In May 1984, when Sprouse showed his latest collection at the Ritz, a former club downtown, 2,500 people attended, including Andy Warhol. He loved Sprouse’s sixties-inspired clothes and afterward traded two portraits for the whole collection. “Sprouse was definitely one of Andy’s ‘children,’ ” says Benjamin Liu, who worked as Warhol’s assistant. “So much of what Andy was brilliantly known for—the neon colors, the Pop imagery, the association with musicians—Stephen brought into his own work.” Warhol, in turn, brought Sprouse into his life, inviting him for dinners at Odeon or Indochine that would lead to after-dinner excursions to Area, at the time the city’s hottest club.

Jean Pagliuso for American Vogue, November 1984

Steven Meisel for American Vogue, March 1988.

Spanish Vogue, Stephen Sprouse in the middle .

Sprouse had been in business only a short time but had quickly become a cult figure, his clothes prominently featured in major department stores and on the pages of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. He was part of Warhol’s coterie. Rock stars, like Madonna, wanted him to help style their images. But there was one way in which success eluded him: He was running out of money. From Halston, he’d developed a taste for expensive materials, but since no one was making Day-Glo fabric at the time, he turned to Agnona, the Italian luxury cashmere manufacturer. As a result, his clothes were priced too high for the youthful customers who gravitated to them. Then there were the production problems, as Sprouse insisted on doing things like hand-painting the graffiti on the clothes himself. By the spring of 1985, he owed $600,000 to creditors; that summer, Sprouse shut down his business.

The press had a different kind of field day, and stories appeared with headlines like SPROUSE: HOW SUCCESS TURNED TO FAILURE. Sprouse, for the most part, kept his feelings private.

In September 1987, six months after he’d designed costumes for the New York City Ballet’s premiere of Ecstatic Orange—and after the sudden death of Warhol, who was buried in a Sprouse suit—Sprouse returned to fashion with the opening of his own store in a converted firehouse on Wooster Street. He was now in business with 24-year-old Andrew Cogan, whose father, Marshall, was chairman of GFI-International. At last, he had big money behind him. But the store was a risky venture—he would be the first designer to have a full-scale emporium in Soho. “There was nothing like this downtown,” says longtime friend Candy Pratts Price. “It was a real happening. A living environment.”

.

Sprouse controlled almost every aspect, designing the interior, picking out the music, selecting the images for the massive video wall on the first floor. He created three different clothing lines, including a cheaper one for younger customers, as well as gloves, fishnets, hats, shoes, jewelry, even makeup. “The opening was unbelievable,” says Jamie Boud, Sprouse’s longtime assistant. “Debbie Harry played on a stage formed by a big red X. Stephen knew a lot of people, and they all showed up for him.”

He did two shows that year, one grown-up and sophisticated, with prints done in collaboration with Keith Haring, the other a Sprouse phantasmagoria, with models stumbling down the runway chewing capsules that gushed fake blood. “That show was critisized harshly ,” says Boud. “But Stephen thought it was the best one he’d ever done. He was into the showbiz of it all. The clothes were just costumes for the ‘show.’ ”

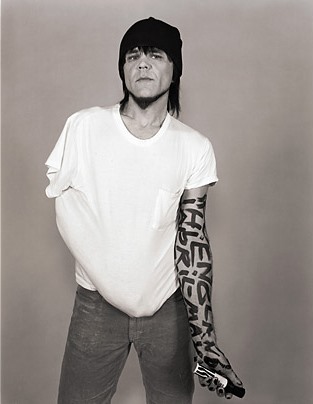

By 1989, Sprouse, in what was now becoming a familiar pattern, was once again unemployed. He lost his stores—he’d opened a second one in L.A.—and his wholesale business. “We were too crazily, overly ambitious,” admits Cogan. “At the end, we were doing close to $10 million worth of business, but it wasn’t enough. The clothing, particularly after that last show, which was a spectacular bomb, didn’t sell. Telling Stephen we couldn’t continue was the worst day of my life.” “After the store closed, Stephen was a little lost,” says Boud. “He was just a freelance guy at that point. He realized fashion was what he was best known for, but nothing about his career had ever been calculated.” He spent more time on his art, creating giant silk screens of rock stars, like Iggy Pop and Sid Vicious. He made costumes for Mick Jagger, Axl Rose, Trent Reznor, Courtney Love, David Bowie, and Duran Duran, and designed numerous album covers and backdrops for sets.

In 1996, Sprouse won the rights to use Warhol’s imagery on his clothing, which led to a deal with Staff International, an Italian company whose stable of designers included Vivienne Westwood. Sprouse returned to the runway in the fall of 1997 with a collection that paid homage to Warhol: Models wore the artist’s vivid Pop images on dresses and baggy raver-style pants. But when Staff was later bought out by another company, Sprouse’s license wasn’t renewed—a cruel irony, as fashion was then experiencing a retro-eighties moment and Sprouse’s designs were fetching high prices at vintage stores.

In the summer of 2000, Marc Jacobs asked Sprouse to go to Paris to help with his spring collection for Louis Vuitton. Jacobs, who’d known Sprouse from his own club days, had long been a fan, and arranged for him to stay at the Ritz, where Sprouse, staring at TV static one night, came up with the idea of creating floral prints using huge digitized cabbage roses. But it was Sprouse’s graffiti bag, on which he’d written, in raw painted lettering, louis vuitton paris, that became the big hit, with long waiting lists. Sprouse confided to Boud that even he couldn’t get one. Months later, he could—on Canal Street, where counterfeiters were selling them by the hundreds. “At least the knockoffs were expensive,” says Boud. “Other bags by other designers were selling for $20; his were $90.” Friends bought the standard LV knockoffs and asked Sprouse to paint graffiti on them.

In the summer of 2000, Marc Jacobs asked Sprouse to go to Paris to help with his spring collection for Louis Vuitton. Jacobs, who’d known Sprouse from his own club days, had long been a fan, and arranged for him to stay at the Ritz, where Sprouse, staring at TV static one night, came up with the idea of creating floral prints using huge digitized cabbage roses. But it was Sprouse’s graffiti bag, on which he’d written, in raw painted lettering, louis vuitton paris, that became the big hit, with long waiting lists. Sprouse confided to Boud that even he couldn’t get one. Months later, he could—on Canal Street, where counterfeiters were selling them by the hundreds. “At least the knockoffs were expensive,” says Boud. “Other bags by other designers were selling for $20; his were $90.” Friends bought the standard LV knockoffs and asked Sprouse to paint graffiti on them.

Backstage with Marc Jacobs at the Louis Vuitton s/s 2001 show .

The experience with Marc Jacobs disillusioned Sprouse on fashion; instead of coming away envious of Jacobs’s lucrative LVMH deal, he realized he’d never be able to work in such a rigid corporate structure. Though Sprouse was then in his late forties, he was still very childlike and loved sitting in Washington Square Park, watching the kids skateboard.

In 2002, Sprouse designed a lower-priced line of red, white, and blue clothing and accessories for Target. Everything had usa written on it in graffiti print. While some people viewed it cynically as a cheap way of cashing in on 9/11, Sprouse, who’d lost a friend in one of the plane crashes, felt an uncharacteristic surge of patriotism.

For years, friends had noticed that Sprouse, who smoked three packs of cigarettes a day, seemed frequently out of breath. At the end of 2002 Sprouse asked around for rehabs for cigarette smokers. He wanted to go to a place where they’d lock him up. Finally, Sprouse quit cold turkey, but in spring 2003, he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

Sprouse kept his diagnosis a secret from all but a few friends. Andrew Cogan, who by then had become CEO of Knoll, had hired him to do textiles, and Renzo Rosso, the founder of Diesel, wanted him to design T-shirts and jeans. He was very concerned about losing those contracts.

A friend took him to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston and managed to get him admitted into an experimental drug trial, but when his breathing worsened, doctors wouldn’t let him continue with the protocol. Over the next eight months, he visited numerous oncologists and took various drugs, hoping to improve enough to be readmitted into the Dana-Farber program. One drug gave him such bad acne he didn’t want anyone to see him. In September 2003, though, he had to put in an appearance at the opening of the new Diesel store he’d helped to design on Union Square.

Yet he had his optimistic moments, as if cancer were just another business reversal from which he could stage a triumphant comeback. He put his energy into painting portraits of his friends and nephews. He was even working on a painting of the space station for NASA.

In January 2004, he took a six-week trip to Buenos Aires to visit a friend. A few days after his return, Sprouse couldn’t catch his breath. He called a friend, Sean Bohary, who took him to St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital, where he died early the next morning.

In Paris, the fall 2004 shows were in full swing, with people saying an emotional farewell to designer Tom Ford, acting as if he’d died when he was only leaving Gucci. On Sunday night at the Vuitton show, tucked inside the program, people found a slip of paper that read, “This collection is in loving memory of our friend Stephen Sprouse.”

On March 10, 25 friends gathered in New Jersey for the cremation. With pens and Magic Markers, they covered his wooden coffin in graffiti, writing messages to him on the inside and outside surfaces of the box. Then, before closing the lid, someone placed a Magic Marker in Sprouse’s hand, so he could write the last words himself.

.

.

Book

The Stephen Sprouse Book

Inventive, enigmatic, and supremely creative, Stephen Sprouse made art and clothing that captured the mood of the eighties. One of the first American designers to mix graffiti and a punk aesthetic with fashion, Sprouse manipulated conventional notions of style, and his unique sensibility has inspired designers from John Galliano to Raf Simmons to Marc Jacobs. Sprouse’s career started in the late seventies, when, after working for Halston, he migrated to a warehouse on the Bowery and started making outfits for his neighbor, Debbie Harry. The fashion world quickly embraced his innovative, culturally relevant sensibility and downtown edge. But Sprouse’s inability to compromise his artistic vision for the rigid fashion business compromised his commercial success. The Padilhas possess the largest private collection of Sprouse’s work, and were given exclusive access to his archives by his family for this project. They also obtained never-before-published images from photographers such as Steven Meisel, Bob Gruen, and Mert and Marcus. The book features a foreword by the novelist Tama Janowitz, one of Sprouse’s closest friends. The release of this book coincides with a retrospective at Deitch Projects. The book will be available with four different jackets, each featuring a different Day-Glo color, an homage to Sprouse’s iconic album cover for Debbie Harry’s Rockbird.

http://www.thestephensprousebook.com

.

.

info: WikiPedia

http://nymag.com/nymetro/arts by Patricia Morrisroe

this is one of my two favorite blogs, & definitely my favorite fashion blog :-} .

Unfortunately our system – even if it notices them and it usually does because they make such important contributions – does not celebrate artists that are not embracing that very system or that are not combatible with it. It is a common problem even today. The big brands hire folks who are fashion conscious and possible fashion addicts and able to adjust within the bounderies, but they simply borrow from the street and the designers and artists which do not see themselves part of that system – the fashion industry – there may be a few exceptions but in general people like Steven Sprouse are completely overlooked. I am just glad that his name is known and that he gets some credit, but boy is it unfair to let him go through this stressful scenario and then gotta die prematurely.