Delambre (David Hedison) is a family man reminiscent of 50s Pleasantville stereotypes who protects those around him from his instant swapping of fly head and hand — most of the bygone film revolves around his wife Hélène (Patricia Owens) trying to locate a white-headed fly as evidence. There’s little horror outside the now-infamous “Help me!” squeals from a human-headed fly (achieved through photographic projection) before a spider (puppet) feasts on its insides.

Cronenberg’s reinvention — starting with the pages of Charles Edward Pogue‘s first draft that Cronenberg himself demanded be honored through Pogue’s co-writer credit — is vastly more beastly. Jeff Goldblum plays the brilliant Seth Brundle, working out of a converted Toronto warehouse apartment as a freelance inventor. He persuades journalist Veronica “Ronnie” Quaife (Geena Davis) with the promise of a revolutionary device to vanquish his motion sickness. Brundle reveals what he dubs “Telepods,” two teleportation chambers (modeled after Ducati cylinders and cylinder-heads). Veronica flirtatiously removes one of her knee-high stockings so Brundle can demonstrate — it later works on a baboon. With trials moving swiftly forward, as rapidly as his relationship with Veronica, Brundle indulges an impulse decision fueled by jealousy and champagne to accelerate human tests by unknowingly hopping inside with a common house pest.

The Fly remake rebirths with all of Cronenberg’s goopy-sexual, body-horror signatures that couldn’t be any further from the sitcom wholesomeness of Neumann’s curiosity. André protects Hélène from his deformation except for one tussle under the hydraulic press to show the fly’s psychological takeover — Seth becomes a fornication machine energized by sugary snacks who allows his spliced genetics to define his personality. Physical variations are noticeable given how André emerges from his “Disintegrator Integrator” device looking like Baxter Stockman from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (evident reverse influence) while Seth indulges Cronenberg’s pustulating, finger-nail pulling, flesh-shedding transformation over time. The mental aspects unlock Jeff Goldblum’s distancing from David Hedison’s valiant patriarch — Seth is unstable, feral, and sees his new DNA as transcendence. There are no parallels to draw.

Does It Work?

I hope you’ll allow a brief repetition of my justifications throughout this column’s previous analysis of The Blob — developments in the profession of special effects necessitate remakes. Perhaps even tied to budget allowances. The Fly is a remarkable milestone for 50s cinematic achievements between André’s weighty prosthetics and Whitehead’s demise. However, Chris Walas’ progression of sticky suits, wriggly animatronics, and makeup oversight are still heralded by even today’s SFX standards. The multiple stages of Jeff Goldblum’s “Brundlefly” are complete with decomposition, peel-off appendages, and an acidic vomit that melts victim’s… anything. Walas’ accomplishments aren’t a slight against Ben Nye’s wizardry at the time, merely another film with the same ambitions of pushing practical effects boundaries as far as inhumanly possible. “Brundlefly” should be the only retort to questions about why remakes are a continued tradition.

From a visionary perspective, David Cronenberg proves another stellar remake point — filmmakers with distinct styles help individualize remakes. Cronenberg’s secretion-slimy, disgustingly decadent portrayal of mad scientist madness is almost like Frankenstein where Goldblum plays both doctor and monster. It’s as Cronenberg as Cronenberg World from Rick And Morty, down to multiple sex breaks that feature Goldbum’s gyrating rump or breathing perversions of imagination that slither from plasma pools. It’s a remake that distances itself like Robert Muldoon driving away from the T-Rex in Jurassic Park. Even if you’ve seen 1958’s The Fly, there’s no predictability beyond introducing a fly-man hybrid at some benchmark. Geena Davis is the anti-Hélène as her romance morphs into something dangerously ugly, saddled with a pregnancy she demands to terminate, as she aims a shotgun at the heartbreaking abomination that once brought so much love and joy knowing what must be done.

The one questionable diversion in Cronenberg’s The Fly remake is Stathis Borans, played by John Getz. He’s Veronica’s confidant — and stalker ex-boyfriend who refuses to return her extra key? Stathis is an A+ creeper who also worries about Veronica, whether that’s him already being in her apartment when she returns from Seth’s or at work, where he’s her publication boss. Cronenberg reportedly fused two characters from Charles Edward Pogue’s draft — a best friend character Harry Chandler, and greedy corporate villain type Phillip DeWitt — into this union of friend and foe who has his moments but also unpleasant encounters. The ex who never leaves; the acquaintance who genuinely fears for your life. In the context of a practical effects showcase? Some might glance over Stathis’ odd traits. Others won’t.

The Result

I’ll let Chris Walas’ golden statue lead my argument — The Fly remake belongs up there with The Blob, The Thing, and many other 80s displays of championship practical effects. Brundlefly’s many iterations all execute their desired reactions from cringes when Veronica attempts to “shave” thick fly hairs betwixt split wounds to the final abhorrent fusion of insect-man and machine. David Cronenberg’s taste for alluring visual provocation has taken many forms, few as iconic as Brundlefly. What do you want me to say that hasn’t already been described in precise detail by horror scholars for decades? The result of Brundlefly is everything from astounding to ghoulish to vital among seventy-thousand other descriptors.

Jeff Goldblum’s performance embraces the Goldblum we know — you don’t hire Goldblum to play your character; said character becomes Jeff Goldblum. In the case of Seth Brundle, the impish mannerisms of a thinker who traded social skills for further braininess become eccentric comforts. Goldblum’s extreme gesticulation from his dart-all-day eyes to the outreach and grasp-at-air of a hand all delight, but his ability to monologue about complex science fiction terminology without blinking sells Seth Brundle. There’s a precise moment where Goldblum goes out-of-body as Seth preaches his teleportation aura as this new religion, something about the pierce past “new flesh” and baptism of plasmatic ponds, representing divine Goldblum theatrics. I can only imagine producer Mel Brooks chuckling to himself after watching the take, knowing the madness capable between Cronenberg and Goldblum. Look no further than Seth’s tipsy confession to his baboon assistant — complete with an apology for inside-outing his brother.

Cronenberg never besmirches Kurt Neumann nor his original film — there are loving odes littered throughout bugification. Veronica asks Seth earlier into their relationship why he’s always wearing the same suit-jacket outfit, a possible poke at André since Neumann’s protagonist always dons the same dapper scientist getup day after day in flashbacks (explained away by Seth as Einstein’s theory of expending energy elsewhere). There isn’t a battle for supremacy between films. They exist as footnotes in horror history that encapsulate the creativity of their times, both experimental in theme and nature. The ’50s get their abstract whodunit with an added Vincent Price bonus — gotta love “fly vision” and the over-dramatization that is André confronting his molecular fate — while the ’80s produce another testament to the longevity of practical models and molds filled with grotesque nightmare figments.

The Lesson

Check to make sure your favorite nostalgia title isn’t a remake before you start criticizing teenagers for Friday the 13th (2009) being their entry to a staple horror franchise. Opposing remake arguments often whine about how remakes are devoid of originality, yet David Cronenberg splices together one of the most noticeably unique 80s horror standouts with The Fly. There’s no copycat desire or recycled highlights. Not even when it comes to Kurt Neumann’s finale, arguably the shockwave moment that fans would lose their proverbial shit over when spider devours man before a moral-justice discussion about killing out of mercy. Cronenberg doesn’t glide behind Neumann’s jetstream for a single second, adaptation or not. The Fly is anything but artistically bankrupt, and I sure as hell don’t remember any larva abortion sequence in black-and-white.

So what did we learn?

- Don’t watch The Fly during a meal unless it’s the 1958 version.

- 1980s practical effects are a gift that forever gives — Brundlefly is no exception.

- Jeff Goldblum and David Cronenberg are the epitome of singular talents and showcase how irreplicable personalities can drive remakes down their own paths.

- I have another new favorite 80s horror film to add to the list.

Cronenberg and Kurt Neumann elope as one of the oddest couples in original/remake canon. The 1958 version loses me in parts as tension and thrills revolve around a remarkably unfazed boy somehow cucumber-cool about his family’s disintegration, just skipping around with a bug net. There are some hilarious lines delivered by child actor Charles Herbert when the tiny rascal drops “women, right?” jokes like he’s a 90s stand-up comic, but it’s a largely unbalanced fly hunt otherwise. Cronenberg’s 80s respawn has its share of questionable plot tactics — again, Stathis’ hero moment is an interesting choice for a possessive ex — but those pustulating, yucky-terrific effects are the antidote that cures all conceptual iffiness. I’m not sure how either exists, yet horror cinema is a better place with both species.

In Revenge of the Remakes, columnist Matt Donato takes us on a journey through the world of horror remakes. We all complain about Hollywood’s lack of originality whenever studios announce new remakes, reboots, and reimaginings, but the reality? Far more positive examples of refurbished classics and updated legacies exist than you’re willing to remember (or admit). The good, the bad, the unnecessary – Matt’s recounting them all.

Editorials

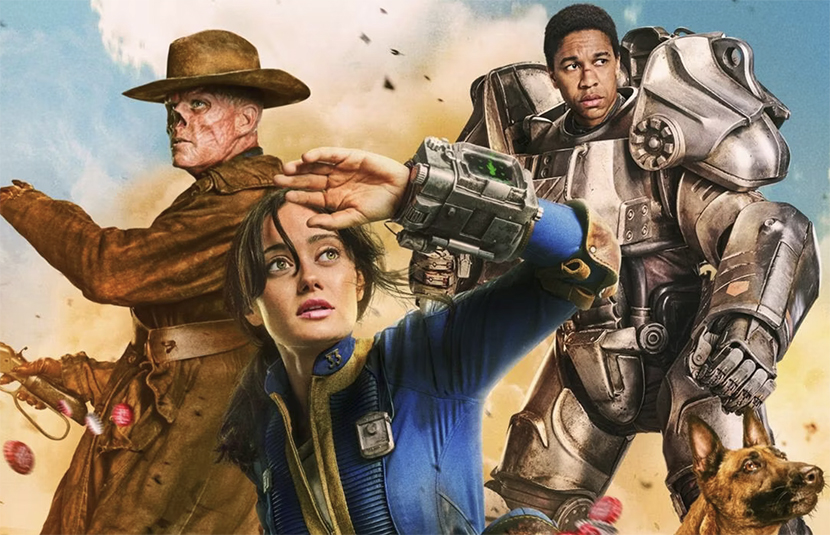

Six Post-Apocalyptic Thrillers to Watch While You Wait for “Fallout” Season 2

Despite ancient humans having already overcome several potential doomsday scenarios in real life, post-apocalyptic fiction used to be relatively rare until the invention of the atomic bomb convinced us that the end of the world could be just around the proverbial corner.

Since then, we’ve seen many different stories about the collapse of civilization and the strange societies that might emerge from the rubble, but I’d argue that one of the most interesting of these apocalyptic visions is the post-nuclear America of the iconic Fallout games. A witty satire of American jingoism and cold war shenanigans, it’s honestly baffling that it so long for us to finally see a live-action adaptation of this memorable setting.

Thankfully, Graham Wagner and Geneva Robertson-Dworet’s Fallout TV show isn’t just a great adaptation – it’s also an incredibly fun standalone story that makes the most of its post-apocalyptic worldbuilding. And since fans are going to have to wait a while to see the much-anticipated second season, we’ve decided to come up with a list highlighting six post-apocalyptic thrillers to watch if you’re still craving more Fallout!

As usual, don’t forget to comment below with your own apocalyptic favorites if you think we missed a particularly fun one. And while it’s not on the list, I’d also like to give a shout-out to The Hughes Brothers’ underrated post-apocalyptic action flick The Book of Eli – which I recently covered in its own article.

With that out of the way, onto the list…

6. The Divide (2011)

Xavier Gens may be best known for his memorable contribution to the New French Extremity movement – with the eerily prescient Frontière(s) – but the filmmaker is also responsible for a handful of underrated thrillers that flew under the radar despite being legitimately solid films. One of the most interesting of these flicks is 2011’s The Divide, a single-location exercise in claustrophobic tension.

Telling the story of a group of New Yorkers who find themselves trapped in a bomb shelter after a surprise nuclear attack, this dark thriller is more interested in the ensuing social chaos than effects-heavy physical destruction. And while critics at the time were horrified by the bleak story and cynical characters, I think this mean streak is precisely what makes The Divide worth watching.

5. The Day After (1983)

One of the highest-rated TV films of all time, ABC’s The Day After is one of the scariest movies ever made despite being more of a speculative docu-drama than an actual genre flick. Following an ensemble of families, doctors and scientists as they deal with the horrific aftermath of all-out nuclear war, this radioactive cautionary tale was vital in convincing real-world politicians to review their policies about nuclear deterrence.

In fact, the film is even credited with scaring President Ronald Reagan into changing his mind about expanding the United States’ nuclear arsenal, with this new stance eventually leading to a treaty with the Soviet Union. With a story this powerful, I think it’s safe to say that The Day After is a must watch for Fallout fans interested in the more down-to-earth elements of the apocalypse.

4. The Postman (1997)

If I had a nickel for each unfairly maligned post-apocalyptic epic starring Kevin Costner that was released in the 90s, I’d have two nickels – which isn’t a lot, but it’s weird that it happened twice. And while Waterworld has since seen a resurgence in popularity with fans defending it as a bizarrely expensive B-movie, I haven’t seen a lot of discussion surrounding 1997’s more serious vision of a fallen America, The Postman.

Following Costner (who also directed the flick) as a post-apocalyptic nomad who begins to rebuild America by pretending to be a member of the newly reformed postal service, this David Brin adaptation is consistently fascinating – especially if you view the story as a cynical fairy-tale, which was Costner’s original intention.

And while the flick suffers from some goofy dialogue and a bloated runtime, it makes up for this by having directly inspired Hideo Kojima’s Death Stranding.

3. Turbo Kid (2015)

Turbo Kid may have been billed as an indie Mad Max with bicycles instead of cars, but François Simard, Anouk Whissell and Yoann-Karl Whissell’s comedic throwback to the post-apocalyptic future of 1997 is much more than meets the eye. From quirky characters to madly creative designs, the flick rises above nostalgia bait by being a legitimately fun time even if you don’t get the copious amounts of ’80s and ’90s references.

And despite the horror-inspired ultraviolence that colors the frequent action scenes as we follow a young comic-book fan deluding himself into thinking that he’s a superhero, it’s the childlike sense of wonder that really makes this a treat for cinephiles. It’s just a shame that we’re still waiting on the sequel that was announced back in 2016…

2. Six-String Samurai (1998)

A lo-fi homage to spaghetti westerns and classic samurai films – not to mention the golden age of rock ‘n roll – Six-String Samurai is a must-watch for those who appreciate weird cinema. While I’ve already written about the madly creative vibes that make this such an entertaining flick, I think it’s worth repeating just in case some of you have yet to give this musical fever dream a try.

And appropriately enough for this list, the film was also a source of inspiration for the 3D Fallout games – especially Obsidian’s fan favorite New Vegas. The game even includes a New Vegas Samurai achievement (unlocked by killing enemies with a katana) with a vault-boy illustration modeled after the film’s rendition of Buddy Holly.

1. A Boy and His Dog (1975)

The grisly post-apocalyptic comedy that inspired the original Fallout games, L.Q. Jones’ adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s novella is just as shocking today as it was back in ’75. Telling the story of a teenage scavenger who travels the wastelands of 2024 America alongside his telepathic canine companion, A Boy and His Dog feels like a Heavy Metal comic brought to life.

While the film’s rampant misogyny and brutal violence make it tough to revisit under modern sensibilities, it’s still a landmark in post-apocalyptic cinema and one hell of a memorable ride. Not only that, but the flick also inspired the creation of Fallout’s most beloved NPC, the ever-loyal Dogmeat.

You must be logged in to post a comment.