Contents

- Author’s Note

- Conductors born in the 1850s

- SIR GEORGE HENSCHEL

- ARTHUR NIKISCH

- ROBERT KAJANUS

- MAX FIEDLER

- KARL MUCK

- Conductors born in the 1860s

- ENRIQUE FERNANDEZ ARBOS

- GABRIEL PIERNÉ

- FRANZ SCHALK

- FELIX WEINGARTNER

- RICHARD STRAUSS

- ARTURO TOSCANINI

- LORENZO MOLAJOLI

- MAX VON SCHILLINGS

- HANS PFITZNER

- SIR HENRY J. WOOD

- Conductors born in the 1870s

- LEO BLECH

- OSKAR FRIED

- WILLEM MENGELBERG

- ALEXANDER VON ZEMLINSKY

- SIEGMUND VON HAUSEGGER

- ALFRED HERTZ

- FREDERICK STOCK

- SERGEI RACHMANINOFF

- SIR LANDON RONALD

- SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY

- SELMAR MEYROWITZ

- PIERRE MONTEUX

- ETTORE PANIZZA

- PABLO CASALS

- BRUNO WALTER

- ARTUR BODANZKY

- OSSIP GABRILOWITSCH

- TULLIO SERAFIN

- SIR THOMAS BEECHAM

- PHILIPPE GAUBERT

- SIR HAMILTON HARTY

- GAETANO MEROLA

- FRANTISEK STUPKA

- Conductors born in the 1880s

- D. E. INGHELBRECHT

- CARL SCHURICHT

- BRUNO SEIDLER-WINKLER

- ALBERT COATES

- LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI

- IGOR STRAVINSKY

- HERMANN ABENDROTH

- ERNEST ANSERMET

- NIKOLAI MALKO

- FRITZ STIEDRY

- VACLAV TALICH

- SAMUIL SAMOSUD

- ALBERT WOLFF

- VITTORIO GUI

- OTTO KLEMPERER

- HANS WEISBACH

- WILHELM FURTWAENGLER

- FRANCO GHIONE

- ROBERT HEGER

- GENNARO PAPI

- PAUL PARAY

- GEORGE GEORGESCU

- PIERO COPPOLA

- HANS KNAPPERTSBUSCH

- FRITZ REINER

- SIR ADRIAN BOULT

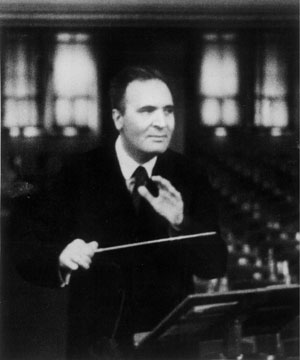

BRUNO WALTER

1876-1962

If Pierre Monteux claims Rhythm, as practiced for instance at the Folies Bergères, as one of his greatest teachers, Bruno Walter lays at the door of his growing-up a large mat lettered SONG. When Walter was a small child, he recalls in Theme and Variations, his father carried him about the house humming into a nearby ear arias from Figaro, Fidelio and other perennial Berlin attractions. And when Walter was a teenager he spent most of his pocket money on operatic performances, reveling in the world of singing, registering of course the intensity of dramatic situations but especially gathering in vibrations that would lead him to write, many years later, “we must concede to lyricism a virtual state of ubiquity in the realm of music.” It would be rash to suggest that Monteux had no ear for a songful line, or Walter no interest in can-cans (my, how he did the Rosenkavalier waltzes!) but Walter did as he took up conducting enthrone a vocal quality as Muse No. 1. This of course leading some commentators to dismiss him as flabby while Toscanini, naturally, was unbending in the face of lyricism, that courtesan of the page. Rubbish! Walter could be as crisp as he chose.

If Pierre Monteux claims Rhythm, as practiced for instance at the Folies Bergères, as one of his greatest teachers, Bruno Walter lays at the door of his growing-up a large mat lettered SONG. When Walter was a small child, he recalls in Theme and Variations, his father carried him about the house humming into a nearby ear arias from Figaro, Fidelio and other perennial Berlin attractions. And when Walter was a teenager he spent most of his pocket money on operatic performances, reveling in the world of singing, registering of course the intensity of dramatic situations but especially gathering in vibrations that would lead him to write, many years later, “we must concede to lyricism a virtual state of ubiquity in the realm of music.” It would be rash to suggest that Monteux had no ear for a songful line, or Walter no interest in can-cans (my, how he did the Rosenkavalier waltzes!) but Walter did as he took up conducting enthrone a vocal quality as Muse No. 1. This of course leading some commentators to dismiss him as flabby while Toscanini, naturally, was unbending in the face of lyricism, that courtesan of the page. Rubbish! Walter could be as crisp as he chose.

As much a guiding principle for Walter as the song thing was a taste for a subtle asymmetry of phrase he doubtless embraced because it enhanced spontaneity. So a Walter performance could encompass a colloquial cornucopia of phraseological softenings and hardenings along the way, vivacities and fragilities, melodious indentations, assorted breezes, enlarged en passants, as if the music were moving through different angles of light. We’re talking a sudden little dip-and-crescendo not specified in the score, a luftpause or silent upbeat contributed in the same spirit, a shift for an ecstatic moment to a head tone from the violins, perhaps, or a pair of oboes – there’s SONG for you. And perhaps an echo of Casals? And in all of this interpretive largesse breathed the Walter an Igor Stravinsky in generous form found “animated, warm, almost laboriously gentle.” Myself, as a member of the populous bass section of the Stanford University Chorus – we were doing Mahler’s Second under Walter with the San Francisco Symphony – I remember how he mesmerized us saying of the choral opening in the last movement, politely but in no uncertain terms: “the sound must be as on a distant horizon . . .”

And a footnote to say that the sternest thing Walter would say in a rehearsal, addressed to an orchestra frequently identified as “my friends,” was: “I am not happy.”

A number of American orchestral musicians have said the beat Walter used to summon his song-and-so-forth-and-so-on was difficult to decipher, at least at first. But in the words of the conductor Georg Solti, quoted in Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky’s thoughtful biography of Walter, he “had a strange, not very clear beat, but he was proof that the beat is not an essential part of a conductor.” Ah, there’s the quest for ASYMMETRY in action, the beat might just benefit from not being blueprint-clear. And Nikolaus Harnoncourt, the distinguished conductor and early-music pioneer, remembered no problem whatsoever following Walter from his seat among the cellos of the Vienna Symphony early in his career. As for those lowly Stanford Chorus basses, I seem to remember them coming in on cue.

Sometimes the phraseological inventory of a Walter performance came close to bursting, but generally to the performance’s advantage. Quickly comes to mind his broadcast of Mozart’s Prague Symphony with the Orchestre National in Paris 5-5-55: the harrumphy forte flourishes in bars 1 and 2 of the adagio introduction are absolutely curt but bars 4 and 5 bring a tempo lengthened and increasingly so – the scene has quickly become nostalgia-packed – to highlight the sighs in Mozart’s woodwind (forte) then strings (piano). End of bar 6 and I’ve penciled in my score “a vocally passionate entrance” of those first violins legato-ing down four sixteenths to a long note in a, yes, Casalsian way. After the introduction of this performance closes with the nursery rock of thirty-second notes over an expectant bass the allegro comes on with maximum zest in its initial throbbings, only to have the tempo conclusively brought down, let’s say eight beats-to-the-minute, by the fifteenth bar, that’s measure 51, the point at which the first violins skip out of their accompanimental wrap with a fresh theme, staccati descending to a sigh.

No less important in Walter’s gramophonic oeuvre is the Strauss Don Juan he conducted with Berlin’s Philharmonic on his return to that city, from which he’d long been exiled, in 1950 — in, I should add, a spirit of reconciliation which was pure Walter. Taut yet relaxed is this performance, and it’s especially wonderful in that great central scene featuring an autumnal, hermitic oboe – remember, a few pages back, San Francisco’s Merrill Remington in his enchanting collaboration with Pierre Monteux. Strauss prescribes 76 beats to the minute for this scene, but the notational condiments served up with this “76” – dolce, con espressione, ma tranquillo – suggest that deviations numerically downward would not be amiss. And so it is that Walter begins at what might be called “60-ish and lingering,” he’s no faster than 52 when the clarinet has the limelight, and, with Letter N and the benedictory dolce espressivo of flutes and violins reaching, it seems, into some desert sky of infinite peace, here with pacing even a little slower, and a very soft touch, he creates an Abschied Mahlerish in its extended dolce made in heaven. Absolutely unique!

And also in this Don Juan: the startlingly soft-textured pianissimo of the cushiony chords and measured baritonal oscillations just prior to the announcement of the first love theme, nine measures after Letter D. Walter the master of seductive detail within a purposeful agenda is at work.

“Bruno Walter” was born Bruno Schlesinger. Deeming appropriate a certain de-syllabization in the cause of a nom de baton — or perhaps one should say a nom de main because in the passages he felt required head tone he tended to lend his stick to a clenched left hand, this freeing the right for lyrical phrase-molding — young Schlesinger looked no further, so goes the perhaps apocryphal story, than the minstrel in Die Meistersinger whose full name was Walther von Stolzing. But it was a Gustav, Mahler by name, who was Walter’s mentor early on. The fledgling conductor worked a number of seasons under him in Vienna, becoming fully at home, if he wasn’t already, with the delightful tricks so to speak of that city’s phraseological trade, its frequently laidback but rarely sloppy musicmaking. From 1912-22 Walter was general music director at the Munich Opera, positions following in Berlin, Leipzig, Amsterdam and Vienna along with much guesting in London, Paris and New York. Fleeing the Nazis, he settled in tropical Beverly Hills, returning East for numerous performances with the New York Philharmonic and at the Metropolitan Opera. His Met Verdi became as well known as his trademark Mozart and Fidelio: has anyone provided a more civilized accompanimental trot beneath the baritone’s Alla Vita in Ballo in Maschera, or such grimly tenacious chords at the opening of La Forza del Destino?

Walter must have become very familiar with the austere beauties of half-barren landscapes along the Colorado/New Mexico/Arizona route of the Santa Fe Super Chief, that Extra Fare hideaway on wheels. Presumably in one of its comfortable compartments after a pancake breakfast a doubtless bow tied and herringbone jacketed Walter worked not only on his scores but his autobiography, while Mrs. Monteux, back in Maine, prepared to “do” Pierre. She, of course, was Monteux’ third wife and he called her the Eroica. Walter’s Theme and Variations is an engaging book, I’ve read it two or three times over the years, and he wrote another one, Of Music and Music Making, which is chock full of good sense. Let’s have a flag stop on our journey and drink in some of its battlefield observations on interpretation: I have a little list of them, they’re what Maitre Monteux in his conducting school in Maine would have called “must remembers”:

ONE: “Drastic tempo changes that dispel continuity musn’t always be considered as sins committed by hardened sinners . . . Often this sin is committed from the conviction that a change of speed is the only way in which to express the deeply-felt meaning of some passages.” . . . . TWO: “The measurability of musical rhythm, and therefore the acurateness of its notation, is only approximate. One’s inborn feeling for rhythm is not concerned with numerical exactness in the relation of long to short, or short to long, as laid down by notation; it deviates from it, favoring instead an inner impulse which is compelled, instinctively, by a higher, immediate, non-arithmetical insight into the rhythmical meaning of each group of notes.” . . . . THREE: “The composer, to be sure, tries his best to make us find the right tempo by his indications. But not even the apparently incontrovertible tempo indication by means of metronome numbers can give us a reliable idea of the speed. A marking such as half = 92 gives us a speed that may be right for the first few bars, but must needs lose its validity as soon as a change in expression demands a modification of speed.” . . . . FOUR: “If I have to conduct three performances of Bach’s B minor Mass on three successive evenings, it is bound to happen that, without change in my intentions, I shall conduct the same passages at slightly varying speeds, and all three might be correct.”

Good stuff – and thanks be for inner impulses. And I’m reminded of Monteux’ wisdom from his pastoral pulpit at Hancock — he had for his students eight Musts and twelve Don’ts. I’m especially fond of Must No. 2 from this unsvelte maestro: “Never bend, even for a pianissimo. The effect is too obvious behind.” And now if we add to the Super Chief the Queen Mary, Normandie, Orient Express, Night Ferry and a few other First Class accommodations to the list we can follow Walter on assorted international shuttlings pre-, mid- and post-war, catching a number of performances from the last quarter century or so of his magnificent career. In the process you’ll notice that Walter could be crisp in “Old Europe” Salzburg and gemeutlich in the aluminum alleys of Deco New York, so beware of generalizations that his conducting was tailored to a milieu . . .

“Live” at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, 3-15-36: Wagner’s Flying Dutchman overture – A supple, howling introduction, a probing, long-lined lyric interlude, a spontaneous and absolutely furioso allegro con brio, a grandly rhetorical close: Walter extracts all the spray and splash from Wagner’s tone poem of an overture . . . “Live” at the Salzburg Festival, summer of ’37: Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro with Pinza, Novotna, etc. – A famous Walter performance, drama-savvy and never nailed into conventionality: the music arrives with an almost childlike charm, but the dead-serious aspects of the story are scarcely skimped. Figaro’s Se vuol ballare is swept by the winds of anger, Bartolo’s La Vendetta is amusingly melodramatic, the Susanna-Marcellina duet runs on tiptoes of seething suspicion, Figaro’s Non più andrai begins at a spacious, rather musing tempo but snaps, or is kicked, into a much brisker speed when the music becomes seriously military — poor Cherubino’s minutes as a civilian are surely numbered!

“Live” at the NBC Symphony, New York, 3-11-39: Mozart’s D minor Piano Concerto featuring Walter himself as soloist – With its trembling warmth and confiding in you, not-quite-symmetrical phrasing (and dig those delightfully crazy modern cadenzas) this is perhaps the ideal introduction to Walter the beloved musician in action

. . . And one week later in ’39: a Brahms First Symphony with much ammunition to shush critics of Walter as a slack and overly romantic interpreter, in fact it seems to smack of fury at the world situation with Czechoslovakia in its death throes across the Atlantic. The first movement allegro is pulsing and almost hectic at the start, then with the pregnant pages of the famously lyric second subject Walter’s listeners sitting by their bronze Philcos must surely have been drenched in sadness. Another Saturday evening thrill was the positively demonic delivery of this movement’s snappy closing theme. Hell’s Alley at 8-H!

And the following year at NBC, Ravel’s Rhapsodie Espagnole (2-24-40) in a fluid, atmospheric performance with the calculated blaséness which is absolutely apropos. Remember that in “live” performances Walter was free to perform the French repertoire which hard-boiled type casting generally withheld from him on commercial discs. Another example: his steamy La Mer of Debussy with the New York Philharmonic in 1941. The deep longing in the finale tugs at one’s soul. Walter did score an end run around linear recording executives when he managed to record commercially, and very nicely too, Samuel Barber’s single movement First Symphony — and Pierre Monteux, at least in concert, was equally persuasive in Barber-colleague Paul Creston’s Second.

“Live at NBC, 3-2-40: Schumann’s Fourth – Exciting! The tension-rich introduction sounds as if it’s scaling some symphonic height, the lebhaft that follows (lively, that is) is crisp and impassioned, with spitting string sforzandi after the double bar and wonderfully bright and sometimes baleful brass. The romanze is stiff-lipped/wistful, bolder and a tad brisker than the sweet dirge Frederick Stock serves up in his grazioso recording from Chicago ’41. The scherzo has a swing-your-partner feel, maybe the result of breakfasting with Stetson-hatted characters on the Santa Fe Railroad . . . “Live” at NBC, 3-9-40: Tchaikovsky’s Fifth – Unlikely repertoire again, to judge by Walter’s formal discography, but this is a very strong performance, capped by a finale in which the daringly broad tempo for the torso of the movement serves as a giant and majestic upbeat to the molto maestoso near its conclusion . . . And “Live” at the Hollywood Bowl, 7-16-42: Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet – An artful performance in which the introduction seems to be pulled toward the ensuing allegro giusto, then the lolling lovers in the great lyric scene are given their full due, the solo horn like a cat in heat.

“Live” at the Met, 1-15-44: Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera — Spaciously paced to enhance majesty and tension, this is a great Saturday afternoon’s entertainment. The performance is charged with life from bar 1, boasts a symphonic sound from an orchestra Walter evidently was not wild about, is filled with compassion, urgency, finesse: the cup of praise runneth over. Not surprising from this conductor who grew up on opera as a substitute for the not-yet-available radio melodrama is the utter desperation igniting the lovers’ duet in act 2, also the ominous drag in the tempo as the empowered conspirators ho-ho-ho their way to the conclusion of this scene. Amazing how Walter’s Verdi style is echoed in the conducting of Nicola Luisotti in 2009! Both, in short, are “conducting the story” . . . And “Live” at the Boston Symphony, 1-21-47: Haydn’s Symphony No. 92 — Aha, Walter has in a brief visit changed the Boston’s wonderful violins into Viennese creatures, playing with a mellow vibrance suggesting the Philharmoniker across the pond. It’s rather as if you put sherry in the pot of baked beans. The most fascinating detail in this gemuetlich performance occurs in the leadup to and achievement of the second subject in the opening allegro. With a couple of passing retards on the approach Walter creates a little symphonic smokescreen of complexity, from which emerges, with an exquisite hesitation constructed out of delicate restraints in tempo and dynamics, music that seems to dwell in a totally new dimension.

“Live” in Munich with the Bavarian State Opera Orchestra, 1950: Weber’s Euryanthe overture — Swingy, weighty, impetuous, this romp has a characteristic Walterian dash. In his brisk take on the night music interlude midway in this endearing chestnut the light at the end of the lyric tunnel is never in doubt . . . “Live” at the Stockholm Philharmonic, 1950: Schubert’s C Major Symphony – Full of charm! Interesting how as the theme of the introduction is sucked toward the coming allegro ma non troppo the strings playing servant to thematical winds have in this performance a clearer profile than in Walter’s amazingly ordinary commercial recording with the London Symphony from 1938 — and the autumnal Columbia Symphony version from his last years in southern California as well – the result being a delightful situation in which the violins, as if very talkative Downstairs people, seem to be commenting, favorably one hopes, on those Upstairs woodwinds. Incidentally, Ryding and Pechefsky are nail-on-head when they write of Walter’s final Columbia Symphony (aka L.A. Philharmonic) recordings as glowing “with their own ripe and sensuous luster.” This is pipe-and-slippers musicmaking. There’s no audience and it’s as if Walter were sitting back, taking his time, almost watching himself meticulously but effortlessly conjuring that glow on his wondrous acoustic canvas.

“Live” at RAI, Rome, 4-16-52: Brahms’ German Requiem, in Italian, with Carteri and Christoff – And Walter injects Viennese vibrance into Roman strings too. A singing people of course, the Italians, and Walter who was forever exhorting his orchestras to “zing!” sounds pleased as this mellow performance proceeds, a Requiem Tedesco floating on clouds to do Tiepolo proud . . . “Live” at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, 6-6-52: Mahler’s Fourth Symphony – A revelation of charm, pathos and transparency, unfolding in gentle meanders that keep the music far from a freeway mentality: Walter could have taught an Upper Division course at USC in “How to Make Music Go Sideways.” . . . and “Live” on the Standard Hour with the San Francisco Symphony, 4-18-54: Wagner, Parsifal prelude, act 1 – One of the better trances chronicled in this volume, this performance boasting a lot of hummy head tone sounds as if it were played under the influence of nothing less than hypnosis. It is almost on a distant horizon!

“Live” with the Symphony of the Air (ex-NBC), New York, 2-3-57: Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony – This was the climax of a Toscanini Memorial concert in which Monteux and Charles Munch also participated. Warm cellos and compassionate violins signal a tragic element at the outset, and with a distinctly intimate approach to the opening movement’s second subject the marcia funebre seems virtually begun. The marcia itself brings a heady phraseological mix of the vibrant, the caring, the debonair, weltschmerz not excluded. Unrestrainedly gruff moments are punctuations of reality on this Elysian scene. Gruff by the way is something Walter could do very well: see for instance the ultra-determined whackery of his L.A. Philharmonic timpanist dealing, “live” in ‘47, with crescendi in the last scene of the opening movement of Brahms’ First. Crescendi which, in the black and white of Brahms’ score, are of maddeningly indeterminate size. Of course the most impetuous of timpani aficionados was the highly imaginative Charles Munch whose elegance, thanks be, outran his rambunctiousness.

And “Live” at the Chicago Symphony, 3-13-58: Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony – Simplicity reigns in a direct and almost Mozartian first movement, rather more allegro con spirito than Schubert’s allegro moderato, the development suggesting son of the Don Giovanni overture opening. The succeeding andante con moto is slower without a doubt than the composer’s indication, Walter’s adagio fending off the tendency of Schubert’s “twin” movements to run together tempo-wise like beef stew and creamed potatoes on a not flat plate. The second theme is absolutely lost in the stars way above Lake Michigan where the night flights to San Francisco float and bump at 39,000 feet and sometimes the music seems to be almost holding its breath as its pilot basks thankfully in the enjoyment of its beauties. An adagio, this, that becomes in its prevailing poignancy a farewell symphony of sorts . . . What else can I tell you? That the recapitulation of the second theme in the slow movement of Brahms’ Fourth poured like the best maple syrup in Walter’s fond hands, adagio for sure. And that Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde was one of his fondest signature pieces. He couldn’t persuade the Met to let him conduct it, but listen to the Prelude with the New York Philharmonic 5-14-44. A different kind of farewell here: in this soulful, distressed and not un-angry performance in which the music seems to weep unashamedly onto a laundry-ready sleeve the lovers are destined not for the certain coitus Fritz Reiner so oblingingly provides but a great medieval cliff to jump from, achieving their ineffable eternity thereby.

Now a punch line: asking his L.A. bassoon (“my dear”) for a staccato entrance in the slow movement of Beethoven’s Fourth, Walter advised him, re the shorter notes in his dum, d-dum, d-dum, “better to be too late than too early.” Yes, added Walter, one of Beethoven’s trickiest movements!