Stephen Sprouse by Andy Warhol, 1987 .

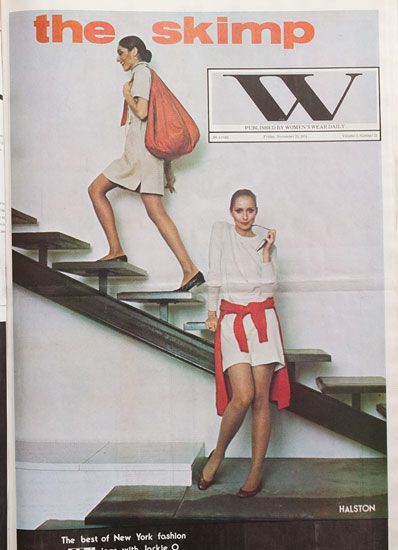

When Stephen Sprouse was working for Halston in the early seventies, he liked to tease the designer. “Okay, here we go,” he’d say. “Another shirtdress for the old ladies.” Sprouse loved Carnaby Street and miniskirts. He wanted to see women’s legs again, and pestered Halston constantly about it. Finally, two days before a major New York show in 1974, Halston let Sprouse have his way. “We rolled a big fat joint,” says the actor Dennis Christopher (another of the designer’s “Halstonettes”), “and Halston said, ‘Do it!’ Stephen picked up a pair of giant shears and began cutting off the bottoms of the dresses.” Christopher soon joined in, and with Halston crying, “Skimp it, skimp it!,” they created what became known as the Skimp.

Stephen Sprouse was born in 1953. Being the oldest son of Norbert and Joanne Sprouse, he spent his first two years in Dayton, Ohio, where his father was stationed at the Air Force base. After the family moved to Columbus, Indiana, Norbert Sprouse pursued a lucrative manufacturing career; the family lived comfortably in a white, columned house a friend describes as something out of Gone With the Wind. Sprouse’s artistic talent emerged when he was a toddler. “Stephen was wired the way he was from the time he was 2,” his mother says. “He was totally unique.”

He was rarely without a pen, churning out pictures with such intensity that his mother worried that her shy son was relying too much on his art to do his talking. Sprouse was assertive only when wielding a pen or pencil—and then so much so that teachers nicknamed him the Art Supervisor. At 9, he drew a series of four self-portraits, in which he imagined his future career choices. “I might be a hobo,” he printed beneath one. “Or a movie star . . . or a father.” On the last picture, as if acknowledging his special gifts, he wrote, “Now I know who I better be—ME!”

When Sprouse was 12, his father showed his portfolio to someone at the Art Institute of Chicago, which led to an introduction to the designer Norman Norell. Sprouse’s father took Stephen to New York to meet both Norell and the Indiana-born Bill Blass, who later hired the aspiring artist as a summer apprentice. Sprouse was then only 14. “He was cool, my dad,” Sprouse told the late fashion editor Amy Spindler. “I mean, this was in Indiana. He could have beat me up if I didn’t play football, and he didn’t.”

Four years later, Sprouse enrolled at the Rhode Island School of Design, where a teacher introduced him as “the designer of the future” to a class that included Nicole Miller. For Sprouse, however, the future couldn’t come soon enough, and he left after three months to come to New York. He was totally fascinated by Andy Warhol and the people who hung around him. Sprouse loved Edie Sedgwick. For him, she was like the sixties Kate Moss.

Assisting Halston with a fitting on Anjelica Houston, 1970s .

Sprouse immediately got a job with Halston, who was then at the height of his fame as America’s top fashion designer, and a reigning prince of Manhattan’s nightlife. Sprouse as a “total drawing machine.” Halston frequently designed by draping fabric, and Sprouse, sketchpad in hand, would have to visualize the architecture of his draping and then translate it to paper. Other times Halston would simply say, “Now, give me a dolman sleeve,” and Sprouse would instantly create one. From Halston, whose strength as a designer was in the purity and simplicity of his forms, Sprouse learned about shape and luxury.

Sprouse left Halston after two and a half years, and in 1975, he moved to a loft in the Bowery, where he shared a bathroom and kitchen with singer Deborah Harry. The beautiful ex–Playboy Bunny, and former art student Chris Stein had recently formed Blondie, and they were beginning to gain a following at Max’s Kansas City and CBGB. At Halston, Sprouse had loved playing dress-up with the designer’s favorite model, Karen Bjornson, who personified the cool Upper East Side blonde. He transformed Harry into a kind of Bowery Bjornson, creating clothes from ripped tights, T-shirts, and objects he picked up off the streets. In London, designer Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, manager of the Sex Pistols, were already making the conceptual link between fashion and punk with their Kings Road boutique, Sex. It sold slashed T-shirts and bondage gear. Sprouse’s vision was less hard-core, more glam. He may have created a dress with razor blades dangling from the hem, but it was beautifully designed.

Debbie Harry wearing Sprouse, 1979

Debbie Harry & Stephen Sprouse .

Art, rock music, and fashion were the central themes of Sprouse’s life. When he wasn’t designing clothes, he worked on his art, doing giant silk-screen paintings of rock stars, and painting pictures over the Xerox copies he made with his large industrial copier. With the advent of music video, rock and roll was becoming a bigger part of mass culture. In 1978, he photo-printed a picture he’d taken of TV scan lines onto a piece of fabric, which he then designed as a dress for Debbie Harry. She wore it in the video for her No. 1 hit “Heart of Glass,” giving Sprouse the kind of exposure it had taken Halston years to get.

Sprouse found many of his design ideas on the downtown club scene. He was a regular at the Mudd Club, where the “theme parties”—the equivalent of happenings in the sixties—attracted both an art and a music crowd. It was viewed as the antithesis of Studio 54, which, in Sprouse’s mind, was more Halston’s territory. One thing both places had in common, however, was the copious quantities of drugs being consumed on their premises. Pot was Sprouse’s drug of choice during the Halston years, but he later moved on to heroin. Friends say that if he hadn’t stopped, it would have killed him, but he went into AA. He wasn’t about to become a drug victim. His work meant too much to him.

Debbie Harry in early Stephen Sprouse dress

Debbie Harry in early Stephen Sprouse dress

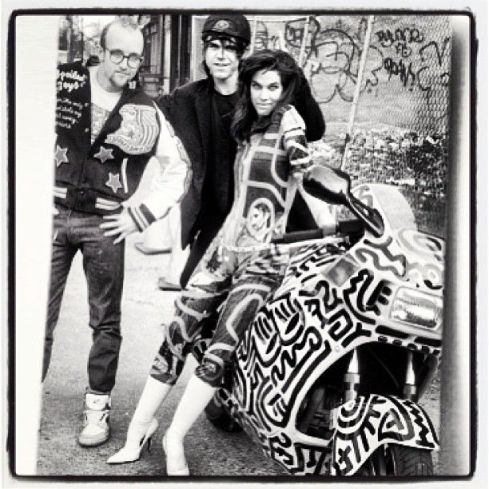

Keith Haring, Stephen Sprouse & Teri Toye

Keith Haring, Stephen Sprouse & Teri Toye

.

For years, Sprouse had been adorning his hands and arms with friends’ phone numbers—his version of a Palm Pilot. Graffiti, both an essential element of punk and an outgrowth of subway art, had already been incorporated into the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. Sprouse decided to use it his way.

“Stephen told me that he was wandering around the East Village one day,” says Beyer, “and suddenly went home and began sketching graffiti-covered motorcycle jackets and sequined miniskirts.” He showed them to his friend Steven Meisel, then an aspiring photographer, who brought them to fashion producer Kezia Keeble. In April 1983, Sprouse’s clothes appeared in a show of young designers that Keeble produced and were such a hit that Bergdorf Goodman and Henri Bendel immediately ordered ten dresses. He was suddenly a bona fide fashion designer—something he wasn’t entirely sure he wanted—and with $1.4 million from his parents, he set up his business.

Muse Teri Toye modeling Stephen Sprouse .

Eight months later, at his silver-painted showroom on 57th Street, he introduced his first, groundbreaking collection, a synthesis of sixties and eighties pop culture, which merged all the visual references he’d picked up on during his thirteen years in New York. The models wore big Jackie O sunglasses, impish stocking caps, and graffiti-covered white motorcycle jackets, while punk rock and the Rolling Stones boomed from speakers. “I remember being totally overwhelmed,” says Kal Ruttenstein, now Bloomingdale’s senior vice-president for fashion direction. “It was the first time I’d seen Day-Glo clothing. You had very loud rock-and-roll music, which you just didn’t have before in shows. You had boys and girls walking together down the runway, which wasn’t done, and you had Teri Toye, a man who lived as a girl. It was a very powerful moment.” (Ruttenstein says that when Bloomingdale’s started carrying the line, Karl Lagerfeld and Claude Montana always wanted to see Sprouse’s clothes.)

Fall 1984 sequined graffiti dresses

. .

.

.

Debbie harry in Stephen Sprouse, 1988 .

Next Week:

Stephen Sprouse, never made it from Cult Figure to Legend (Part Two)

.

.

info: WikiPedia

http://nymag.com/nymetro/arts by Patricia Morrisroe

love this post. Absolutely well researched and the pics are great as well. I never realised that Stephen Sprouse looked like Steve Strange in his younger pre-blitz days! But better looking and so sexy, just like his clothes. Thnx

I taught Stephen in kindergarten in Columbus, Indiana. He was amazing-wonderful drawing. Lots of boots and capes and terrific clothes on his drawn figures.i always felt he would be famous. He was very quiet and really nice. I was overjoyed years later when one afternoon I turned on my TV and they were featuring his collection of clothes.

Thrilled that I knew him. Miss Babs (Hilger-Hanahan)

The photo of Stephen and

Keith by the motorcycle is not Ms. Toye.

It’s Barbie Steeg she was a model with Elite and a dear friend of Stephen’s.