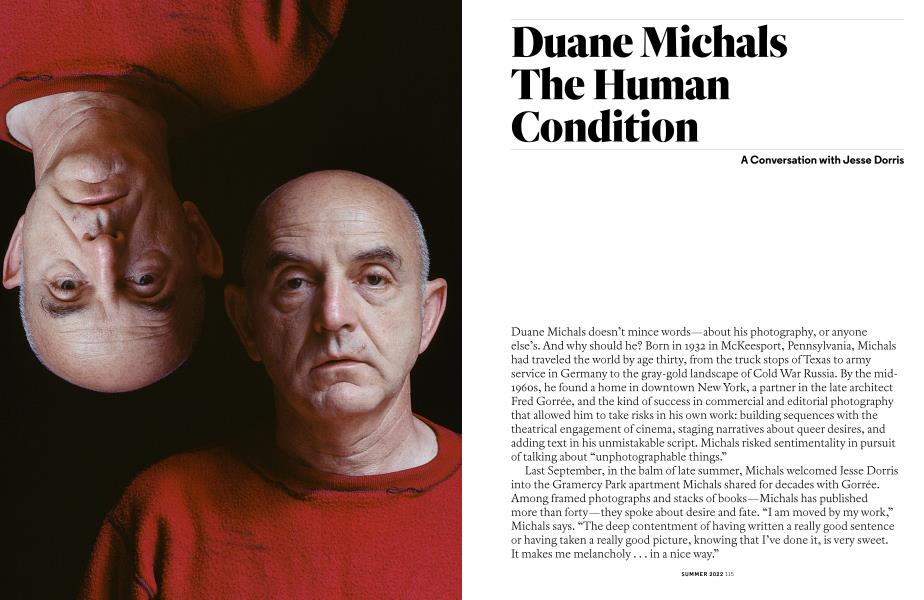

Duane Michals The Human Condition

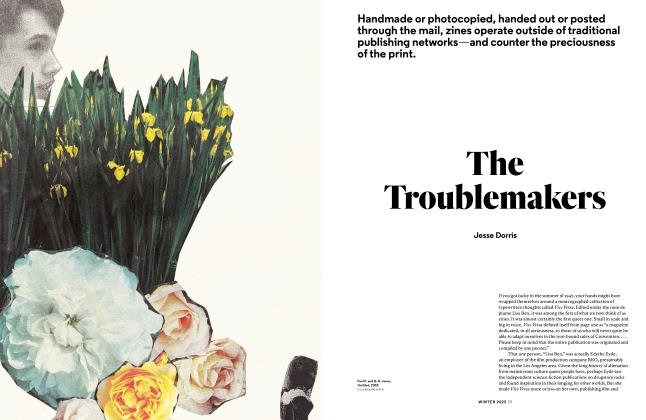

Jesse Dorris

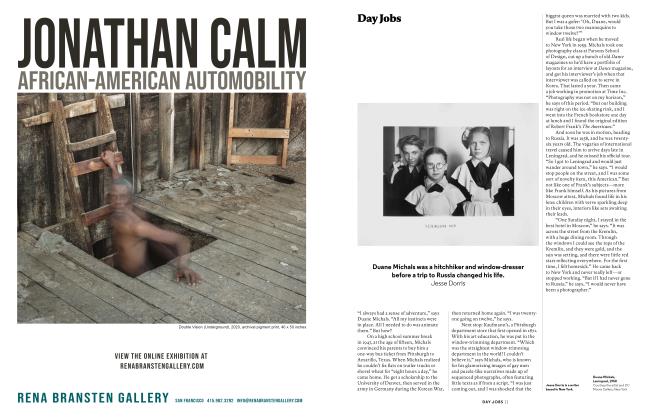

Duane Michals doesn’t mince words—about his photography, or anyone else’s. And why should he? Born in 1932 in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, Michals had traveled the world by age thirty, from the truck stops of Texas to army service in Germany to the gray-gold landscape of Cold War Russia. By the mid1960s, he found a home in downtown New York, a partner in the late architect Fred Gorree, and the kind of success in commercial and editorial photography that allowed him to take risks in his own work: building sequences with the theatrical engagement of cinema, staging narratives about queer desires, and adding text in his unmistakable script. Michals risked sentimentality in pursuit of talking about “unphotographable things.”

Last September, in the balm of late summer, Michals welcomed Jesse Dorris into the Gramercy Park apartment Michals shared for decades with Gorree. Among framed photographs and stacks of books—Michals has published more than forty—they spoke about desire and fate. “I am moved by my work,” Michals says. “The deep contentment of having written a really good sentence or having taken a really good picture, knowing that I’ve done it, is very sweet.

It makes me melancholy... in a nice way.”

Jesse Dorris: What’s the difference between luck and fate?

Duane Michals: Fate is fate. You’re predestined. This conversation was destined to happen. We’re just fulfilling the destiny.

I don’t believe in that. I believe in accidents. I believe in spontaneous combustion. I believe that every second we’re inventing a new universe. I believe in ... [S/ngs] “I believe in magic ...” I also have a song for every occasion.

JD: I’m curious as to how you make the decision between staging a moment and willing something to happen, or setting up an occasion and just letting something magical happen, or going out and stumbling upon something.

DM: Instinct. I trust my instinct more than I trust me. I’m completely unreliable. I wouldn’t trust me if my life depended on it. I’m going to my hometown in McKeesport, making a movie this weekend. McKeesport has fallen on hard times. It’s collapsed. Imploded. I used to go to the library all the time. I once took out a book nine times, and they wouldn’t let me have it anymore.

I never got over it.

JD: What was the book?

DM: It was called Cities of America. There were photographs of every major city. I wasn’t interested in photography. I was interested in the cities. Fred and I had a house in the country for forty-four years, near Bennington, in the woods. I used to build model cities in the woods.

JD: Did you ever strike up a more architectural practice with your photography?

DM: Oh, no. Fred was an architect, and that was one of the reasons why I was enchanted by him—because I wanted to be an architect. He worked for Marcel Breuer for a long time, then he worked for Skidmore, Owings Merrill, then he went on his own. But he was never ambitious. He was more of a homebody.

I was always ambitious. Buddhists say... the Hindus say (excuse me, wrong sect) that in life you want just enough—not too much, not too little, just enough. I’ve had just enough ambition to not become Mapplethorpe, who, I felt, for somebody so “professionally gay,” had very little insight on the subject. I had a long-term relationship with my Fred—and we were also gay. My whole life has been just enough.

I’m telling you what the event was. It’s not an observation. I’ve expanded the photograph from being a silent object

JD: How do you know it’s just enough?

DM: It suits me. I have wonderful instincts. I am not hip, I am not cool, but I am charming.

JD: We’re in this time where we are expected to make self-portraits of ourselves all the time...

DM: That’s why it’s called “self-portrait.”

JD: Yes, exactly. For Instagram, for dating profiles, for professional reasons, we’re always expected to be able to make these representations of ourselves. How do you take a self-portrait that is expressive of yourself?

DM: I feel that you become the artist when you bring insight. It’s one thing to photograph somebody, but it’s another thing to bring insight, to annotate, to expand the moment of expression. Because, ultimately, portraiture is simply anatomy, and people like portraits mainly because they think they might look good. I once photographed a guy, and I heard he loved the picture. Then I heard he liked it because his nose looked small. No matter what the picture looked like, all he saw was a nose. Any picture of me where I look bald, I’m not thrilled.

JD: Do you sleep well?

DM: As Marilyn Monroe said so succinctly,

I sleep with the radio on.

JD: I do too.

DM: Nothing in life prepares you for being old. Being old should be a reward, not a punishment. The only regret I will have when I die is that I will miss all the work I haven’t done. But also, the other thing said about being old is that you must have more regrets. I have done everything—not everyone—but everything that I’ve always wanted to do.

JD: You’ve done everything you’ve always wanted to do?

DM: Yes. I’ve been everywhere, done everything... I won’t travel anymore.

I made about forty-one mini-movies.

I have no ambitions for Hollywood. But if a studio called and said, “We have an extra three million dollars laying around. Would you like to play with it?” Of course,

I would say yes. I always say, “I shoot first and ask questions later.” I don’t procrastinate.

J D: How do you not procrastinate?

DM: I have a huge curiosity. Everything is about curiosity. And if you have no curiosity, then go watch television and jack off, or jack off and then watch television.

JD: It depends on what you’re watching.

DM: Exactly. Good. You’re keeping up.

JD: It seems that curiosity is, maybe, what has propelled you to push the forms of your work.

DM: Oh, always. Another quote for you is: “You are either defined by the medium or you’re redefining the medium.” And I redefined photography. When I came on the scene, the definition of photography was “reportage, reportage, documentation.” That was it. And portraiture. When I had an exhibition called Sequences at the Underground Gallery, Garry Winogrand came, and he said to me, “What is this? This isn’t photography.” I thought, Well, that’s not your photography. But in those days, I didn’t realize how it was considered a no-no. Completely. Then, when I began to write on photographs, I ran into a teacher from the School of Visual Arts, and he said, “What are you doing? The scuttlebutt at school is that your photographs are so bad you have to write under them to explain them.” I said, “Tell them in five years they’re all going to be writing on photographs.” The thing is that it’s so simple. Text has always gone with pictures. You pick up a Daily News and there is a picture of Donald Trump as he falls down a flight of steps off of Air Force One and breaks his hair. The caption tells you what you see. I was the news editor on our high-school paper. So I write with the photographs to tell you what you can’t see. Photographs fail constantly.

JD: Do you think that some of the resistance to that was because you’re asserting that photographs are failures?

DM: Yes.

JD: That there are things that photography can’t do.

DM: Totally. I did Empty New York in the mid-1960s inspired by Atget, and then I did a shot of a bar on Third Avenue, and the title of the picture was There Are Things Here Not Seen in This Photograph (1977).

The text says something like: “It was a very hot day. I come into the bar. I want a beer. I notice there’s a cockroach going up the stool leg of the bar. On the jukebox somebody was singing ‘Southern Nights.’ Two drunks are arguing about Nixon in the corner. A bum was coming toward me to ask for money. It’s time to leave.”

JD: Why do you want viewers of the photographs to know all of those things?

DM: Because I am doing a story, and it’s setting the stage. It’s a total environment. I’m giving you the hum, the noise, the street sound. I’m telling you what the event was. It’s not an observation. I’m sharing an event. I’ve expanded the photograph from being a silent object.

My other thing is: Don’t tell me what I already know. Contradict me.

I just did an article for the Queer Critique Group of Baxter Street and I ended it with: “Picture this. A room. A dark room.

In the room are a table, chair, and a bed. Two naked men are standing there. Very, very close to each other. They’re almost touching. And then what happens?” I love the premise. Because the photographer doesn’t give me then what happened. The photographer shows me the two guys standing there.

JD: Your work very much seems to be acknowledging and celebrating sex and sexuality.

DM: Yes, absolutely.

JD: But it’s not about...

DM: It’s not about sexual acts.

JD: Did you ever think you should take photographs of the acts? Did you ever want to make that a moment in your career?

DM: No, not at all.

JD: Why not?

DM: Because it’s been done so many times.

JD: But you could have done it first.

DM: No, I wouldn’t have done it first.

I love the theater. I like the drama. I did a book called Homage to Cavafy (1978). The first picture is about the father who has died. This happened to me. I was in Vienna. I came home. Fred took me to dinner Sunday night and he said, “Your father died.” I was too late. So, it’s a supposedly dead father in bed, and the son, nude, is sitting next to him in a chair, and the son has one hand in a fist and the other hand open—the fist, for me, is symbolic of the conflict between them, and the hand open is wanting to touch him and acknowledge him.

JD: Why is the son nude?

DM: It’s a gay book. Right? You ask me why I’m not photographing dicks, then you say to me, “Why is the son nude?” There’s another one of an empty room, because I see empty rooms as a theater set. If you put too much information, it distracts. So a guy is in an empty room— a beautiful guy. He’s pulling his shirt off. The caption says, in effect, “He did not realize it, but at the very moment that he had pulled it off, he had reached his peak, and after that moment he would begin to decline.” We don’t even know it, but there’s always that moment when we have fulfilled our physical expectations. I did another picture, in that same book. It’s a room, again. A window. A big fat guy; a bald guy holding up a picture of himself as a young man. And there’s a cat on the ledge. And the caption says: “When he was a young man, it was impossible that he might grow old. Now that he’s old, he cannot remember ever having been young.”

That was perfect. But tell me one other fucking gay photographer who ever talked about old age.

JD: Tell me where you fit into the gay spectrum.

DM: My mother got knocked up in 1931.

She had to marry my dad. She didn’t like him, but they were Catholics. So my father was a no-show. He was there, but he wasn’t there. When I was in high school there was Stuart Middleman, and Stuart Middleman was a sissy. He carried his books like this, and he hung out with the girls. You didn’t want to be Stuart.

Dreaming is magical We die every night. We don’t exist when we’re in dreamland.

But there was no “gay.” I didn’t even know what that was. That’s all I knew. And I knew there were queers, but I wasn’t quite sure what that was. I was always interested in an older man who would show an interest in me. I would have killed to have an older man put his arm around my shoulder and say, “Gee, Duane, that’s good. Did you write that? That’s amazing. Keep doing it.” Nothing ugly. Fred was the first.

Fred was a year older than I was, but I never found that older male affection.

I was never interested in going to bars.

I was never interested in pretending I’m a woman, dressing up in drag. Nothing like that. I think it’s legitimate, but not forme.

JD: I’m interested that you weren’t, because of your interest in theater and the Grand Guignol and all of that.

DM: I was interested in writing. I was interested in the drama. I wasn’t interested in the costumes. There’s a big difference.

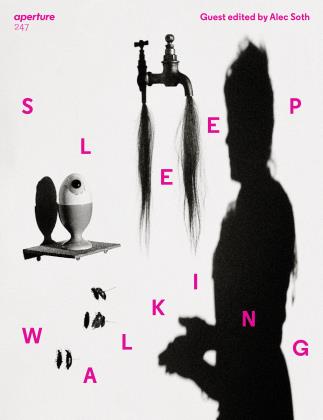

JD: I want to talk to you about the use of sleeping in your photography, in The Fallen Angel (1968) and The Bogeyman (1973). You were saying you want to show things that can’t be seen.

DM: Yes.

JD: And sleep, in a way, is where you can’t explain what you see. You’re vanished.

DM: We spend one third of our lives sleeping. A very early book I did in the 1980s was called Sleep and Dream (1984). Dreaming is magical. We die every night. We don’t exist when we’re in dreamland. When you’re in dreamland, the most amazing things happen. When I visited Magritte, every day we would have lunch, and Bonanza would be playing on television dubbed in French, and he would take a nap—and I photographed him asleep on the sofa. He always wore a suit.

JD: Did he know you were photographing him while he was napping?

DM: Oh, no. He just gave me run of the house, which was amazing. I thought: I wonder what kind of dreams could Magritte have? What kind of dreams did Shakespeare have? Some people have more interesting dreams than they have lives while awake.

JD: Have you had lucid dreams?

DM: Only once ... or twice ... and I never got over it. I was walking down the street and on the corner was A1 Seymour. I knew A1 was dead. In the dream, I thought to myself, There’s A1 Seymour, but he’s dead.

I woke up and said, Wait a minute, I’m in a dream. So then, in the dream scenario, I was supposed to cross the street, but I wanted to go this way. I wanted to take over the dream. But I couldn’t do it.

JD: But that’s sort of photography, right? Taking over the dream? Directing.

DM: Not directing, but curiosity more than photography. But then I wondered: What if I wander down that street, and, if I couldn’t find my way back to that same corner, I would never wake up?

JD: Do you think that would have been true?

DM: I can’t say I can’t wait to die, but I’m curious about it. I’ve done so many things about death. In the first sequence book I did in 1969, Death Comes to the Old Lady, the spirit leaves the body. And I did one where the guy in the subway becomes a star. The second book I did was called The Journey of the Spirit After Death (1971), based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

JD: Did you ever worry that you’re sort of tempting... I know you don’t believe in fate. But sort of tempting fate by manifesting these moments?

DM: No.

JD: It never bothered you?

DM: No, I don’t believe in that at all. Because we make up life, and life is one moment. If you believe in some sort of predestination, then why bother? I think we’re masters of our own fate, and if we’re not brave enough to seize the moment, then that’s what you get.

JD: What was it about sleep that caught you so intensely that you made a book?

DM: Oh, because I think the dreamworld is a legitimate world. Do the math. If we live for, say, sixty years, and one third of sixty would be twenty, then we sleep twenty years of our lives. And that’s not worth the curiosity?

JD: Do you believe in what they call “dream logic,” that there’s a language...

DM: Yeah, the theater of the dream?

JD: Yeah, that we don’t understand.

DM: I do. I think it has its own reality.

It has its own rules. It’s a whole other planet.

JD: How do you get the people in your photographs to do what you want them to do?

DM: I say, “Sit there.”

JD:And do they?

DM: Yes.

JD: Because you’re charming?

DM: No. First of all, the people in your photographs do not know what you want.

I have to tell them. I hate those people who just walk around, and they snap.

No. You take charge. Like, again, Garry Winogrand was a snapshooter. He shot, like, five thousand rolls of film he never even looked at. He liked to take pictures, and all the pictures he took were accidents.

JD: But what’s the difference between an accident and chance?

DM: It’s the same thing. An accident is chance. Chance is an accident.

JD: Do you have thousands of rolls of film?

DM: No. For myself, I shoot very, very little. Elaine May made her movie Ishtar (1987), and they took a break, and the cameraman said to her, “While you’re taking lunch, do you want me to keep the cameras going?” She said, “Yeah, something might happen.” Shakespeare didn’t wait for something to happen. Real artists take charge. They make it happen—with latitude. I make things happen. When I go to McKeesport,

I might expect something to happen I’m not counting on, and I will use it. But I come with a frame of reference.

JD: You have to set it up first.

DM: Yes. So I set up the premise, and then, my challenge to the young photographer is: Now, tell me what happened.

JD: What if they don’t know?

DM: Then fuck them. I don’t care what they do. Figure it out. That’s their job. Their problem is, they don’t know. They do not know that knowing is an option. Nobody teaches you that it’s an option.

JD: That’s really true.

DM: My great thing was, I never went to photography school. I’d have to unlearn everything.

JD: I’m thinking now of you beginning to write on your photographs, and I’m wondering how your handwriting looked to you.

DM: Oh, I don’t pay attention. It looks as it is. And don’t forget: I was a graphic designer, so I have a sense of the appropriateness of things.

JD: Did your handwriting change as you did it over the years?

DM: Essentially, no. But now I try to write better. It always gets described that my handwriting is “chicken scrawl.”

JD: So why didn’t you make your scripts beautiful?

DM: Because it’s not about beauty. It’s about intelligence.

JD: Which brings us to your use of double exposures. How does that go wrong?

DM: Oh, because you could be lousy. I discovered double exposures when I went to Russia with my thirteen-dollar borrowed Argus—because it double exposed gratuitously. Then I began to look at these double exposures, and I said, “That’s good. That’s interesting.” So I began to control it. Like that picture I did called The Illuminated Man (1968). That just didn’t happen. I had that in my head. I was meditating. I knew that when you went up to Park between 34th and 42nd, there’s a tunnel, and cabs go down it, and I would see these spotlights coming in. So I took my friend Ted Titolo— he’s in all my early pictures, he’s also in Chance Meeting (1970)—I put him in the tunnel on a Sunday, when there was very little traffic, and I stationed him so the sun would hit his face. Then I exposed for the tunnel, which means his face would be way overexposed and blur out on purpose. The spirit leaves the body. It’s totally controlled.

JD: It’s a transcendence that’s totally controlled?

DM: Yes. It freed me to another level of expression. Everything I’ve done has been to free me from the shackles of photography.

JD: It frees you how?

DM: The bottom line is expression. It’s not technique. Technique is at the service of expression. People get hung up on technique and have nothing to express. I didn’t start out wanting to be a photographer. I came to New York because I loved books and magazines, and I wanted to get a job as a designer. Henry Wolf was the great art director those days, and there was an opening at Harper’s Bazaar. So I made two magazines for my portfolio. I made one based on Du, my favorite Swiss magazine, where they do a whole issue on a single subject. And I invented a magazine called Contact. It was contact with life, contact with theater, contact with art, contact with poetry. I did a whole issue on Russia, using my own photographs. When I showed it to Henry, he said, “Who took the pictures?”

I said, “I did.” He said, “Oh, you should be a photographer.” He wouldn’t hire me. But when he went to Show a year later to be the art director, he hired me for the first issue. Then I went to see Lou Silverstein, the legendary art director of the New York Times. He wouldn’t hire me as a designer. But, eventually, he gave me a variety of things to shoot for the Times, including the annual report.

JD: Did your partner Fred’s Alzheimer’s affect the way you think about language?

DM: Not at all. I do think about how I think but never while I’m thinking. I don’t pay attention to it. I’m completely on automatic. I don’t think about the act of writing. The best time for me to have ideas is when I wake up. Seven to nine is when my mind is just throwing things at me.

JD: Is that because of sleep? Everything’s been stored up?

DM: I don’t ask. And I don’t tell.

JD: Did you photograph Fred at the end?

I do think about how I think but never when I’m thinking. I’m completely on automatic.

DM: No. Are you kidding?

JD: People make work out of all kinds of things.

DM: Avedon made photographs of his father when he was dying and published them a year later. But there are times you don’t take a picture. I would never photograph Fred while he was dying. Oh my God. The last thing I would do. How could that part of your brain kick in when the great love of your life is dying? We had fifty-seven years together and I’m going to start:

“Fred, would you hold that pose? Open your mouth more, please. No, keep the eyes shut. No gurgling noise. I’m trying to take a picture.” Nonsense.

JD: I think for some people that is how they process their lives.

DM: I can’t. [Sings] “Some people can thrive and bloom / living life in the living room.” Best Stephen Sondheim song ever. “Some people can be content / playing bingo and paying rent. That’s peachy for some people.” All my friends in McKeesport were living—are still living— lives in the living room. I burned the living room down.

JD: You were never typical.

DM: Fred and I were never typical gay people of our generation. When we bought a house, we lived in the country.

We didn’t go to Fire Island. We didn’t go to the Hamptons. We didn’t do any of that. We bought a farmhouse with lots of land. We’re big gardeners. That’s one of the things we had in common. What works is, the more you have in common with somebody, the better it is for the relationship. Opposites don’t attract. It’s about the more you share. Fred was the great love of my life. And all relationships evolve. Nobody lives happily ever after.

We avoided all the pitfalls.

JD: How?

DM: Well, very easily—because we had other issues in our lives. We weren’t dick focused. Of course, we were dick focused. But when I wasn’t around, I didn’t have to worry that Fred was hanging out in a bar.

JD: Were you monogamous?

DM: No. But eventually, we evolved. I think because we shared so much ...

JD: And you not photographing him?

Do you think that might have helped?

DM: It was never an issue. We kept our lives separate. I learned early on that we didn’t work that way. Have I out-talked you? I’ll show you pictures. This is Fred and myself in happier days. That’s Fred, that’s me.

JD: Oh, you’re so handsome.

DM: This is the last time Fred was in the country. There’s our garden. Then this is Fred when he had Alzheimer’s. That’s Fred and me here. This is Fred at the end. Sit down. I wrote something very nice about him. I wrote a poem. It said: “Dear Friend, / If you should die before me, /1 would build you a pyramid, / And each stone would be a memory / Of a moment we had shared. / And I would remember you. // And when you awaken / From your dream of death / Should you chance to find / This pyramid in your travels, / Remember me, / And how I once loved you long ago.” It always breaks my heart.

JD: Duane, that’s so beautiful. Did you publish that somewhere?

DM: It’s from when I sent out Fred’s death notice.

JD: It’s just gorgeous.

DM: Here, you can have a copy.

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York and a regular contributor to Aperture, Metropolis, and PIN-UP.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue